Marie-Josèphe Angélique was a Black woman born into slavery in Portugal around the year 1705. During her childhood she was bought and sold by different enslavers, and moved with them around the Atlantic world. Around the year 1725 François Poulin de Francheville, a prominent businessman from New France, bought Marie and brought her to work in his home in Montréal in New France.

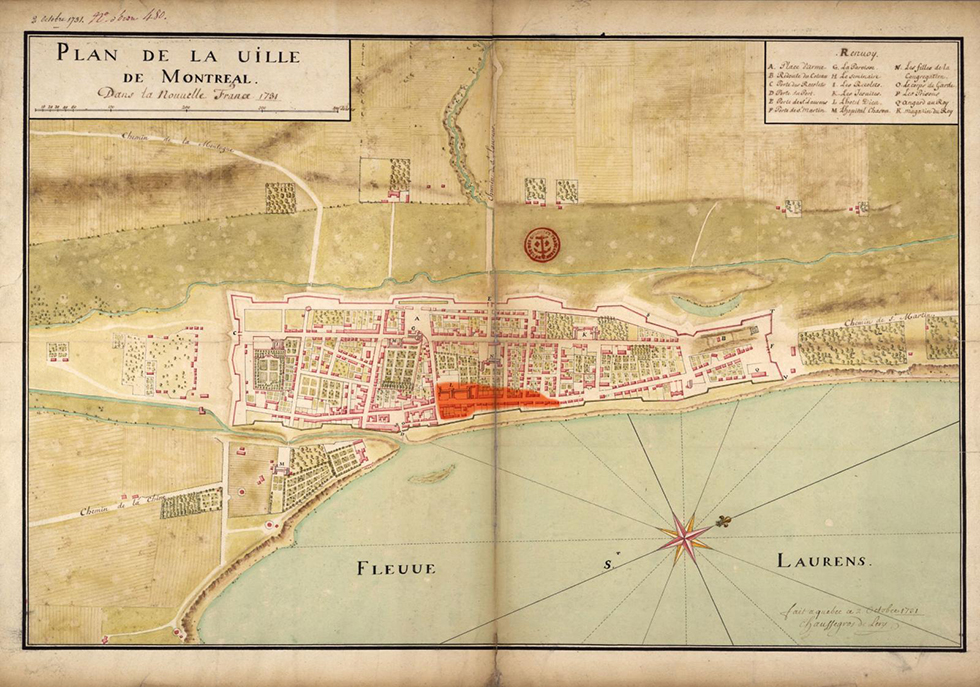

When Marie came to Montréal, it was a small city with a population of about 2,000. Like the other enslaved people in Montréal, Marie lived in the home of her enslavers. She worked under the daily supervision of her enslaver’s wife Thérèse. Marie was responsible for all of the domestic labor necessary to keep a prosperous household in working order, like cleaning, cooking, doing the laundry, and running errands.

In 1731 Marie gave birth to a baby boy who died after only a month. The next year she gave birth to twins, who only survived five months. The father of all three children was Jacques César, an enslaved man owned by a friend of Marie’s enslavers. The nature of the relationship between Marie and Jacques is not known. The experience of bearing and losing three children in two years while also being enslaved and required to perform all the labor expected of her must have been an immense strain on Marie.

Marie’s enslaver François died in 1733. Thérèse began the complicated process of settling his estate and taking over his businesses. During this chaotic time, Marie began to openly rebel against Thérèse. She started a relationship with an indentured servant named Claude Thibault and fought frequently with Thérèse’s white maid. Thérèse fired the maid and began to make plans to sell Marie. Marie knew enough about the Atlantic world to fear that she would end up on a sugar plantation in the Caribbean. She begged Thérèse to keep her, but Thérèse continued to make plans for her sale.

On February 22, 1734 Marie ran away with Claude. Their plan was to make it to the English colonies, where they hoped to catch a ship to Portugal. But harsh winter weather forced them to take shelter in a small town only ninety miles from Montréal. They were captured and taken back to the city. Claude was imprisoned for breaking his indenture contract, and Marie was returned to Thérèse.

Records assert that Thérèse did not punish Marie for running away, probably because she did not want to risk retribution or diminish Marie’s value if she decided to sell her. Marie now lived in constant dread of being sold. She shared her anger, fears, and frustrations with other enslaved people and indentured servants who lived nearby. She told some of them that Thérèse would live to regret her decisions. These complaints and threats made an impression on her neighbors.

On the evening of April 10, 1734, a fire broke out in Marie’s neighborhood. Aided by strong winds, the fire quickly spread. When the night was over, forty-five homes and businesses had been destroyed, including Thérèse’s home and the city hospital. Hundreds were left homeless, and everyone wanted to know what had caused such a catastrophe.

To this day, historians debate whether Marie was truly guilty of the crime she was executed for, or whether she was a convenient scapegoat for a community in crisis.

Marie’s neighbors accused her of starting the fire on purpose. They told Montréal officials that Marie had threatened to punish Thérèse. Based on these reports, the city government arrested Marie on April 11, and launched a full investigation to determine whether she was guilty.

French courts in the 1700s operated very differently from the modern American legal system. Court sessions were held behind closed doors, and cases were decided by a single judge. Defendants were not allowed to have lawyers. They were expected to appear before the judge alone and convince him of their innocence. Torture was freely used to get confessions. In these circumstances, Marie, an enslaved woman with an established history of rebellion and a well-known grudge against her owner, had to convince the judge that she was innocent.

Over the next six weeks, Marie endured four official interrogations and over a dozen “confrontations” during which she was allowed to challenge each witness the court had against her. The onslaught was intended to confuse and intimidate her, yet through it all she maintained her innocence.

The trial came to a head on May 27, when Thérèse’s five-year-old neighbor Amable told the judge that she saw Marie carrying burning coals to the attic before the fire broke out. She even identified the coal shovel Marie had used. Marie’s only response was to cry, “My little Amable, come here by me, and tell me who it is that told you to say this; I will give you a morsel of sugar.” In spite of the witness’s age, the judge decided that her testimony was proof enough to move Marie’s trial into the next, more serious phase. Marie was interrogated two more times in the “criminal seat,” a very low bench that allowed her interrogators to loom over her. This was a mandatory step in every trial for a crime punishable by death. Through these two more extreme interrogations, Marie continued to declare her innocence.

On June 4, the judge handed down his decision. He found Marie guilty, and sentenced her to a round of torture followed by execution. He hoped the torture would force Marie to name her accomplices. The sentence was carried out on June 21, 1734. During her torture, Marie confessed to setting the fire but refused to name any accomplices. She only begged the executioner to kill her. After her public hanging, her remains were burned and her ashes scattered to the wind. This incredibly severe treatment of a human being underscores the inhumane treatment of enslaved people. To this day, historians debate whether Marie was truly guilty of the crime she was executed for, or whether she was a convenient scapegoat for a community in crisis.

Vocabulary

- accomplice: A person who helps another commit a crime.

- Atlantic world: The term used to describe the cultural and economic ties that existed between Europe, Africa, and the Americas from the 1500s through the 1800s.

- estate: All of the money and property owned by a person.

- indentured servant: A person under contract to work for another person for a definite period of time without pay, usually in exchange for transport to a new place.

- Portugal: European country that shares a border with Spain on the Iberian peninsula.

Discussion Questions

- What does this story reveal about the experiences of enslaved people in New France?

- What specific challenges did Marie-Josèphe Angélique face as an enslaved woman?

- How did Marie-Josèphe Angélique assert her autonomy? What was the outcome?

- Marie-Josèphe Angélique maintained her innocence throughout her trial, and only confessed under torture. Do you think this confession is valid? Why or why not?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connections:

- 2.4 Transatlantic Trade

- 2.6 Slavery in the British colonies

- Use this life story in a lesson about the experiences of Black people in the American colonies. This life story illustrates the harsh treatment of enslaved Black women in New France.

- The entire court record for Marie-Josèphe Angélique’s trial is available for download here. Ask students to examine the evidence and determine for themselves whether she was innocent or guilty.

- Connect Marie-Josèphe Angélique’s story to the modern debate over the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” in modern-day terrorism investigations. What does Marie’s story reveal about the use of torture in criminal trials?

- Compare Marie-Josèphe Angélique’s quest for freedom with Fighting for Freedom in New Amsterdam and Petition for Freedom. Why did these women try different approaches to gaining their freedom? What do their stories reveal about the lives of enslaved women in their respective colonies?

- Ask students to compare and contrast the criminal trials of Marie-Josèphe Angélique with Life Story: Lisbeth Anthonijsen. What do their stories reveal about the treatment of Black women in New Netherland and New France?

- Marie-Josèphe Angélique was not the only woman in the colonies to stand trial for crimes she disavowed. Compare and contrast her experiences with any of the women in the following resources:

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS