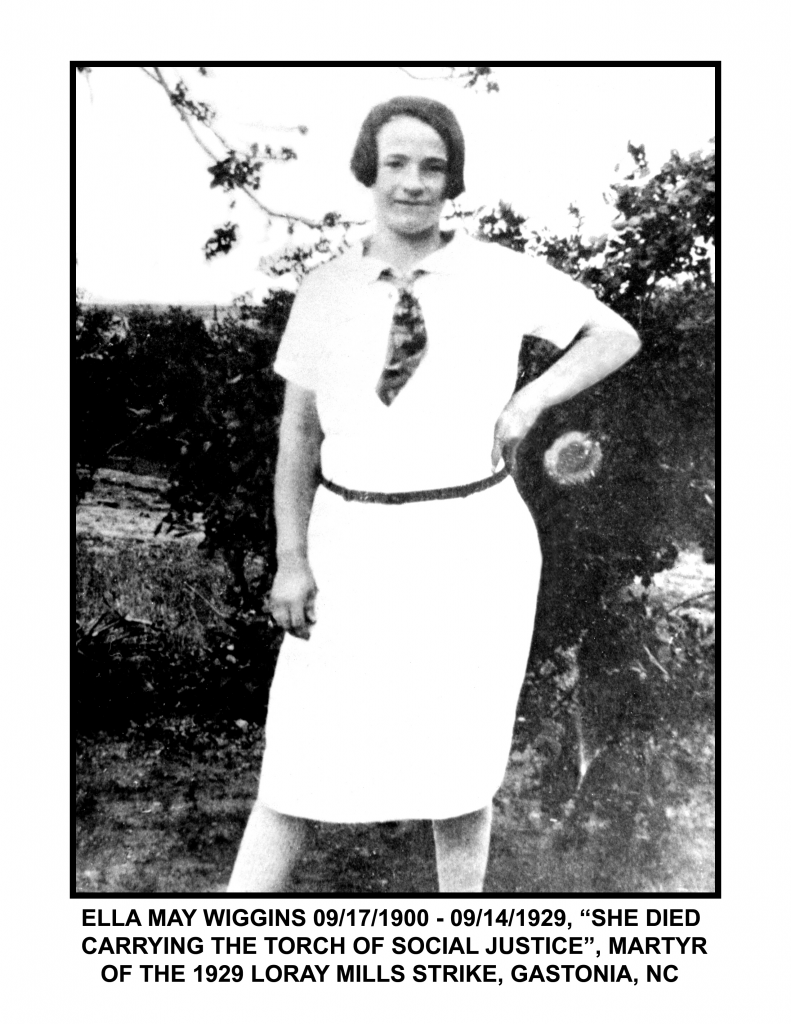

Ella May Wiggins was born in 1900 near Sevierville, Tennessee. She was the second of her parent’s twelve children. Ella May’s family moved often because her father worked in logging camps. Ella May and her mother contributed to the family income doing laundry for workers.

At the age of 14, Ella May married 23-year-old logger John Wiggins. The newlyweds lived near Ella May’s family, but not for long. Ella May’s father and mother and four of her siblings died of accidents or illnesses within six years. By 1920, Ella May had very little family left, the logging industry was in decline, and she and John had a growing family of their own.

Ella May, John, and their children moved from town to town looking for work before settling in Gaston County, the textile mill capital of the world. The pay at the mills was terrible, but Ella May needed money. She changed jobs often and hoped the next place would be better. But most mills were the same: long hours, high productivity demands, and low wages.

Ella May gave birth to nine children, but only five survived infancy. John was an alcoholic who left for days and weeks at a time, often taking Ella May’s hard-earned money with him. In 1926, he left and did not return.

At just 26, Ella May was the single working mother of five children under the age of eight. Her life was about survival. By 1929, she earned nine dollars per week working the graveyard shift for sixty hours a week. Six nights a week, she put her children to bed and went to work. In the morning, she returned home, made breakfast, and took care of her family while trying to rest.

Ella May tried to maintain some control of her life. She refused to live in the one of the mill-owned shanties. Instead, she lived in the African American neighborhood outside of town, where she briefly worked in one of the town’s only integrated mills.

On April 1, 1929, nearly 2,000 workers at the Loray Mill in Gastonia, North Carolina, went on strike. Loray Mill was one of the largest textile mills in the world. The strikers demanded a living wage and better working conditions. They were led by a Communist organization, the National Textile Workers Union. When the union invited Ella May’s mill to join the strike, she was one of the first to walk off the job.

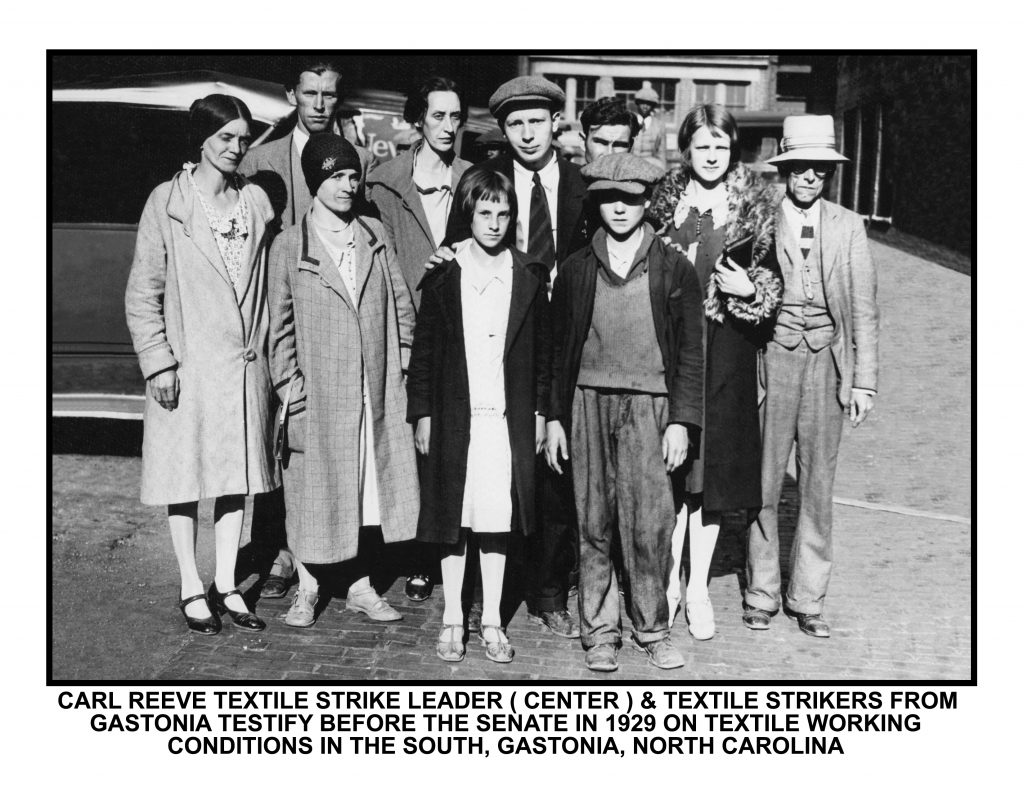

Ella May was convinced the union was the only way to give her children a better life. She spoke at rallies, joined picket lines, and attended meetings. She traveled with a small delegation to Washington, D.C., to testify before the Senate. The Senate adjourned before the strikers could argue their case, but Ella May did not stop there. She cornered a North Carolina senator in the hallway and yelled about the terrible mill conditions.

The mill owners fought back hard. They kicked tenants out of the mill-owned houses and hired “mill thugs” to harass strikers. By late spring, many people returned to work. But a dedicated group of 300 strikers, including Ella May, refused to back down. The remaining strikers set up a camp on the outskirts of town and continued to picket and host rallies. Altercations with mill sympathizers and local police were often violent. In June, police officers raided the strikers’ camp. The raid turned violent and the chief of police was killed.

Most of the town’s elite sided with the mill owners, especially after a police officer died. Local newspapers wrote that the strikers were un-American, un-Christian, and immoral. They took particular issue with the women strikers. They claimed that female strikers were too independent and outspoken. They dressed like flappers with bobbed hair, short skirts, and men’s hats. Because they weren’t working, they walked around the town during the day, contributing nothing to society. Worst of all, female strikers were active in picket lines and did not shy away from clashes with mill thugs. The local press argued these women were destroying the values of the Old South.

The strikers were even more unpopular when they began to consider racial integration. Ella May was at the forefront of this effort. She worked with Black labor leaders and encouraged them to join the strike. Black laborers were invited to one union meeting, but were asked to sit in a segregated section. Ella May crossed the line and sat with the Black workers in a show of solidarity.

We’re going to have a union all over the South,

Where we can wear good clothing and live in a better house.

Now we must stand together and to the bosses reply,

We’ll never, no, we’ll never let our union die.

Ella May had an unusual talent for music. She wrote over twenty original protest songs. The songs used traditional melodies and included simple and repetitive lyrics. Her most popular song was “The Mill Mother’s Lament,” which described what it was like to leave her children behind every day and why the union was her only source of hope.

On the afternoon of September 14, Ella May and other strikers rode in a truck to attend a rally. A group of men associated with the mill armed with guns ambushed them on the side of the road. Ella May, who was pregnant, was shot in the chest and died. No one else was killed, leaving many to conclude Ella May was assassinated. Her independence, talent, and belief in racial and economic equality were threats to the mills.

The strike dissolved within weeks. Although mill workers saw her as a martyr to an important cause, they were also terrified by the violence of her death.

Five men were charged with Ella May’s murder. Over fifty eyewitnesses testified against them, but the jury returned a not guilty verdict in under thirty minutes. Labor activists were devastated. One union leader wrote an article that argued the decision proved the life of a mill worker was considered worthless.

Ella May’s songs became her legacy. Historians recorded her work as examples of folk protest songs, and famous folk singers like Pete Seeger (to learn more about Pete Seeger, read his life story in the Hudson Rising curriculum) and Woody Guthrie publicly performed and praised her work. The fight for workers’ rights continued across the country for decades, and Ella May’s words were there to provide solace and instill solidarity.

Vocabulary

- assassination: The murder of an important person because of his or her beliefs.

- communism: A political system in which all goods and items of value are collectively owned and distributed to citizens equally.

- delegation: A group of representatives.

- graveyard shift: An overnight work schedule.

- martyr: Someone who is killed for his or her beliefs.

- racial integration: Combining people of different races in one place or organization.

- thug: A violent person. In the case of strikes, a company may hire thugs to break up picket lines and discourage strikers from taking action.

Discussion Questions

- Describe Ella May’s upbringing. What challenges did she face and how did that shape her adult life?

- Why was Ella May drawn to labor activism? Why did she believe that participating in a union was the only way out of her situation?

- Why were Ella May’s protest songs an important part of the Gastonia Textile Strike?

- Why was Ella May assassinated? Why do you think mill owners saw her as a particularly dangerous threat?

- What does the jury’s verdict tell you about the justice system in the 1920s South?

Suggested Activities

- Combine this life story with the image of a pregnant textile mill worker to help students understand the horrible working conditions women like Ella May faced each day.

- Compare Ella May Wiggins’s life story to those of Clara Lemlich and Emma Tenayuca and consider why and how women were active participants in labor movements.

- Explore the (frequently violent) challenges of labor activism in the 1920s and 1930s by combining Ella May Wiggins’s life story with Emma Tenayuca’s life story and the images of ILGWU strikers.

- Some of Ella May’s contemporaries described her death as a lynching. Explore the definition and history of lynching and its connections to racial and economic prejudice using Ida B. Wells’s life story.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS; AMERICAN CULTURE