Document Text |

Summary |

| The real question is whether the statute was intended to include persons who have, by law, no wills of their own. The statute extends to persons who have freely renounced their relation to the State. Infants, insane, femes-covert, all of whom the law considers as having no will, cannot act freely. | The real question is whether this law can apply to people who don’t have legal rights. The law specifically says it covers people who freely gave up their citizenship. Children, mentally ill people, and married women don’t have legal rights. Therefore, they cannot freely act, and this law does not apply to them. |

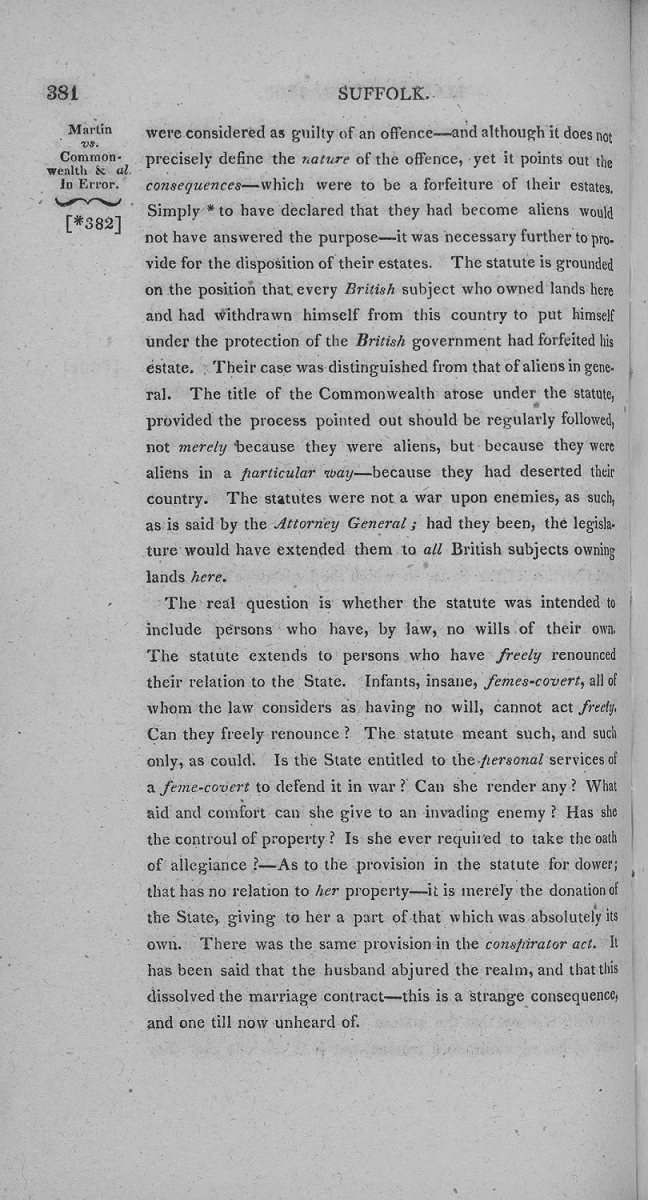

Martin v. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1805. Library of Congress.

Background

The legal status of women was not addressed in the U.S. Constitution. This meant that in the early years of the country, it was up to the states and the courts to determine women’s rights. The 1805 case of Martin v. Massachusetts was a pivotal moment in this history.

The story behind the case goes back to the final days of the American Revolution. In 1783, William Martin and his wife, Anne Gordon Martin, moved to England, along with many other Loyalists who had no interest in living in the newly formed United States. The Massachusetts state government labeled them traitors and took all the property they left behind.

In 1801, William and Anne’s son James filed a lawsuit with the Massachusetts Supreme Court to get his family’s property back. He claimed that the property never belonged to his father because his grandfather had specifically left it to Anne. He then argued that it was illegal to take the property from Anne because as a woman she did not have the political freedom to be a traitor to her country. The courts agreed, and the property was returned to James, cementing the idea that women did not have their own rights and identities in the new nation.

About the Document

This quote is from the 1805 Massachusetts Supreme Court’s decision for the case of Martin v. Massachusetts. The author states that married American women, called femes-covert, are subordinate to their husbands and can have no free will. This idea, commonly called coverture, had existed in the United States since the colonial era. While coverture was not officially written into the Constitution, this court case set a legal precedent for coverture that would last for over a century.

Vocabulary

- Constitution: The governing document of the United States.

- coverture: A common law practice where women fell under the legal and economic oversight of their husbands upon marriage.

- Federal period: The early years of the United States, usually defined as 1790–1830.

- feme-covert: Legal term for a married woman.

- loyalist: A person who supported the British during the American Revolution.

Discussion Questions

- What does this quote say about women’s free will during the time?

- Who does this author compare married women to? What does that say about Federal period attitudes towards women?

- What affect did Martin v. Massachusetts have on American women?

Suggested Activities

- For a larger lesson about the implications of coverture for women, teach this document together with the following: Life Story: Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas, Coverture, The Will of Joseph Grover, and Life Story: Dolley Madison.

- To learn more about the Federal period debate over the mental capacities and capabilities of women, see On the Capabilities of Women.

- Teach this document together with the resources about women’s suffrage in New Jersey for a larger lesson about how women’s rights were circumscribed in the Federal period.

- Use any of the following to demonstrate how women circumvented the political and social restrictions placed upon them in the Federal period: Federalist v. Anti-Federalist, Benevolent Societies, Life Story: Dolley Madison, and Life Story: Margaret Bayard Smith.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP