This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Malintzin was born around the year 1500, the eldest child of Nahua nobility. She grew up in a region of the Yucatán Peninsula where the Mayan and Aztec Empires both had influence, though neither had complete control. Her parents named her Malinalli, after the goddess of grass. Malintzin must have been an outspoken child, because when she was still young her family added Tenepal to her name, which means “one who speaks with liveliness.” When she was eight or nine years old, Malintzin was enslaved. It is not known whether she was sold by her family or kidnapped, because every historical text about her life tells the story differently. But it is certain that she was enslaved at a young age and forced to move away from her childhood home.

As an enslaved girl, Malintzin had no control over the work she was made to do. She labored in the homes of those who enslaved her, cooking, cleaning, and performing any other domestic task she was assigned. She may have been forced to perform sex work. Malintzin was sold several times during the early years of her enslavement and traveled around the Yucatán Peninsula. During her travels, she became fluent in both Yucatec and Nahuatl, the languages of the Mayan and Aztec people. Malintzin also spoke high Nahuatl, the language of the courts, which supports her claim to noble birth.

In 1519 Malintzin’s life was forever changed by the arrival of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. When he arrived at the city of Pontonchán, the city leaders gave him twenty enslaved women as a peace offering. Malintzin was one of the women given to Hernán. The enslaved women were baptized by Catholic priests, and each was given the European name Marina. Hernán gave Malintzin to one of the noblemen who served under him.

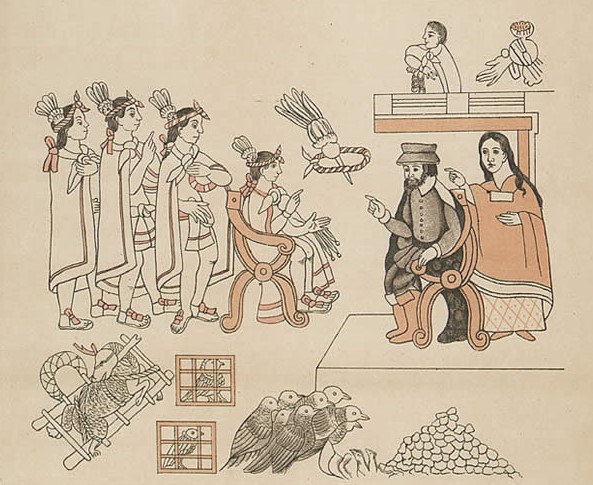

Hernán had come to the area with the intention of conquering the Aztec Empire. It was not long before he realized that Malintzin was fluent in the two major languages of the Yucatán Peninsula. This was a valuable skill, so Hernán took her back into his custody. He needed her language skills to speak with the various Indigenous leaders he would encounter during his conquest. At first, Malintzin was paired with a Spanish priest who could speak Yucatec, but she quickly learned Spanish, becoming Hernán’s only interpreter.During Hernán’s conquest of the Aztec Empire, Malintzin served at his right hand. In recognition of her position within Hernán’s forces, his followers began to address her with the title Doña, an honorific meaning “lady” that was not usually used for enslaved women. It was at this time that the Aztec community began calling her Malintzin, a combination of her birth name and a Nahuatl honorific. She was so important in negotiations between the two groups that “Malintzin” became the word used to refer to Hernán as well. Moctezuma, the ruler of the Aztecs, addressed all of his official correspondence with the Spanish to her. She appears in every illustration of Hernán meeting with Indigenous leaders and nobility and is sometimes even shown negotiating with leaders on her own. With Malintzin’s help and guidance, Hernán was able to make alliances with communities who were tired of Aztec rule. She uncovered plots to betray the Spanish, giving Hernán time to stop them before their enemies did any serious damage. She participated in all of the major events of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, through the fall of Tenochtitlán in 1521. Her work was so vital that Hernán himself once remarked that, next to God, Malintzin was the most important factor in his success.

Throughout the conquest, no matter how much power she seemed to have, Malintzin was enslaved.

With Malintzin’s help, Hernán was able to kill Moctezuma and end the rule of the Aztec Empire, ushering in a new era of Spanish domination. Some view Malintzin as a woman who single-handedly brought about the doom of her people to advance her own interests. In modern Mexican culture, her nickname, La Malinche, has become synonymous with deceit and betrayal. But this interpretation of Malintzin’s actions ignores one key fact: throughout the conquest, no matter how much power she seemed to have, Malintzin was enslaved. She had to serve the interests of her enslaver, or risk death at his hands. She may have had very little affection for the society that had enslaved and ruthlessly exploited her since childhood. It is impossible to know for certain what Malintzin’s motivations were. She left no written record. But when considering her story, it is important to keep all the circumstances of her life in mind.

After the conquest of Tenochtitlán, Malintzin continued to live and work with Hernán. She bore him a son, Martin, in 1522. It is impossible to know whether this was something she wanted or whether it was forced upon her.

In 1524 Malintzin travelled with Hernán to the area of modern-day Honduras, where she again served as his interpreter while he tried to suppress a rebellion. In the same year, Malintzin married Juan Jaramillo, one of Hernán’s captains. The marriage elevated Malintzin to the status of a free Spanish noblewoman, with all the rights and privileges of that class. Hernán arranged the marriage, and it is probable that he did so to get Malintzin out of his household before his wife arrived in the colony. Her marriage improved her status, but still took place within the confines of the conquest.

Malintzin and Juan had a daughter, Maria, in 1526. Her marriage meant that both of her children became part of the Spanish nobility in Mexico and in Spain. Their prominence as members of the new mixed-race generation earned Malintzin a new honorific: “mother of the mestizo race.”

Malintzin died in 1529 during a smallpox outbreak. She was only about twenty-nine years old. In her short life she became one of the most important figures of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, and she left the world a wealthy, free woman. Historians still debate how her life should be interpreted, but there is no doubt that her actions changed the course of Mexican history.

Vocabulary

- alliance: An agreement between countries or communities to work together.

- Aztec: One of the two dominant communities of the Yucatán Peninsula at the time of European contact. Most Aztec people spoke the Nahuatl language.

- conquistador: The name for the Spanish or Portuguese military leaders who conquered Central and South America in the 1500s.

- Dońa: The title for a Spanish woman of rank.

- honorific: A title given to someone out of respect.

- Maya: One of the two dominant communities of the Yucatán Peninsula at the time of European contact. Most Mayan people spoke the Yucatec language.

- mestizo: A person of mixed Indigenous and European heritage.

- Nahua: Indigenous groups that have lived across Mexico and El Salvador for hundreds of years.

- Nahuatl: The language of the Aztec people.

- smallpox: A deadly disease that caused fever and blisters in those who caught it, and left scars on survivors.

- Tenochtitlán: Capital of the Aztec Empire. Today the ruins of Tenochtitlán are in the Historic Center of Mexico City.

- Yucatán Peninsula: A land mass in Central America that extends into the Gulf of Mexico between the Caribbean Sea and the Bay of Campeche.

- Yucatec: The language of the Mayan people.

Discussion Questions

- What skills and circumstances allowed the enslaved girl Malinalli to become the powerful Malintzin?

- What part did Malintzin play in the conquest of Mexico? Why was she revered by the Spanish?

- Why is Malintzin such a hated figure in Mexican history today? What factors in her life complicate characterizing her as a villain?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 1.4 Columbian Exchange, Spanish Exploration, and Conquest

- Include this life story in any lesson about the conquest of the Aztec Empire. This life story highlights the important role a woman played during the conquest.

- Ask students to research the modern mythology of La Malinche. What function does La Malinche serve in Latin American culture? How does her myth compare with the facts of her life story? What do the differences reveal about the evolution of her story from fact to legend?

- Pair this life story with Life Story: Tecuichpotzin “Isabel” Moctezuma. How did the two women experience the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire? What differences and similarities can be found between their stories?

- Combine this document with either of the following resources for a lesson on how women played an important role as mediators between Indigenous populations and colonists in every colonial empire:

- Indigenous people across North and South America had a variety of responses to the arrival of European colonizers. Combine Malintzin’s life story with any of the resources below to explore:

- Malintzin’s marriage secured her freedom and economic well-being for the rest of her life. For other examples of women who used marriage as a way to improve their life circumstances, use any of the following resources:

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS