Lydia Carter was born into a chaotic and violent world. Her parents lived in Pasgua, an Osage town located in what we today call Rogers County, Oklahoma. There is no record of Lydia’s Osage name. The Osage is an Indigenous nation that lived on lands in present-day Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma. The U.S. government laid claim to those lands with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Under the direction of U.S. Indian Agent William Lewis, the Osage were forced out of parts of their territory before Lydia was born.

At the time of Lydia’s birth around the year 1813, the Osage were involved in an escalating conflict with the Cherokee Nation. To clear land for white settlers, the U.S. government forced the Cherokee to move from their traditional territory in Tennessee to lands once been occupied by the Osage. Cherokee and Osage warriors frequently clashed over hunting rights and territory disputes. When Lydia was only four years old, the conflict escalated to an all-out war. Cherokee warriors attacked Lydia’s town while most of the Osage warriors were away on a hunt. Lydia and her mother tried to hide, but her mother was killed and Lydia was captured. The Cherokee killed dozens of people and took 104 captives. Most of the captives were women and children.

Lydia was given to an Eastern Cherokee warrior as a reward for his help. The warrior traded her to another Cherokee man named Aaron Price. Aaron decided to bring her back to his home village in Tennessee. The journey was hundreds of miles and took many months.

Lydia met U.S. missionary, Elias Cornelius, while camping after a long day of travel. Elias was part of a group of religious Americans who believed that Indigenous people needed to be converted to Christianity and taught to live like white people. He was traveling throughout the western territories to convince Indigenous nations to build mission schools. Elias heard Lydia’s story and decided to save her from what he believed was a savage and hopeless future. He tried to convince Aaron to bring Lydia to the Brainerd Mission in Tennessee. Aaron wanted money in exchange for the girl. Elias promised that Brainerd would pay him. Elias continued on his journey to New Orleans. Lydia and Aaron continued moving east.

Lydia spent the next year living with Aaron in a small Cherokee settlement about 60 miles north of present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee. We know very little about her time with the Cherokee except that she learned to speak Cherokee and made friends with some children.

Meanwhile, Elias worked tirelessly to get Lydia to Brainerd. First, he raised $150 from a Mississippi woman named Lydia Carter. When Elias returned to Brainerd with the money, he discovered that the Cherokee expected the U.S. government was going to force them to return their Osage captives. Elias did not want Lydia to be returned to her Osage community, so he set out for Washington, D.C. He convinced President James Monroe to issue special orders that Lydia should be brought to the mission school. Just over a year after she was first captured by the Cherokee, Lydia arrived at the Brainerd Mission. We don’t know how she felt about being forcefully separated from the Cherokee community.

Lydia ran to the woods to try to avoid yet another separation from a community she had learned to love.

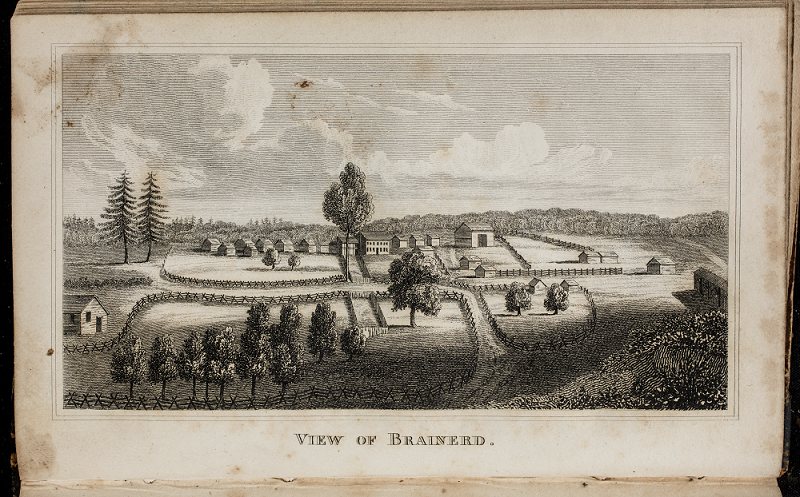

Brainerd was a mission school founded in 1817. The goal of the school was to convert Indigenous people to Christianity and teach them how to live like white people. When Lydia arrived, they named her Lydia Carter after the woman who gave money for her release. She was adopted by a white family that oversaw her education. She was given daily lessons in English and religion. She was also trained in the skills that a proper housewife would need upon marriage.

Just one month later, the mission was shocked to receive a message from a man claiming to be Lydia’s father. He thanked the missionaries for their interest in his child but asked that they return her to him. The missionaries could not understand why a man would want his child raised in a lifestyle they believed was savage and sinful. They decided they had the power to ignore his request. Their claim on the girl was backed by the president.

But in July of 1820, less than two years after Lydia arrived at Brainerd, U.S. policy disrupted her life yet again. The government wanted to establish better relations with the Osage, so they promised that all captives taken by the Cherokee in the 1817 war would be returned. This time, Lydia was old enough to fully understand what was about to happen. She ran to the woods to try to avoid yet another separation from a community she had learned to love. She was found and forced to begin the long journey back to the Osage Nation.

Lydia arrived at the meeting with the Osage in December 1820, where once again forces beyond her control took an unexpected turn. The Osage declared that the Cherokee could keep their captives. U.S. officials decided that Lydia should return to Brainerd, but Lydia caught malaria and dysentery on the journey. She was too weak to make the long trip. Lydia was placed in the care of a white woman who lived in Cherokee territory. The woman was instructed to nurse her back to health so she could return to Brainerd. Unfortunately, Lydia never recovered. She died on March 10, 1821. She was only about seven years old.

One year later, Elias Cornelius published a book about Lydia called The Little Osage Captive. He hoped her tragic tale would inspire young white people to support missionary efforts. The book is full of enthusiastic descriptions about how he and the Brainerd Mission tried to “save” Lydia. But it never acknowledges how her life was destroyed by the U.S. policies the mission supported. Today, the book and Lydia’s story are a haunting reminder of the trauma Indigenous people experienced because of U.S. western expansion.

Vocabulary

- Brainerd Mission: A Christian settlement that was founded to convert Cherokee people to Christianity and train them to live like white people. The Brainerd Mission was located near present-day Tennessee.

- Cherokee: One of the original Native nations that lived in the American Southeast. Despite 19th-century attempts to destroy it, the Cherokee Nation still exists, split into nations in Oklahoma and North Carolina.

- Christianity: Religion based on a belief in Jesus Christ.

- dysentery: An infection of the intestines that can be fatal if untreated.

- Louisiana Purchase: The treaty signed by Thomas Jefferson that acquired the Louisiana Territory from France.

- malaria: A deadly disease spread by mosquitos.

- mission: An effort to spread a religion to new people and places.

- missionary: A person who travels and tries to convert people to their religion.

- Osage: An Indigenous nation that once inhabited lands that cover parts of modern-day Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Today, the Osage nation is based in Oklahoma.

- sinful: Something that is considered wrong according to a religious belief.

Discussion Questions

- What U.S. policies led to Lydia’s capture by the Cherokee in 1817?

- How many times was Lydia forced to separate from people she knew? How do you think these separations affected her?

- What does Lydia’s story teach us about the impact of U.S. western expansion?

Suggested Activities

- The book about Lydia Carter’s life was written by the white man who thought he was saving her from a life of savagery and sin. After reading this life story, invite students to read chapter six of The Little Osage Captive. Then ask the students to consider how an Osage writer might have written about the same events. Why is it important to consider the author’s perspective when reading historical texts?

- To learn more about the displacement of the Cherokee, read Life Story: Nanyehi Nancy Ward.

- To learn more about missions and mission schools, see: Propagating “American” Womanhood, Life Story: Toypurina, Life in the Mission System, Education in New France, and Life Story: Harriet R. Gold Boudinot.

- For a larger lesson about the ways Indigenous communities were impacted by U.S. western expansion, combine this life story with the following: Washington’s Captives, The First Seminole War, The Battle of Fort Dearborn, Life Story: Sacagawea, and Life Story: Harriet R. Gold Boudinot.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS