Mary Todd Lincoln was born on December 13, 1818 in Lexington, Kentucky. Her father, Robert Smith Todd, was a banker, and her mother, Elizabeth Parker Todd, was an upper-class Southern housewife. Mary was the fourth of seven children.

When Mary was six years old, her mother died during childbirth. Her father took Elizabeth Humphrey as his second wife, and together they had nine more children. Mary did not get along with her stepmother, who once called her “Satan’s limb.” Despite this difficulty, Mary lived a privileged childhood. Her family was wealthy and they owned enslaved people who did all of the most difficult housework. Mary attended an elite school for girls, where she studied French, dance, drama, music, and the manners and responsibilities of an upper-class lady. By the time she graduated, she had a glowing reputation as a lively and intelligent young woman with a head for politics.

In October 1839, Mary moved to Springfield, Illinois, to live with her sister Elizabeth Porter Edwards. Elizabeth was married to the son of a former governor of Illinois. She introduced Mary to people in the best political circles. Stephen A. Douglas courted Mary, but she ultimately decided to marry Abraham Lincoln, a gifted young lawyer who belonged to the same political party as her family.

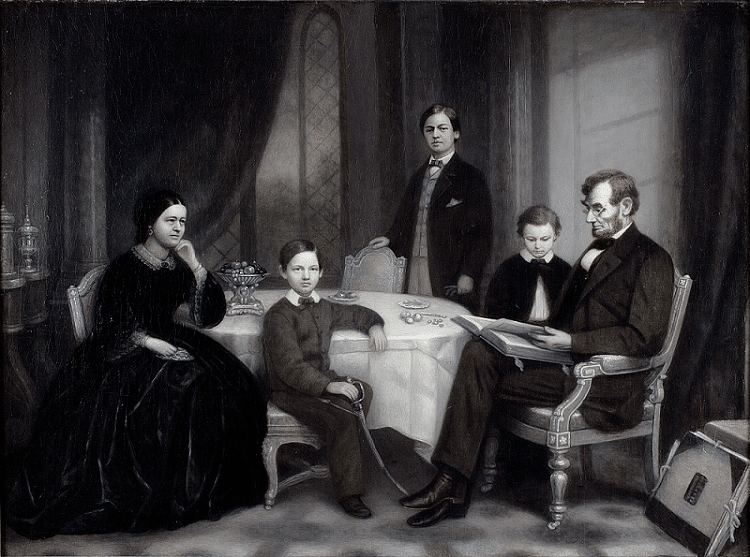

Mary and Abraham married at her sister’s home on November 7, 1842. Mary was 23 years old. A year later she gave birth to a son named Robert Todd after her father. Mary gave birth to three more sons in the next decade: Edward Baker in 1846, William Wallace in 1850, and Thomas “Tad” in 1853. Edward died of tuberculosis at the age of four, the first of many tragedies Mary would experience in her adult life. Edward’s death sent her into a depression. She would struggle with bouts of depression for the rest of her life.

Mary managed the Lincoln family home while Abraham pursued his increasingly successful legal career. It could be lonely work—Abraham sometimes traveled for months at a time. When Abraham ran against Stephen A. Douglas for the Illinois senate seat in 1858, Mary supported his campaign, even though his views on slavery caused tension within her slave-holding family. When Abraham was elected president in 1860, her family was torn apart. Kentucky joined the Union when Southern states seceded, but several of her brothers joined the Confederate Army. Through it all, Mary never wavered in her support of Abraham, believing wholeheartedly in his mission to preserve the Union.

When Mary moved to the White House in 1861, she assumed the role of First Lady of the United States. As First Lady, she was responsible for socially supporting all of her husband’s political work, creating a welcoming environment for political allies and foes alike. But she was the only First Lady who had to manage this daunting task as the nation tore itself apart. Mary threw herself into the project, redecorating the White House and doing her best to elevate the social scene. Many politicians in Washington criticized her efforts as frivolous, and even Abraham became angry when her renovations went way over budget. Mary struggled to find a balance between the role that was expected of her and the terrible realities facing the country. She supported the war effort by visiting hospitals and comforting the troops. She occasionally traveled to battlefields with Abraham to boost morale. But none of this was considered enough. She soon earned a reputation as the most unpopular First Lady in American history.

Mary’s struggle to be the First Lady her nation needed was compounded by the death of her 11-year-old son William in 1862. She was overcome with depression and did not leave her bed for months. Abraham hired a nurse to care for her. Mary eventually recovered, but her illness was not viewed with sympathy by a public that was receiving daily dispatches about the tragic losses at the front. Once again, Mary was criticized for failing to live up to impossible standards.

As First Lady, Mary was responsible for socially supporting all of her husband’s political work, creating a welcoming environment for political allies and foes alike. But she was the only First Lady who had to manage this daunting task as the nation tore itself apart.

On April 14, 1865, Mary had every reason to believe that her life was improving. The war was drawing to a close, the Union was going to achieve a total victory, and her husband had just started his second term in office. Mary believed she would spend Abraham’s second presidential term supporting him in his efforts to rebuild the nation. But that evening at Ford’s Theater, Mary was holding Abraham’s hand when he was shot in the head. The assassination put an end to the nation’s hopes for a smooth reconciliation, and it also destroyed Mary’s hopes of living a peaceful life with her remaining family.

Shortly after the assassination, Mary had to move from the White House to make room for the new president, Andrew Johnson, and his family. She settled in Chicago, Illinois, with her two surviving sons. In 1868, she was shocked when her dressmaker and confidant, self-emancipated businesswoman Elizabeth Keckley, published a memoir about her time working in the White House. Mary was particularly angry that Elizabeth had included private letters in the book. She felt betrayed by her friend, although they later reconciled.

In 1870, Mary won a small personal victory when Congress granted her a widow’s pension. Mary campaigned tirelessly for her pension, which she felt she was owed as the widow of the Commander in Chief. But her satisfaction was short-lived. Her son Thomas died from illness in 1871, plunging Mary once more into a deep depression.

Over the next few years, Mary became obsessed with the health of her remaining son, Robert. She also began to suspect that she was the victim of schemes to ruin her life and happiness. Given her personal history, these concerns were not entirely unwarranted, but Robert grew concerned with her erratic behavior. In 1875, he convinced a court to commit her to an asylum and he was granted full control of her estate. Mary was so devastated by the ruling that she attempted suicide.

Once her involuntary hospitalization began, Mary fought fiercely to regain her freedom, smuggling letters to her lawyers. When word of her hospitalization spread, people began to wonder whether Robert wanted his mother out of the way so he could control her fortune. He quickly agreed that she could leave the hospital to live with her sister Elizabeth in Springfield. In 1876, the court granted her control of her own estate again. Mary survived this attack on her personal liberty, but the episode drove a deep wedge between her and her only surviving son. They did not speak again for many years.

Mary spent the next few years traveling Europe, although she could never escape the American press. When she lobbied for an increase in her pension 1881, she was criticized once again for what many viewed as her frivolous spending. After suffering through this latest round of public humiliation, Congress granted her a pension increase and gave her a monetary gift as well.

Mary spent the last year of her life living with her sister in Springfield, where her remarkable life’s journey had begun. She died of a stroke at her sister’s home on July 16, 1882.

Vocabulary

- asylum: An institution that cares for the mentally ill. In the nineteenth century, asylums were infamous for their mistreatment of patients.

- Confederacy: The group of states that seceded from the United States before the Civil War in order to preserve slavery.

- estate: All of the money and property owned by a person.

- pension: A sum of money regularly paid to a former soldier for life in recognition of service.

- self-emancipated: A person who set themselves free from slavery. In Elizabeth Keckley’s case, she purchased her freedom with the help of her customers.

- tuberculosis: A deadly lung infection.

- Union: The name for the states that remained a part of the United States during the Civil War.

Discussion Questions

- What did Mary sacrifice in her support of her husband’s career and political policies?

- What were Mary’s responsibilities as First Lady?

- What criticisms did Mary face in her life? What do these criticisms reveal about the society she lived in?

- What is the value of learning Mary’s story apart from Abraham Lincoln’s?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 5.8 Military Conflict in the Civil War

- Include this life story in any lesson about the life and career of Abraham Lincoln.

- Read this story together with the life story of Elizabeth Keckley and then ask students to reflect on how each woman’s story broadens our understanding of the other.

- As First Lady, Mary Todd Lincoln served in a unique position for the duration of the American Civil War. To learn more about how Union women supported the war effort, use any of the following: Life Story: Sojourner Truth, Sanitary Fairs, Women’s War Production, Women Soldiers, Smuggling, Scenes from the Confederate Home Front, Changing the Rules of War, Life Story: Elizabeth Blackwell, Life Story: Emily Jane Liles Harris, Life Story: Loreta Janeta Velázquez, Life Story: Harriet Tubman, Swearing Loyalty, Nursing.

- Mary Todd Lincoln lost many loved ones in the course of her life. To learn more about how her bereavement created additional social conditions and restraints, read Mourning Clothing .

- Mary Todd Lincoln spent the years after her husband’s death fighting to maintain her standard of living in a world that did not support women living on their own. To learn more about the challenges faced by Civil War widows, read New York Exchange for Women’s Work.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS; DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY