General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagun: The Florentine Codex

Bernardino De Sahagún, Creator. General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex, 1577. Pdf. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667837/, World Digital Library.

Isabel Hernández was born in Guichiapa in Spain’s Mexico colony. From the time of her birth, Isabel was categorized as a mestiza, a woman of mixed Indigenous and Spanish heritage. Her father was a Spanish colonist. Her mother was also a mestiza with Indigenous and Spanish heritage. Historians do not know the exact year Isabel was born, but based on historical records it was probably between 1602 and 1612.

In 1650 two women contacted the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Mexico City to file a complaint against Isabel. The Holy Office of the Inquisition was a religious court with the authority to try people for crimes against the Catholic Church. The two women told the Holy Office of the Inquisition that Isabel was practicing witchcraft. Everything we know about Isabel comes from her testimony and the testimony of her accusers during her trial. Because of this context, it is difficult to determine the facts of Isabel’s life. Even so, her case provides important information about the lives of women in colonial Mexico.

The first accuser was Inés de Herrera, a forty-five-year-old widow. She gave her testimony on Monday, June 20, 1650. Inés told the court that she first met Isabel about twenty years earlier. Inés explained that her husband was abusive, and she heard Isabel might be able to help her. Inés said that Isabel gave her powders that would cure her husband. Inés decided not to use the powders, but she claimed that every time she talked to Isabel in the following months, Isabel asked if she had tried them. Inés claimed that a year after their initial meeting, Isabel told her how to kill a frog and turn it into powders that would poison any man she wanted to kill.

The second witness was Inés’s mother. She testified that Isabel offered women powders to cure their abusive husbands. What is curious is that both accusers waited twenty years to come forward. Some historians believe that people used the Inquisition as an opportunity to get revenge on members of their community. This means it is possible that these accusations were made to get back at Isabel for more recent offenses.

Whatever motivated the accusers, their testimony was taken seriously. On February 22, 1652 the Holy Office of the Inquisition decided to pursue a trial against Isabel. They arrested her and placed her in the secret prison of the Inquisition in Mexico City. They also seized Isabel’s possessions and sold them at a public auction. This was common practice for the Inquisition. The profits from the auction were used to pay for her housing and food during her imprisonment. The only possessions the court did not sell were Isabel’s religious objects and medications. These were submitted as evidence.

After Isabel’s arrest, new accusers came forward. Doña Beatriz de Nara y de la Mota told the court that Isabel removed two teeth from her mother’s body during her burial. She claimed Isabel believed Beatriz’s mother was a saint, and suggested that Isabel planned to use the teeth to create poison. González Lasio, an agent for the Inquisition, told the court that he heard rumors Isabel had provided the former governor, Don Diego de Villegas, with powder that would make any woman fall in love with him. Mariana de Alfaro said that she told Isabel that her husband was cheating on her and Isabel gave her instructions to make a poison that would make him no longer want to be with the other woman. Mariana said she did not follow Isabel’s instructions. She explained to the court that she only remembered this encounter when she heard about Isabel’s arrest.

Isabel made her first appearance before the Inquisition court on May 22. The Inquisition never told defendants why they had been arrested, to see what they could learn during interrogation. In Isabel’s first testimony, she was unaware what accusations had been made against her. She explained that she had been married and widowed four times. All of her husbands were originally from Spain. Her first husband was a blacksmith. She did not say how long they were married, but he died before they had children. Her second husband was also a blacksmith. They were married for around six years and had three sons together before he passed away. By the time of her arrest those three sons were adults. One was a silk weaver and the other two were basket weavers. Her third husband was a butcher, and they had a daughter, Juana. Isabel’s fourth husband was a shopkeeper, who had died by the time of the trial.

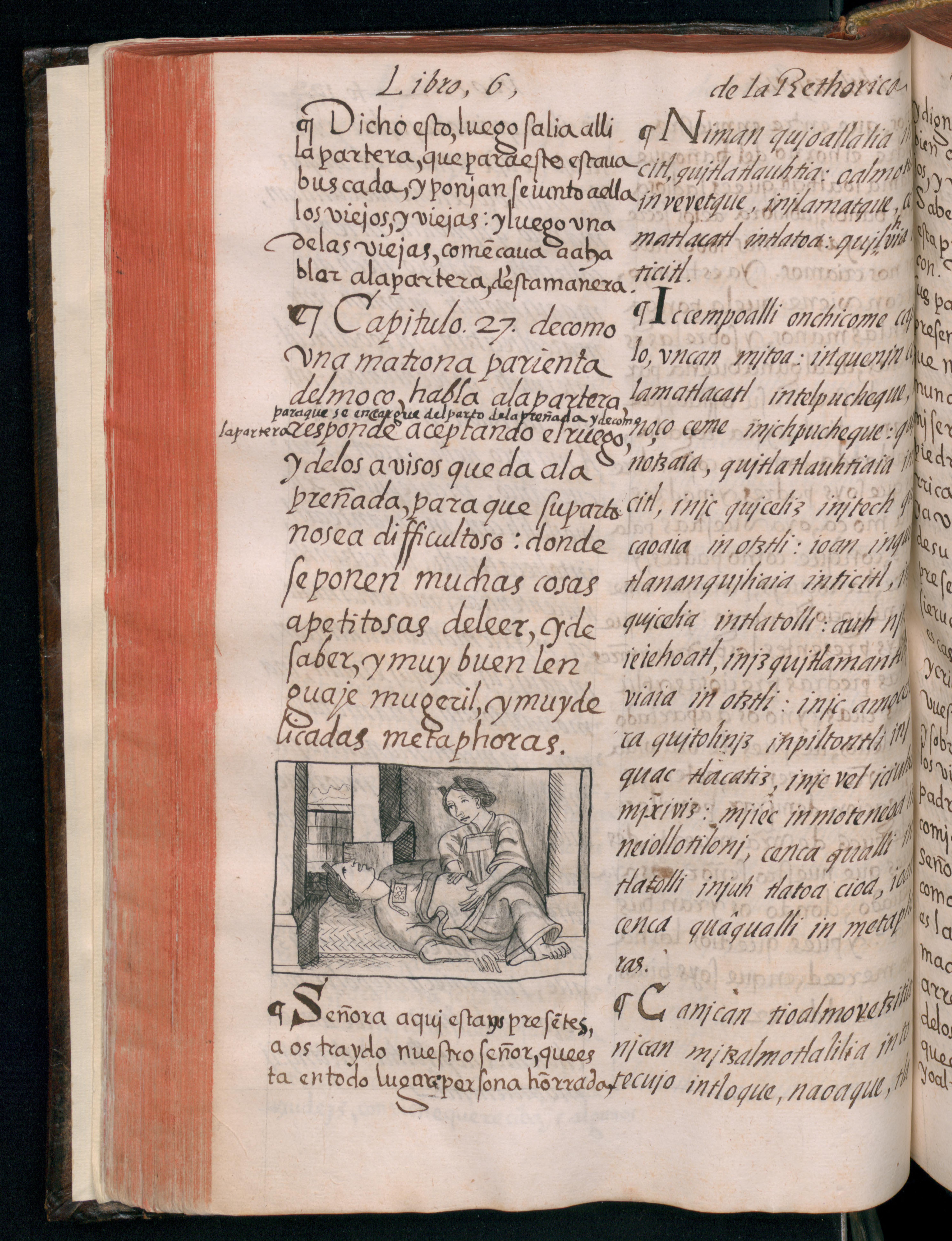

Isabel told the court that she supported herself and her family working as a midwife and healer.

Isabel told the court that she supported herself and her family working as a midwife and healer. She used Indigenous knowledge of the body and healing plants to care for the people in her community. Isabel’s work may have made her a target. Colonists from Spain were suspicious of Indigenous healing practices. There were many instances of Indigenous healers being accused of witchcraft.

Then the court asked Isabel whether she had any idea why she had been arrested. Isabel offered three possible explanations. First, a woman named Michaela had come to her for assistance about a year ago because her husband was controlling. Isabel confessed to selling Michaela some herbs. But she said that she knew the herbs were harmless and she only sold them because she desperately needed money for food.

Next, Isabel told the court that Don Diego de UIloa, former governor of Tlaxcala, sought her help. He had fallen in love with a married woman named Cathalina de Ortigossa and he wanted Isabel to bring Cathalina to him. Isabel brought Cathalina to his house one night. According to Isabel, Cathalina left the house after a short time and told Isabel that she felt troubled. When Diego came out angry, Cathalina suggested that he had done something inappropriate.

Finally, Isabel said a young pregnant woman came to her for help. The woman’s family believed she was a virgin, and the woman was afraid they would find out about the pregnancy. Isabel said she took the woman in and “cured” her with powders that same night. She did not say what happened to the fetus.

Isabel’s testimony reveals that she was aware she took part in actions that went against the teachings of the Catholic Church, but that she did not realize she had been accused of witchcraft. Her stories show that women in Tlaxcala frequently experienced physical and sexual abuse, often at the hands of their husbands and family members. But they also demonstrate the unique position Isabel held in her community. As a midwife, Isabel was someone women could turn to for help. As a mestiza, she was able to move more freely between the Indigenous and Spanish communities, giving her access and information other women lacked. But these qualities also made Isabel a figure of suspicion, someone who was not easily categorized or controlled. Historians still do not know whether Isabel committed any of the crimes she was originally accused of, or if her charges were made up by people uncomfortable with her outsider status.

The court was not impressed with Isabel’s testimony. They were particularly troubled by her seeming lack of remorse. They formally charged Isabel with witchcraft and recommended that she receive a harsh punishment. Isabel proclaimed her innocence. She appeared before the court two more times. Both times she reasserted that she told the truth and was not guilty of being a witch.

One hundred and five days after she was first arrested, the Inquisition found Isabel guilty of the crime of witchcraft. They exiled her from the state and sentenced her to serve in a convent. Isabel paid the court forty pesos to cover the cost of her time in prison. She does not appear in any other known records, so historians do not know what became of her after her sentencing.

Vocabulary

- Catholic Church: A Christian church that is led by the pope in Rome.

- convent: The home of a community of nuns.

- Don: The title for a Spanish man of rank.

- Doña: The title for a Spanish woman of rank.

- exile: Being forced to leave one’s home country.

- mestiza: A woman of mixed Indigenous and European heritage.

Discussion Questions

- Why was Isabel Hernández accused of witchcraft? What evidence was given against her?

- What role did the Catholic Church play in women’s lives in the Spanish colonies?

- What does the story of Isabel Hernández reveal about the experience of a working-class mestiza woman in the Spanish colonies?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 2.5 Interactions Between American Indians and Europeans

- Include this life story in a lesson about the Inquisition in the Spanish colonies. This life story provides students insights into the role of the Catholic Church in the community, and the life of a mestiza woman during the colonial period in Mexico.

- Pair this life story with Life Story: Doña Teresa de Aguilera y Roche. What did these women have in common? How were they treated differently by the Inquisition? How did their socioeconomic backgrounds affect their trials?

- Consider the experiences of Indigenous women in the Spanish colonies by teaching this resource alongside Life Story: The Gateras of Quito and Revolution in Art.

- For a larger lesson on witchcraft in this period, combine this life story with the following:

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS