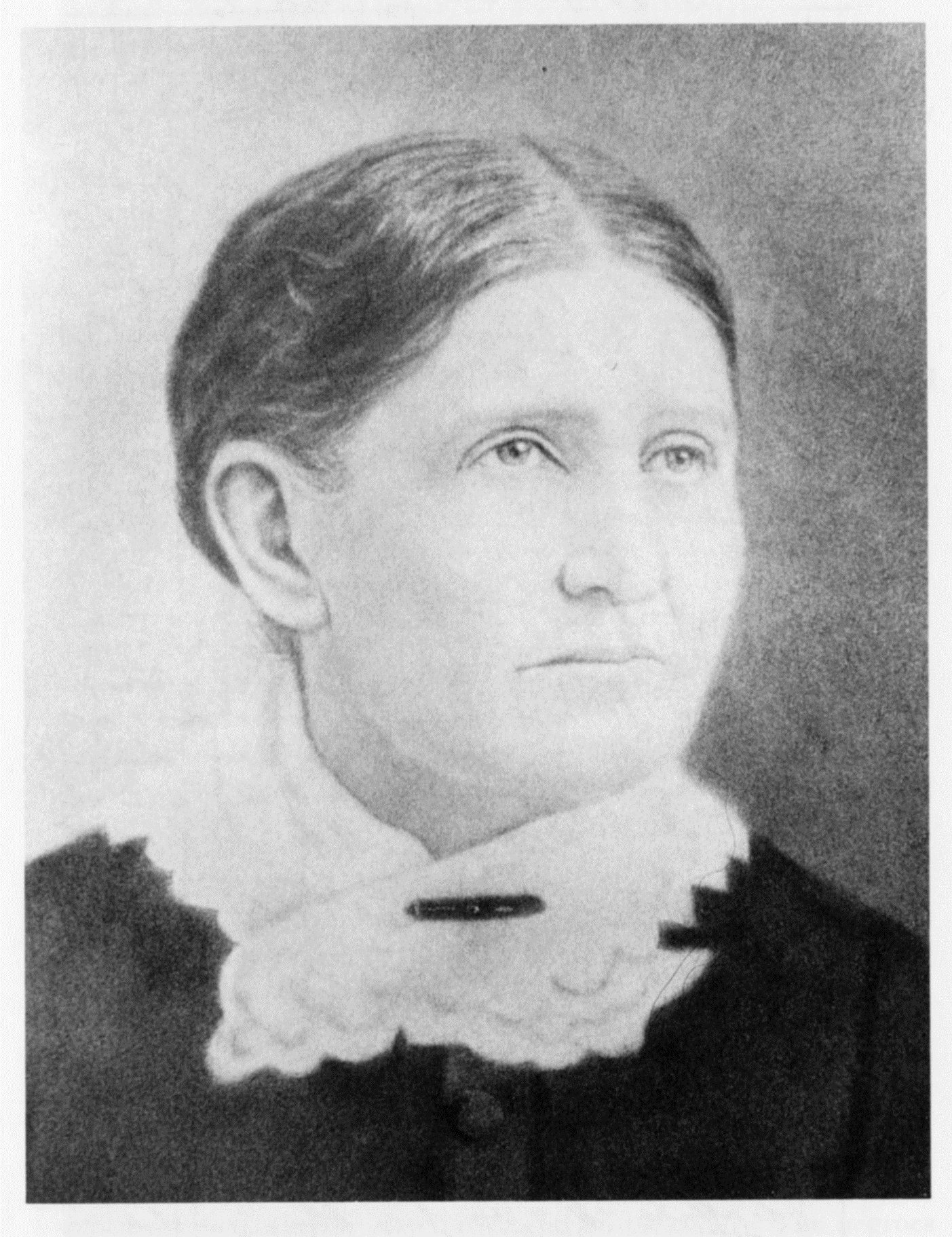

Emily Jane Liles was born on June 6, 1827 in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Her father, Amos Liles, was a farmer and slave owner. Her mother, Sarah, cared for their home and children. Amos and Sarah wanted their daughter to receive a good education. When she was young they sent Emily to live with cousins who had a private tutor. As a teenager, she attended the Spartanburg Female Seminary, where she developed her talent for writing.

On April 3, 1846, Emily married David Golightly Harris. David was the only son of a prosperous farmer and real estate developer in Spartanburg. David’s father gave him 50 acres of land to start his own farm. A few years later, Emily inherited her father’s farm and five enslaved people. By 1862, they had inherited a total of 1,000 acres of land and ten enslaved people. This put David and Emily in the ranks of the South’s commercial farmers and small-scale slave owners.

A commercial farmer is someone who grows enough crops to sell some at market for a profit. David and Emily did not grow cotton or other cash crops, and they never achieved the success of the plantation owners who ruled the Southern economy. They worked alongside the people they enslaved to raise crops and livestock. David managed the work in the fields and the sale of their goods. Emily managed the home and garden, as well as spinning, weaving, and preserving their food. They sold extra produce to buy shoes, farming tools, and other necessities they could not make themselves, and reinvested their small profits into improvements on the farm. They raised their seven children in a home with three small rooms.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, David and Emily supported South Carolina’s right to secede. But they worried about the effect the war would have on their family and community. A series of bad growing seasons had left them struggling, and they sought a new way to make money. In 1862, they started buying yarn and weaving it into jeans to sell. Emily oversaw their enslaved women in this work.

I am sick of losses, crosses, and disappointments.

In late 1862, David enlisted in the state militia to avoid being drafted into the Confederate Army. Like thousands of other Confederate women, Emily was left in charge of all the work on the family farm. Her first 35 years of life had not prepared her for this challenge.

Emily kept a detailed journal of her time as manager of the Harris family farm. Her journal illustrates how the war affected the lives of the Confederate middle and lower classes. Emily hated being left to manage everything, and often fell into depression. She constantly worried about her husband away at the front, and she could barely keep up with all of the work of the farm and household. Prices in the village were so high that Emily struggled to buy the small necessities her farm could not produce. Whenever David visited, he criticized her efforts, failing to take into account the enormous strain she was under. In December of 1863, Emily wrote that she would rather die than have to keep managing.

Emily found a way to carry on, even as the situation grew worse in 1864. David joined the Confederate cavalry, which meant he visited less and his life was in greater danger. The Confederate government raised taxes and ordered that all slave owners send at least one of their enslaved people to the front. Emily was furious with these demands and vowed to resist them as long as possible. Meanwhile, there was increasing unrest in the enslaved community of Spartanburg. Emily wished her husband was home because she feared her neighbors were taking advantage of her financially. Prices continued to rise, and the labor shortage meant she struggled to bring in their crops to make a profit. In September of 1864 she wrote, “I am sick of losses, crosses, and disappointments.”

David returned home for good in March 1865, shortly before Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, ending the Civil War. The Harris Family had survived the war, but they now needed to find a way forward. The abolition of slavery meant the loss of most of their labor force and personal wealth. David could no longer maintain the entire farm. He divided it into 50-acre plots that he rented to subsistence farmers. Emily, David, and their children worked hard to make their land profitable again, but they did not succeed. They were forced to sell some of their land, a blow David never recovered from.

David died in 1875. Emily continued to live and work with their children on the farm until her own death on March 26, 1899.

Vocabulary

- abolition: Legal end.

- cash crop: Something that is grown to be sold rather than used by the farmer. In the antebellum south, the main cash crop was cotton.

- cavalry: Soldiers who fought on horseback.

- commercial farmer: Someone who grows enough crops to sell some at market.

- Confederate: Relating to the group of states that seceded from the United States before the Civil War in order to preserve slavery.

- militia: Volunteer army.

- secede: Leave the United States to join the Confederacy.

- subsistence farmer: Someone who only farms enough produce to sustain their family and pay bills.

Discussion Questions

- How did Emily and her husband divide the labor on their family farm?

- How did the outbreak of the Civil War affect Emily’s life? How did she feel about these changes?

- What does this story reveal about the middle- and lower-class Confederate experience of the American Civil War?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 5.8 Military Conflict in the Civil War

- Include this life story in any lesson about the changes to home life during the Civil War.

- Compare and contrast Emily Liles Harris’s life story with the Union depiction of Confederate women in the political cartoon “Sowing and Reaping.” How does her experience challenge and complicate the narrative of this cartoon?

- Teach this life story together with Sarah Watie’s letter and the life story of Susie Baker King Taylor to explore how race affected these women’s experiences of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

- Compare and contrast this life story with that of Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas to explore how class affected women’s wartime experiences.

- For an in-depth lesson about the lives of Confederate women during the war, combine these images with the following resources: Smuggling, Scenes from the Confederate Home Front, Surviving the Siege of Atlanta, Changing the Rules of War, Civil War Political Cartoons, Swearing Loyalty, Cherokee Home Front, Life Story: Loreta Janeta Velázquez, and Life Story: Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas.

Themes

DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY; WORK, LABOR, AND ECONOMY