This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

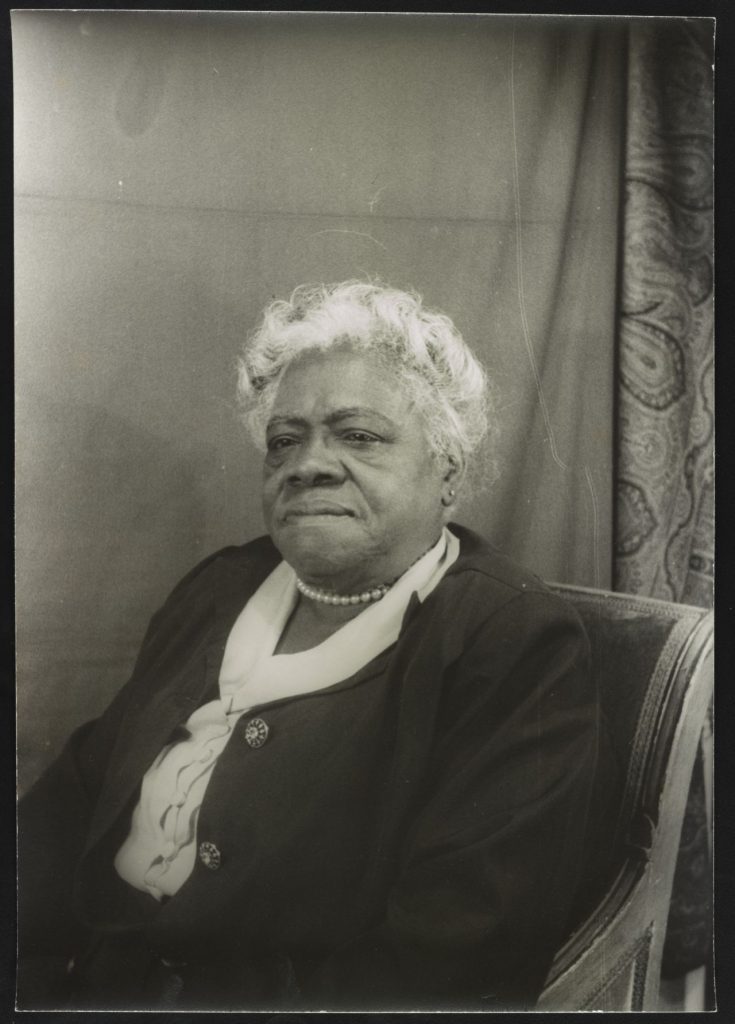

Mary McLeod Bethune was born on July 10, 1875 in Mayesville, South Carolina. She was one of seventeen children. Her parents and some of her older siblings had been enslaved before the Civil War. Mary spent much of her childhood balancing school and work in cotton fields. In 1888, she earned a scholarship to Scotia Seminary in North Carolina. After graduation in 1893, she continued her studies with the goal of completing missionary work in Africa. However, most churches sent only white missionaries abroad, so Mary became a teacher instead.

While teaching, Mary met fellow teacher Albertus Bethune. Mary and Albertus married in 1898 and had a son named Albert in 1899. Shortly after Albert’s birth, the family moved to Daytona, Florida. Although the Ku Klux Klan had a chapter in Daytona, many Black families moved to the area in search of jobs.

Mary saw an opportunity in this growing community. She knew that education was one of the few ways Black citizens, especially Black women, could break the cycle of poverty and dependence on racist systems when they were still denied voting rights and economic opportunities. There were very few schools for Black girls in the area, so Mary founded one.

On October 3, 1904, Mary opened the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute with only five students. The school focused on practical, employable skills, including domestic science, sewing, agriculture, and teaching. Within two years, she had 250 students, many of whom lived in the school’s dormitories.

In 1907, Albertus left Mary. Although they would officially stay married until his death in 1918, Mary had to raise their son and manage her growing school alone.

Mary did not allow personal challenges to jeopardize her school. She worked tirelessly to keep the school running. Many of the school’s supplies were donated secondhand or picked up by Mary at the local landfill. Mary had so little money that she wore secondhand clothing mended by her students in sewing class. Her hard work attracted the attention of both white and Black philanthropists who vacationed in Florida. The school’s board soon counted many of the nation’s most famous businessmen as members, including John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In later years, Black millionaire and businesswoman Madam C.J. Walker was a donor.

The school adapted to the community’s changing needs. Mary added a high school and vocational programs. In 1911, she realized that none of the local hospitals served Black patients. In response, she added a nursing program so that the school could open its own hospital.

By 1923, Black education in Florida was changing. With more public schools opening, Mary shifted her focus to helping young women after high school. She merged her school with the older Cookman Institute for Men in Jacksonville. The new coed school was named Cookman-Bethune College. Mary served as the president of the school from its formation until 1942. By 1941, the school was a four-year college on a thirty-two-acre campus with fourteen buildings and 600 students.

Mary saw education as one way to fight against the injustices of racism in the United States. But she knew that teaching was not the only answer. Mary was active in anti-lynching and desegregation campaigns. During World War I, while her son served in the Army, she pressured the Red Cross to integrate its services. In 1924, she was elected president of the National Association of Colored Women. In 1935, she founded the National Council of Negro Women, for which she served as president from 1935 to 1949. She was also vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1940 to 1955.

People in the government noticed Mary. She participated in special commissions under President Calvin Coolidge and President Herbert Hoover. Through this work, she met First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Eleanor and Mary believed it was possible to improve the status of women and people of color in America. Eleanor encouraged her husband, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, to give Mary a leadership role in the New Deal. In 1934, Mary became director of the Division of Negro Affairs for the National Youth Administration (NYA), and with it, the highest-ranking Black woman in the federal government to date. Mary fought for integrated state advisory boards, better skills training for youth, and more Black staff and managers within the NYA. The NYA was the first federal agency to aid Black youth through educational and vocational training projects.

Mary was also part of a small group that advised President Roosevelt on policies relating to Black citizens. This group was known as FDR’s “Black Cabinet.”

For I am my mother’s daughter, and the drums of Africa still beat in my heart. They will not let me rest while there is a single Negro boy or girl without a chance to prove his worth.

Mary used her high-profile position in different ways to fight for racial equality and dignity. In 1938, Mary attended the Southern Conference on Human Welfare. When the session leader referred to her as “Mary,” she insisted on being publicly recognized as “Mrs. Bethune.” One onlooker noted that a Black woman insisting on the title “Mrs.” was a big political statement in the deeply segregated South. Closer to home, Mary participated in a 1939 picket line in Washington, D.C., when a local drugstore refused to hire Black employees.

When the United States joined World War II, Mary contributed to the war effort as she continued to focus on equal rights. She worked with A. Phillip Randolph to persuade President Roosevelt to establish a Federal Committee on Fair Employment Practices and desegregate the defense industry. She also served as the assistant director of the Women’s Army Corps during WWII. In that role, she advocated for Black women in the armed forces.

Mary’s relationship with the Roosevelts was so close that Eleanor gave Mary one of her husband’s canes after his death. Mary enjoyed collecting canes and often walked with one, although she had no physical need for it. She believed carrying a cane gave her “swank” and earned respect.

After World War II, President Truman appointed Mary as a delegate to the San Francisco Conference, where the United Nations was formed. She retired to Florida in the late 1940s.

Shortly before her death, Mary wrote a “Last Will and Testament,” which outlined her philosophy. In it, she emphasized the importance of love, hope, education, racial dignity, and support for future generations.

Mary died on May 18, 1955 of a heart attack. In 1974, a monument in her honor was unveiled to a crowd of 18,000 people. It was the first statue on public land in Washington, D.C., to honor a Black woman. It includes a depiction of Mary handing her legacy to future generations.

Vocabulary

- Eleanor Roosevelt: The first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945. She was also a civil rights activist and delegate to the United Stations.

- John D. Rockefeller, Jr.: An American businessman and philanthropist. The son of the founder of Standard Oil, John D. Rockefeller.

- Ku Klux Klan: A white supremacy group formed by ex-Confederates after the Civil War that terrorized Black citizens and their supporters.

- Madam C.J. Walker: The founder of a hair product company for Black women and the first self-made Black female millionaire.

- missionary: A person sent to spread religion to new communities, particularly in other countries.

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): A civil rights organization that was founded in 1909 and still exists today.

- National Youth Administration: A New Deal agency that focused on providing work and education opportunities for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25.

- New Deal: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s national program for stimulating the American economy during the Great Depression. Included employment, housing, and social service support systems.

- Phillip Randolph: An African American leader in the civil rights movement.

- seminary: A school that prepares students to be leaders in religious work.

- vocational: Relating to a specific occupation or type of employment.

- Women’s Army Corps: The women’s division of the United States Army, which was established in 1942.

Discussion Questions

- How did Mary’s childhood and early adulthood shape her career? Why did she choose education as the first focus of her activism?

- What challenges did Mary face in opening her school? How did she overcome these challenges? What does this say about her personality?

- Mary believed it was important to be an activist both for women of all races and for all Black Americans regardless of gender. Why is this distinction important? What does it say about the experiences of Black women?

- How did Mary’s friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt shape her life?

- Examine the photograph of Mary’s memorial in Washington, D.C. What do you see? What does it say about Mary’s career and ideals?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 7.9: The Great Depression

- Lesson Plan: In this lesson designed for eleventh grade, students will learn about Mary McLeod Bethune and her fight for racial equality.

- Mary was part of a vast network of women involved in New Deal policies and work. Compare her life story with those of Dorothea Lange and Ellen Woodward.

- Mary’s life was very similar to that of Mary Church Terrell. Compare their life stories and consider how each woman fought for the rights of African Americans.

- Mary was not the only woman of color to struggle with the balance of women’s rights and Black rights. Combine this life story with that of Pauli Murray, who coined the term “Jane Crow.”

- Mary had a successful career as an educator in the Progressive Era before her work during the Great Depression. Combine her story with resources from Modernizing America, 1889–1920.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE