Keziah Grier was born around the year 1800. She spent her early years enslaved in South Carolina. When she was a teenager, her enslavers forced her to move with them to the Northwest Territory. Slavery was technically illegal in the Northwest Territory, but no one enforced this law. Like many other white settlers, Keziah’s enslavers brought her so she could do the difficult work of turning their new land into a working farm. It was a hard and dangerous life. Local Indigenous communities resented the arrival of settlers, and the outbreak of the War of 1812 brought violence to the area. But Keziah survived.

Keziah met Charles Grier soon after her arrival in 1815. Charles was a recently emancipated Black man who hoped to make a life for himself in the Northwest Territory. Charles bought 40 acres of land in what would become Gibson County, Indiana, and started the hard work of turning it into a farm. Keziah must have admired Charles’s work ethic, and the two fell in love. There is no record of how Keziah was emancipated, but she married Charles in 1818. As a newlywed, Keziah still spent every day doing the difficult work of turning wild land into a farm. But now her labor was building her future with Charles. They were important members of the community that would turn the Northwest Territory into an integrated part of the U.S., and they believed they were building a future where Black Americans could live as equals.

By 1828, Keziah and Charles had made a comfortable life, and Keziah divided her time between supporting the farm and raising their three children. But the community around them was changing rapidly. Hundreds of white settlers arrived every year. These new settlers resented the security and success of Keziah and other free Black settlers. One recent arrival from England tried to pressure the free Black community to move to Haiti to make way for white settlers. Laws were passed that limited the rights of free Black people. There was also the constant danger of slave catchers, who would kidnap any Black person they could and sell them in Missouri. Keziah feared the growing racism around her. She always kept a pot of water boiling over her fire, so she could use it as a weapon if her home was invaded.

But Keziah did not allow these threats to stop her from fighting for the equality she and Charles had dreamed of when they first married. Keziah and Charles were part of the Underground Railroad, a network of people who helped hide and transport refugees from slavery to safety and freedom. They secretly welcomed refugees into their home, provided them with food and water, and gave them a safe space to hide and sleep for a short while before they continued their journey. Keziah worked closely with David and Mary Stormont, white neighbors who lived 16 miles north. We don’t know how the two couples learned that they were both part of the Underground Railroad network. Revealing such a thing put a person in grave danger. But together, they helped many refugees pass safely on their way to freedom.

Keziah’s work with the Underground Railroad became more dangerous in 1850 when the U.S. passed the Fugitive Slave Act. This law made it legal for slave catchers to capture any Black person they suspected of being a refugee from slavery, even if they were living in a free state. The only evidence needed in court was for a white person to testify that a Black person was an escaped slave, which made it almost impossible for free Black people to prove their status if they were captured. The wealthiest Black farm owner in Keziah’s region was targeted by slave catchers, probably because his success had angered local white settlers. Even with all of his resources, it took the man more than a year to prove that he was born free. What hope did less wealthy free Black people have?

The Fugitive Slave Act also allowed severe punishments for any person caught helping refugees from slavery. Keziah and her family would have to pay a $1,000 fine if they were caught, an amount equal to over $32,000 today. But that is only if they were brought to court. Keziah knew that it was more likely that her family would be killed by a white mob enraged that they had dared to defy the institution of slavery.

Keziah’s work with the Underground Railroad became more dangerous in 1850 when the U.S. passed the Fugitive Slave Act.

Keziah was forced to face this terrible possibility in 1851. As usual, she helped a Black woman and her children before sending them on to the Stormonts. But the group was caught by slave catchers only a few days later. Fearful for his life, the white man leading the group asked the Stormonts for help, revealing that the Stormonts were part of the Underground Railroad. Now that the neighborhood knew that the Underground Railroad was operating in the area, every free Black family faced increased hatred and suspicion. Keziah must have been terrified, wondering if the white man or the captured refugees would name her family next. The man was tortured to death by local law enforcement, but he did not reveal Keziah’s family. The captured woman and her children were sent back to their enslaver in Alabama, where they were all brutally tortured. But they also never revealed who had helped them. Finally, in 1854, enough money was raised to purchase the freedom of the family. After three long years, Keziah could breathe easy, knowing that no one could be tortured into giving away her secret.

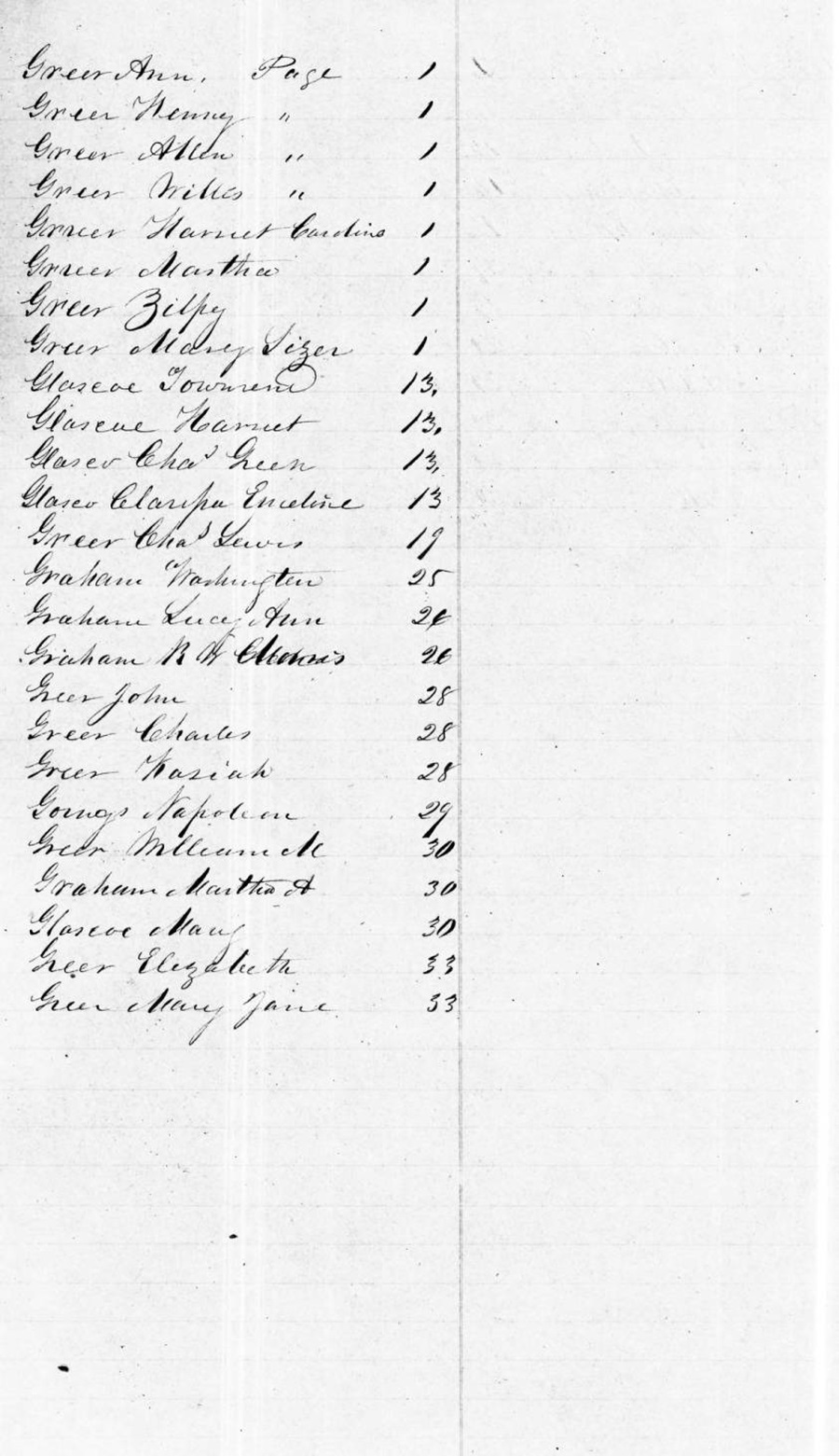

While Keziah and Charles waited anxiously to find out if their secret would be discovered, the state of Indiana took steps to make the lives of all free Black people in the state even more difficult than they already were. In 1851, Indiana passed a new state constitution that banned any new free Black person from settling in the state. Every free Black person who already lived in Indiana had to prove that they had settled in the state before 1851. They also had to submit to a physical inspection by white officials, so their features could be recorded in a register for future identification. Keziah and Charles had been among the first people to settle in Gibson County. They were the proud owners of a large, successful farm. But they were still forced to submit to this new humiliation.

Keziah and Charles continued on, tending to their farm and family. By this time, they owned 230 acres of land, and their three children were starting their own families. In 1853, their eldest daughter married the son of local free Black family. The newlyweds set up their home nearby, demonstrating that the free Black community of Gibson Country was determined to continue to survive and thrive no matter what limitations were passed against them.

Vocabulary

- Northwest Territory: The first territory of the United States, formed from lands won from England during the American Revolution. It covered land south of the Great Lakes, east of the Mississippi River, west of Pennsylvania, and northwest of the Ohio River.

- emancipated: Freed from slavery.

- register: An official list.

- Underground Railroad: Name for the network of people who helped refugees from slavery on their journey to safety and freedom.

Discussion Questions

- What role did Keziah Grier play in settling the Northwest Territory?

- How did Keziah Grier’s life change as more white settlers arrived in Indiana?

- Why do you think Keziah Grier continued to support the Underground Railroad, even in the face of mounting dangers?

- What does Keziah Grier’s story teach us about the lives of Black settlers in the American West?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 5.4 The Compromise of 1850

- Use this life story during any lesson on the settlement of the Northwest Territory.

- For more about the experiences of Black women settlers, see:

- Teach this life story together with Life Story: Harriet Tubman and Resistance , and then ask students to write a short narrative essay on the history of women and the Underground Railroad.

- Keziah Grier chose to stay in the U.S. after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. To learn how another Black family responded, see: Life Story: Mary Ann Shad Carey.

- Keziah Grier’s family’s success came at the expense of the Indigenous people who inhabited the lands the U.S. claimed as the Northwest Territory. To learn more, see Washington’s Captives and The Battle of Fort Dearborn.

- Compare and contrast Keziah’s experience as a settler with any of the following, and then ask students to write a response to the following prompt: How did race inform women’s experiences as settlers in the American West?

- To learn more about experiences of enslaved and free Black Americans in the antebellum period, see:

- The movement of American settlers westward had a devastating impact on the Indigenous communities that already inhabited those lands. To learn more, see:

Themes

AMERICAN CULTURE

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

To learn more about the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, see New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War