Document Text |

Summary |

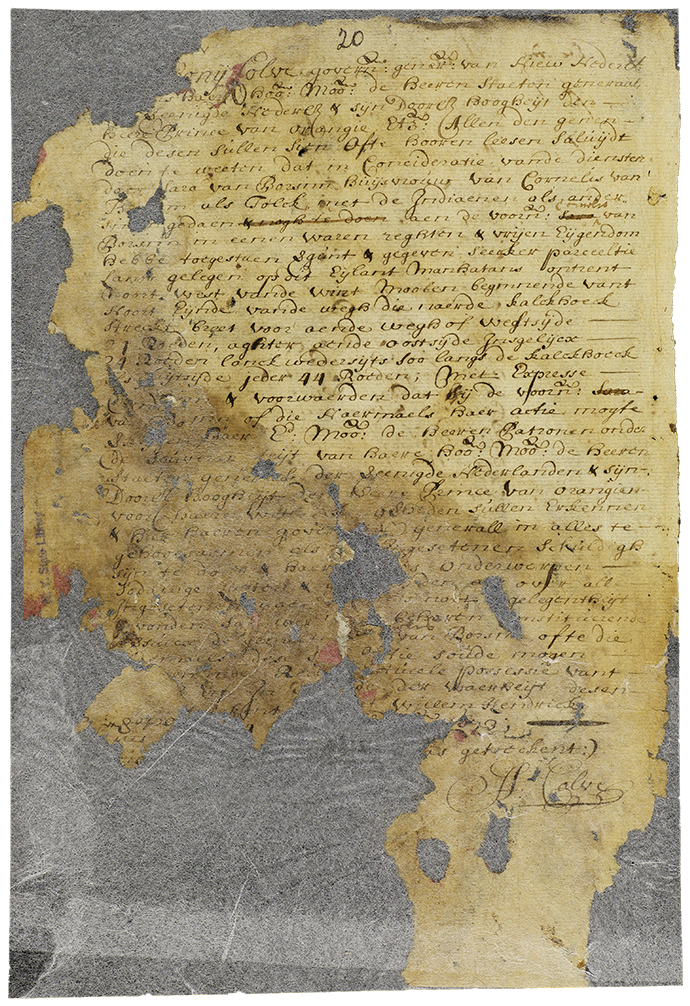

| Anthony Colve, Governor General of New Netherland On behalf of her High Mighty Lords of the States General of the United Netherlands & his August Highness the Lord Prince of Orange etc; |

The governor of New Netherland is speaking for the government of the Netherlands. |

| To all those who shall see, hear or read this, make it known that in consideration of the services of Sara van Borsum, housewife of Cornelis van Borsum, as interpreter with the Indians, the Governor General of New Netherland grants to Cornelis van Borsum a certain parcel of land situated on this Island Manhattan . . . | The governor of New Netherland grants land to Cornelis van Borsum as a reward for the work his wife Sara did as an interpreter with local Indigenous communities. |

Patent, October 14, 1673. New York State Archives. Translation by Eric Ruijssenaars.

Background

The colonists of New Netherland and the Lenni-Lenape people who lived in the lower Hudson Valley met daily to trade furs, negotiate land use, work for one another, and share news. But the relations between the two communities were not always friendly. Small disagreements could quickly turn into open war. Leaders on both sides relied on translators to communicate openly and keep the peace. Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum was one of the most trusted translators working for the New Netherland government. Her position was unique, as most translators in the early colonial period were Native American. The Lenni-Lenape assumed that, as a woman, she did not have the political or economic interests that might make her biased in negotiations. Because of this, they willingly accepted her as a translator. The Dutch government believed she was trustworthy because she was related to nearly all the most powerful families in New Netherland. Sara also had a natural talent for learning foreign languages. All of these factors made her an ideal translator in delicate negotiations. Her work was so important that she received rewards from both the Dutch and the Lenni-Lenape for her work.

About the Document

This document was written in 1673. At the time it was written, Dutch rebels had briefly taken control of New Netherland away from the English. The fact that rebels made a point of rewarding Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum during such a turbulent time speaks to how much she was valued by the Dutch community.

It should be noted that the land was granted to Sara’s husband instead of Sara herself. This shows that even important women were treated as dependents of their husbands in colonial Dutch society.

Vocabulary

- interpreter: A person who translates for two people who speak different languages.

- Lenni-Lenape: The collective name of the Indigenous people who lived in the lower Hudson Valley and northern New Jersey in the 1600s. Today, there are Lenni-Lenape communities in Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Ontario, Canada.

- New Netherland: The Dutch colony in North America, which encompassed land between the Connecticut and Delaware Rivers, and up the Hudson River to present-day Albany, New York.

Discussion Questions

- Why was Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum recognized by the Dutch government?

- Why were interpreters important in New Netherland?

- How did a woman become an important translator? What does this reveal about the place of women in New Netherland?

- Why was the land granted to Cornelis van Borsum? What does this reveal about the position of women in New Netherland?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 2.7 Colonial Society and Culture

- Include this document in a lesson about the trade relationships between European colonists and Indigenous communities. This resource highlights the importance of communication and trade between the different people living in these communities.

- Use this document to demonstrate how even women with important roles to play in the Dutch government still fell under their husbands’ jurisdiction in matters of reward or payment for their work.

- Pair this resource with Mohawk Interpreter. What did Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum and Hilletie van Slyck have in common? How were their experiences as translators different? How might each woman have related differently to the Native American and European communities they worked with?

- Combine this document with the image of the loopwagen in Childcare in Oneida and Dutch Communities to talk about how women had to balance their public lives with family responsibilities.

- Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum was one of the translators present when Quashawam sent her representatives to speak to the Dutch. Connect these documents to give students a more complete picture of why Sara’s work mattered.

- Combine this document with the following resources for a lesson on how women played an important role as mediators between Indigenous populations and colonists in every colonial empire. Ask students to compare and contrast the way each of these women came to her role as mediator, and what their experiences reveal about the colonial culture they inhabited:

- Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum worked as an interpreter because her intimate network of family and friends gave her the authority to do so. This kind of unacknowledged power network allowed women in many different colonial societies to exert influence far beyond what was traditionally available to them. Use any of the following resources to explore this idea of intimate power networks further with your students:

- Sara Roelofs Kierstede van Borsum was not the only woman with influence in New Netherland. Invite students to compare and contrast her experiences with any of the women listed below:

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS