Document Text |

Summary |

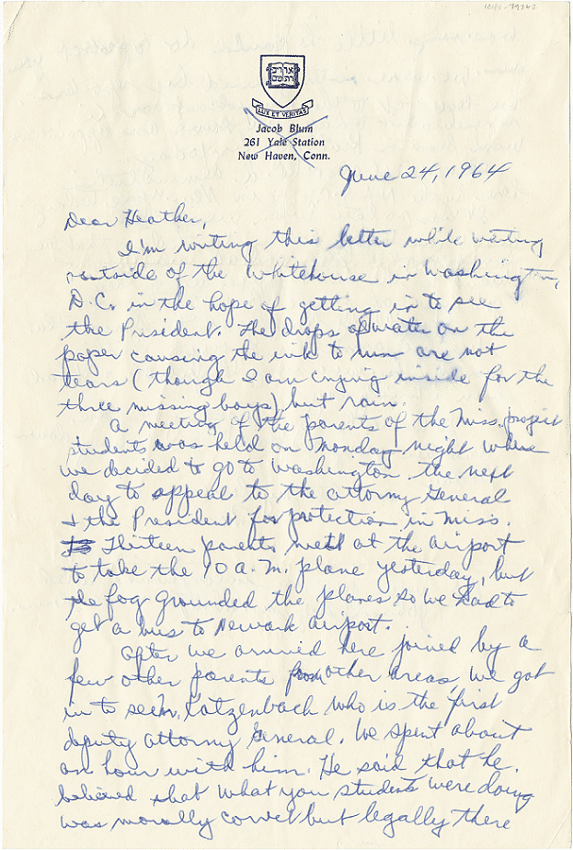

| June 24, 1964

Dear Heather, |

This is a letter to Heather Tobis Booth. It was written on June 24, 1964. |

| I’m writing this letter while waiting outside of the White House in Washington, D.C. in the hope of getting in to see the President. The drops of water on the paper causing the ink to run are not tears (though I am crying inside for the three missing boys), but rain. | I am writing this letter while I am sitting in the rain outside the White House. I am sad about the three boys in Mississippi who are missing. |

| A meeting of the parents of the Miss[issippi] Project students was held on Monday night where we decided to go to Washington the next day to appeal to the Attorney General and the President for protection in Miss[issippi]. Thirteen parents met at the airport to take the 10 a.m. plane yesterday, but the fog grounded the planes so we had to get a bus to Newark Airport. | The parents of students in the Mississippi project decided to go to Washington, D.C. to meet with the Attorney General and the President to ask for protection for the students. |

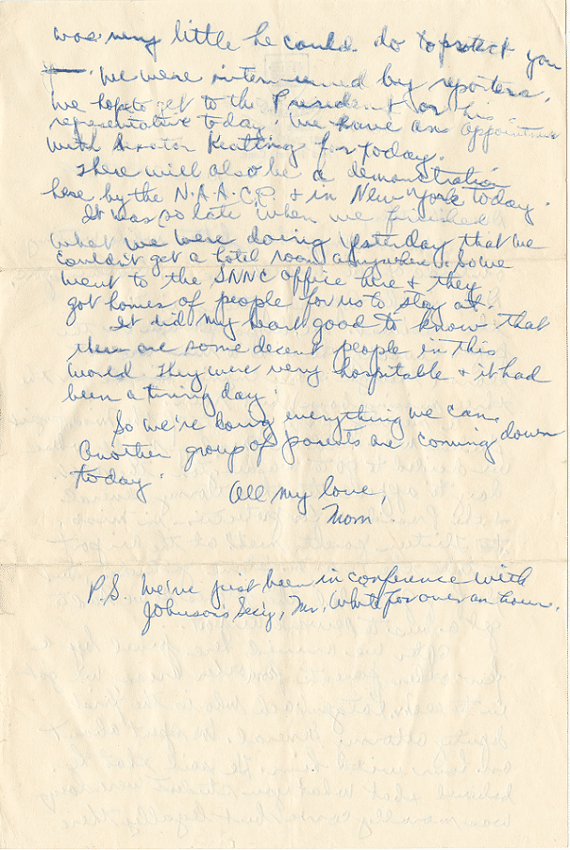

| After we arrived here joined by a few other parents from other areas, we got in to see Katzenbach, who is the first deputy attorney General. We spent about an hour with him. He said that he believed that what you students were doing was morally correct, but legally there was very little he could do to protect you. We were interviewed by reporters. We hope to get to the President or his representative today. We have an appointment with Senator Keating for today. | We (the parents) met with the Deputy Attorney General for an hour. He supported the students, but said he could not do much to help. We spoke to reporters. We have an appointment to meet with a Senator today. |

| There will also be a demonstration here by the N.A.A.C.P. and in New York today.

It was so late when we finished what we were doing yesterday that we couldn’t get a hotel room anywhere. So we went to the SNCC office here and they got homes of people for us to stay at. |

The NAACP is protesting in Washington, D.C. and New York. We could not get a hotel last night, so we stayed at the home of a SNCC member. |

| It did my heart good to know that there are some decent people in this world. They were very hospitable and it has been a tiring day. | I am happy to know there are still good people. They were very nice to us. |

| So we’re doing everything we can. Another group of parents are coming down today. |

We are doing everything we can. More parents are coming to help. |

| All my love, Mom |

All my love, Mom (Hazel Tobis) |

| P.S. We’ve just been in conference with Johnson’s Sec’y, Mr. White, for over an hour. |

After signing this letter, we met with President Johnson’s advisor for an hour. |

“Letter from Hazel Tobis to Heather Tobis during Freedom Summer”, 1964. Midwest Academy Records, Research Center, Chicago History Museum.

Background

In 1964, a group of Black civil rights organizations led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) launched Freedom Summer. The public goal was to register thousands of Black voters in Mississippi. The private goal was to gain stronger national support for the civil rights movement.

Hundreds of mostly white college students from the North volunteered for Freedom Summer. SNCC’s leadership wanted all Americans to understand the harsh reality of Black life in the South. They hoped these eager volunteers would witness this reality and return home with a new purpose. If the federal government was tired of hearing from Black activists, perhaps it would listen to young, white, educated voters.

SNCC achieved national attention in a tragic way. Early in the summer, three participants disappeared. Their names were James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. Six weeks later, their bodies were discovered. They had been brutally lynched by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were white college students from New York. SNCC leaders never intended to make white volunteers martyrs. However, their theory that the American public cared more about white activists was true. Extreme violence against Black civil rights activists was an almost daily occurrence in Mississippi. But the disappearance of white college students made national news. The media coverage of the incident motivated more people to become involved in the movement and placed pressure on the federal government. Less than one year later, the Voting Rights Act was signed into law.

About the Document

Heather Tobis Booth was a politically active student at the University of Chicago. In the summer of 1964, she volunteered for Freedom Summer. While in Mississippi, she worked in a Freedom School and helped to register voters. That experience led her to pursue a career in civil rights organizing. In 2000, she was the founding director of the NAACP National Voter Fund.

Heather received this letter from her mother, Hazel Tobis, shortly after arriving in Mississippi. Prior to this letter, Heather’s parents tried to convince her not to go. The letter describes how a group of parents lobbied in Washington, D.C. to protect their children, who were Freedom Summer volunteers. The reference to the “missing boys” suggests that they were motivated by the disappearance of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner.

Vocabulary

- Attorney General: The chief legal officer of the United States, who gives legal advice to the president and the federal government.

- Ku Klux Klan (KKK): A national organization that promoted an America made up entirely of white, Protestant, native-born Americans and was inspired by the KKK of the 1870s, a secret organization focused on terrorizing black citizens in the post-Civil War South.

- lynching: The illegal execution of a person by a mob.

- martyr: A person who suffers or dies for a cause.

- Mr. White: Lee Calvin White, an advisor to presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): A civil rights organization that was founded in 1909 to fight racial discrimination and still exists today.

- Senator Kenneth Keating: A long-term Republican Senator from New York who supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC): A national organization founded to recruit and organize young people interested in the civil rights movement.

Discussion Questions

- Why is Hazel Tobis in Washington, D.C.? Who is she traveling with, and what do they hope to accomplish?

- Why are Hazel and other parents concerned for their children?

- What kinds of reactions do the parents receive while in Washington, D.C.?

- What does this letter tell you about the parents of white civil rights activists?

- After reading the background information and letter, what do you think of SNCC’s strategy to recruit white volunteers from the North?

- How do you think Heather felt receiving this letter?

- Most Freedom Summer volunteers, including Heather, chose to stay in Mississippi after the disappearance of the three young men. What does this tell you about Heather and the other participants?

Suggested Activities

- Civil Rights activist Ella Baker was one of the primary visionaries and leaders behind Freedom Summer. Pair this letter with her life story to learn more about the push for equal rights in 1964.

- The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony on behalf of the party grew out of Freedom Summer. Pair Fannie Lou’s testimony with this letter and think about the differences between white Northern and Black Southern activists working in Mississippi in 1964. (Heather also met Fannie Lou Hamer during her time Mississippi. See an image here!)

Pair this letter with the life story of Mamie Till-Mobley and ask students to think about the different public reactions to these different lynchings.

Connect this document to other resources in this unit that explore women’s roles in the Black civil rights movement, including the life stories of Ella Baker, Dorothy Bolden, Mary Church Terrell, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mamie Till-Mobley, and Pauli Murray, as well as the Little Rock Nine document, the Loving v. Virginia document, and Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE