This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Kateri Tekakwitha was born in 1656 in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, just a few miles west of present-day Auriesville, New York. Her Mohawk name, Tekakwitha, means “she who bumps into things.” Kateri was the daughter of Mohawk Chief Kenneronkwa. Her mother Tagaskouita was an Algonquian woman who was adopted by the Mohawk before her marriage. This was a common practice among the Mohawk in the 1600s. They adopted new members to counteract the population losses caused by European diseases and fur trade wars. Because of this practice, the community Kateri grew up in included a diversity of Indigenous languages and cultures.

When Kateri was about four years old, her parents and younger brother died in a smallpox outbreak. Kateri survived the illness, but she was left with facial scars, damaged eyesight, and poor health. Kateri was adopted by her aunt, and her childhood was typical for a young Mohawk woman. She learned how to process animal pelts and make clothing from them; weave mats, baskets, and boxes from plant fibers; and plant, tend, harvest, and cook the crops that fed her community.

Kateri was about ten years old when her village was attacked by French colonists. Kateri and her family were forced to flee into the woods. To end the fighting, the Mohawk agreed to allow French Jesuit missionaries into their territory. The missionaries hoped to convert the Mohawk to Catholicism. They also encouraged converts to move to Catholic villages. Many Mohawk were hostile to the missionaries because the missionaries wanted the Mohawk to give up their traditions. Kateri’s older cousin converted and moved away a few years before the missionaries arrived, so her uncle forbade her from speaking to the missionaries who visited their village.

In 1669 the Mohawk were attacked by the Mahican, a neighboring tribe that wanted to take control of the fur trade. Kateri and other young Mohawk women worked alongside Jesuit missionaries to care for the sick and wounded. The missionaries’ work and teachings during this difficult time made a strong impression on Kateri. When she was thirteen years old, her family tried to convince her to marry one of her uncles. Kateri told her aunt that she never wanted to get married. This was a common path for Catholic women who wanted to become nuns. Kateri’s interest in Catholicism provided an alternative life path and the opportunity to make her own choices. In the spring of 1674 Kateri told a visiting priest that she wanted to learn more about his religion. The priest was delighted and began formally instructing her in the prayers and rituals of his faith. Kateri was baptized in 1676. She took the name Kateri in honor of Saint Catherine. Kateri’s community did not support her conversion. After enduring six months of ridicule and accusations of witchcraft from neighbors in her village, Kateri took the advice of her spiritual advisor and moved to the Jesuit settlement of Kahnawake.

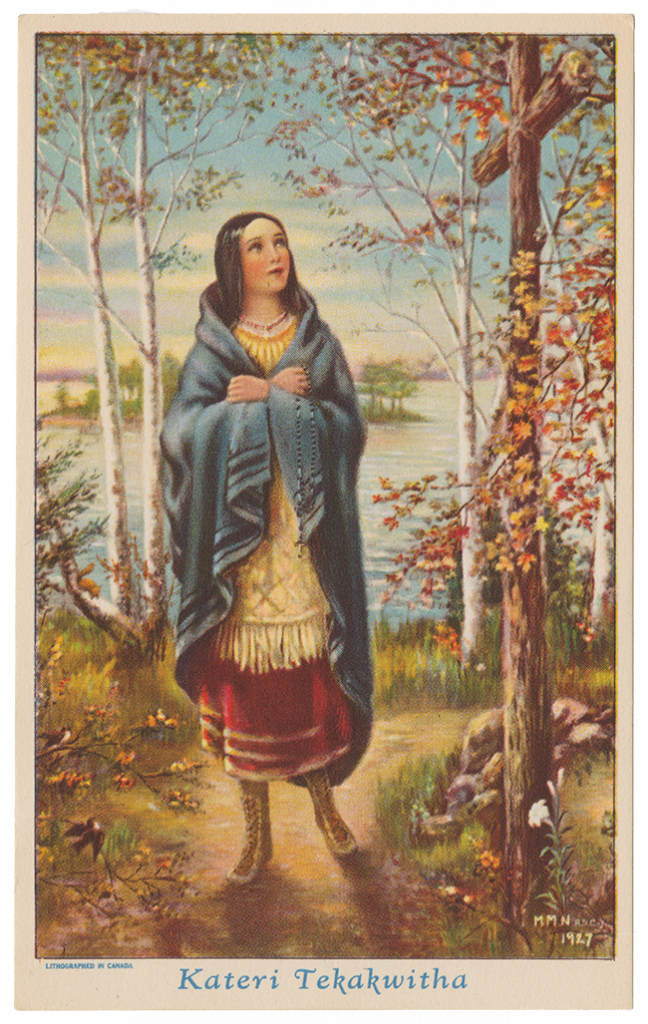

Kateri was officially canonized as the first Native American saint in 2012.

Kahnawake, located just outside of Montréal, was a safe haven and spiritual community for Indigenous men and women who converted to Catholicism. Daily life in the settlement was a blend of Indigenous and European practices. When Kateri arrived, she was welcomed by a warm community of Mohawk women converts just like her. Kateri’s mother’s close friend became her mentor in the community. Kateri’s cousin let Kateri live in her longhouse. Kateri also made new connections. Two of the most important were Marie-Thérèse Tegaiaguenta and Claude Chauchetière.

Marie-Thérèse was a young Oneida convert about the same age as Kateri. The two quickly became close friends. Claude Chauchetière was a Jesuit priest who had recently arrived from France. He was very enthusiastic about his mission to convert Indigenous people and was impressed by Kateri’s dedication to her faith. He became Kateri’s closest spiritual advisor.

Claude instructed the two young women in every aspect of their faith, and Kateri and Marie-Thérèse led their peers in the enthusiastic adoption of each new practice. They experimented with ritual fasting (not eating or drinking), self-mortification (deliberately injuring the body to make up for sins), and asceticism (extreme self-denial), all with the intention of bringing themselves closer to God. Kateri was inspired to engage in these rituals after hearing stories of several Catholic saints, but these kinds of practices were common in Mohawk spiritual life. It is likely that she would have been familiar with such ideas since childhood.

Kateri was always the most extreme in performing the new rituals. Sometimes Claude had to step in to stop her before she harmed herself. When Kateri and Marie-Thérèse learned about nuns, Kateri declared her intention of founding a convent. Claude was impressed with her willingness to completely abandon her former life. He held her up as a model for the entire conversion mission in New France.

The extreme punishments Kateri inflicted on herself did not help her already poor health. Within a few years, Kateri’s body had been pushed to its limits. On August 17, 1680 Kateri died surrounded by the entire Kahnawake community. Everyone who witnessed her death later swore that within minutes her smallpox scars disappeared, and her skin became radiant. They interpreted this as a miracle and a sign that Kateri was a saint and built a chapel in her honor. Kateri’s story spread, aided by a book about her life written and published by Claude. Soon pilgrims began to arrive to pray at her burial site. Some reported miraculous healings, and Kateri’s community of followers grew over time. She was canonized by the Catholic Church as North America’s first female Indigenous saint in 2012.

Today Kateri’s legacy is contested. Catholics celebrate her as a symbol of their religion’s power to transform lives. But some members of the Mohawk community see her as a victim of the forces of colonization. Regardless of the interpretation of her story, her life demonstrates the way life changed for Indigenous women after the arrival of European colonists.

Vocabulary

- Algonquian: Term for the people who spoke the Algonquian language.

- baptize: A religious ceremony that makes a person part of a Christian community.

- canonize: To officially recognize someone as a saint.

- Catholicism: A Christian religion that is led by the pope in Rome.

- convent: The home of a community of nuns.

- devotion: Worship.

- Jesuit: A Catholic priest who belonged to the Society of Jesus. Jesuits in New France were devoted to the task of converting Indigenous communities to Catholicism.

- Kahnawake: A community founded by Jesuits just outside of Montréal as a place for Indigenous Catholics to live and practice their faith.

- longhouse: A large dwelling made of wood used to house extended families in Mohawk communities.

- Mahican: A tribe of Algonquian-speaking people who lived in the present-day upper Hudson Valley at the time of European contact. Today, descendants of the Mahicans live in Wisconsin as part of the Stockbridge-Munsee community.

- missionary: A person who travels around and tries to convert people to their faith.

- Mohawk: An Indigenous community that originally inhabited the area now known as New Jersey, New York, and southeastern Canada. One of the five founding nations of the Haudenosaunee. Today there are Mohawk communities in upstate New York and Quebec and Ontario, Canada.

- nun: A woman who takes vows to dedicate her life to the service of the Catholic Church.

- Oneida: An Indigenous community that originally inhabited the area now known as upstate New York. One of the five founding nations of the Haudenosaunee. Today there are Oneida communities in New York, Wisconsin, and Ontario, Canada.

- Ossernenon: A Mohawk village in western New York.

- pilgrim: A person who travels to a sacred place for religious reasons.

- saint: A person recognized by the Catholic Church for being especially holy or virtuous.

- smallpox: A deadly disease that caused fever and blisters in those who caught it, and left scars on survivors.

Discussion Questions

- What does Kateri Tekakwitha’s life reveal about the challenges the Mohawk faced in the 1600s?

- What life circumstances made Kateri Tekakwitha uniquely interested in the teachings of the Jesuit missionaries?

- Why were Kateri Tekakwitha’s actions lauded by Claude Chauchetière and the other missionaries she encountered? Why was she feared and ridiculed by her Mohawk community?

- What does Kateri Tekakwitha’s life story teach us about the colonization of New France?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 2.5 Interactions Between American Indians and Europeans

- Include this life story in a lesson about Indigenous responses to colonization. This life story highlights the influence of colonization and religion on Indigenous communities.

- Invite students to research the different interpretations of Kateri’s life and legacy and hold a class debate about how her story should be incorporated into the history of interactions between colonists and Native people.

- Pair this life story with Life Story: Marie Rouensa, another Indigenous woman who converted to Catholicism. What do their stories have in common? How did they approach conversion differently?

- Combine this life story with Education in New France for a lesson about the central role that women played in the colonization of New France.

- Compare and contrast the lives of Kateri Tekakwitha with A Nun Challenges the Patriarchy. What drew these women to a religious vocation? What did they gain from their choice? What did they lose?

- Indigenous people across North and South America had a variety of responses to the arrival of European colonizers. Combine Kateri’s life story with any of the resources below for a lesson on the differences in each woman’s engagement with European colonizers and the outcomes they achieved:

- Religion was a powerful force in the daily lives of women in the European colonies of the Americas. Combine this life story with any of the following resources for a lesson on colonial women and religious life:

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS