Document Text |

Summary |

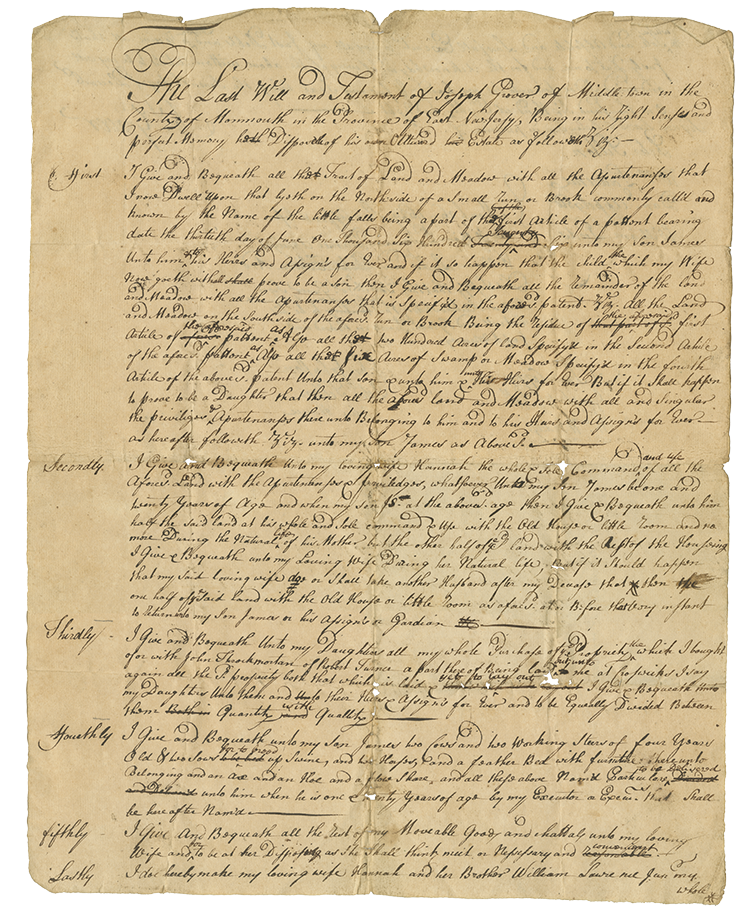

| This last will and testament of Joseph Grover of Middletown in the county of Monmouth in the Province of East New Jersey, being in his right senses and perfect memory has disposed of his outward estate as follows | Joseph asserts that he is writing this will when he is healthy and thinking clearly. If he dies, he wants his property to be given away in the following manner: |

| First, I give and bequeath all that tract of land and meadow with all the appurtenances that I now dwell upon that lies on the Northside of a small run or brook (…) unto my son James unto him and to his heirs and assigns forever. | First, Joseph gives all the land he owns on the north side of the brook to his only son, James. |

| And if it so happen that the child which my Wife now carries proves to be a son then I give and bequeath all the remainder of the land (…) that is specified in the aforesaid patent. All the land and meadows on the Southside (…)unto that Son and unto him and unto his heirs forever but if It shall happen to prove to be a daughter that then all the abovesaid land (…)follows Unto my son James as Above said. | Joseph explains that his wife is pregnant. If the baby is a boy, that boy will inherit all the land on the south side of the brook. If the baby is a girl, all the land on the south side of the brook will be given to his son James. |

| Secondly I give and bequeath unto my loving wife Hannah the whole and soul command and use of all the Aforesaid Land (…) until my Son James be one And twenty years of age and when my son is at the abovesaid age then I give and bequeath unto him half the said land at his whole and sole command and use with the Old House or little room and no more during the natural life of his mother but the other half of said land with the rest of the housing I give and bequeath unto my loving Wife during her natural life, | Second, Joseph gives his wife, Hannah, control of all his land and goods until their son James turns twenty-one. When James turns twenty-one, Hannah’s portion will be reduced to half of the family’s property until she dies. |

| but if it should happen that my said loving wife does or shall take another husband after my decease That then the one half of said land with the old house or little room(…) return unto my son James or his assigns on guardian. | If Hannah remarries, she loses all her land, and it will be given to James. |

| Thirdly, I give and bequeath unto my daughters all my whole purchase of the property which I bought with John Throckmorton from Robert Turner, a part thereof being laid out unto me at Crosswicks (…)… to be equally divided between them quantity with quality. | Third, Joseph sets aside a small piece of land that is not connected to the family farm for his daughters. They will divide the value of this land equally. |

| Fourthly I give and bequeath unto my son James two cows and working steers of four years old and his Sows for to brood up swine, and two horses, and a feather bed with furniture thereunto belonging and an axe and an hoe and a plow share and all these above named particulars to be delivered unto him when he is one and twenty Years of age by my executor or executors that shall be hereafter named. | Fourth, Joseph gives all the best household and farm goods to his son James. |

| Fifthly, I give and bequeath all the rest of my moveable goods and chattels unto my loving wife and for to be at her dispossessing as she shall think nice or necessary and convenient | Fifth, Joseph gives the rest of his household and farm goods to his wife Hannah. |

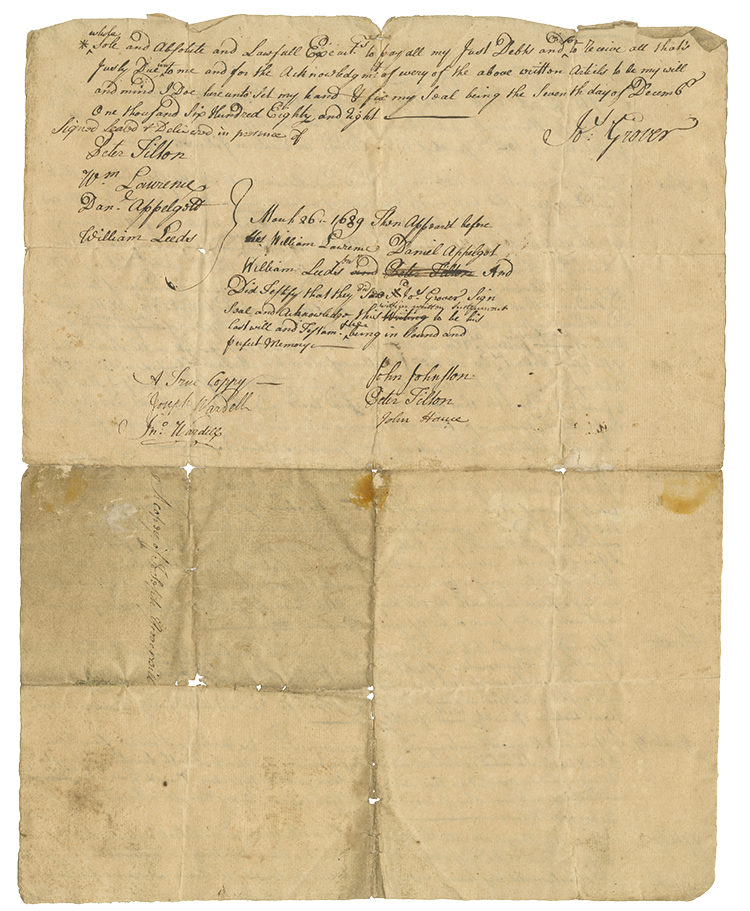

| I do here unto set my hand and fix my seal being the seventh day of December one thousand six hundred eighty and eight.

–Joseph Grover Signed sealed and delivered in the presence of: Peter Filson William Lawrence Daniel Applegott William Leeds |

Joseph signs and dates the will December 7, 1688. |

| March 26, 1689 then Approved before his William Lawrence(etc), And did testify That they see Joseph Grover sign Seal and acknowledge this within written testament to be his Last Will and testament there being in Sound and perfect memory | On March 26, 1689, one day after Joseph died, four witnesses signed the will, stating that they knew he had made it when he was healthy and thinking clearly. |

Joseph Grover, Last Will and Testament, 1688. New-York Historical Society Library.

Background

In England and its colonies, the common law practice of coverture determined women’s legal and economic status. Coverture meant that most women lived their whole lives under the legal and economic control of the men in their lives. This practice existed because it was widely believed that women were not intelligent or competent enough to appear in court or make business deals on their own. Before marriage, a woman’s interests were handled by her father. After marriage, that responsibility passed to her husband. This changeover was symbolized by a woman taking her husband’s last name. While coverture was meant to protect women, it limited their legal and financial power. They were allowed control over things that related to the care of their homes and families, but their options outside of their households were limited.

When a husband or father died, their property traditionally passed to the eldest son, who had a moral obligation to care for the widows and unmarried women in his family. But not all eldest sons fulfilled their duties. Some husbands and fathers left special instructions in their wills to ensure the financial security of their wives and daughters. The law required them to leave at least one third of their estate to their wives in order to ensure that widows did not become a drain on society.

About the Document

This is the will of Joseph Grover, who was an English landowner in New Jersey. It was written in 1688. The will shows how English laws and customs kept women and girls subordinate to the men in their lives.

Vocabulary

- coverture: A common law practice where women fell under the legal and economic oversight of their husbands upon marriage.

- inheritance: The things a person receives from someone who has passed away.

- will and testament: A legal document where a person describes how they want their belongings distributed after their death.

Discussion Questions

- What does this will reveal about the status of women in the English colonies?

- Why does the sex of Joseph and Hannah Grover’s unborn child change their inheritance?

- Why did Joseph Grover favor his sons over his daughters in his will?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 2.7 Colonial Society and Culture

- Include this document in a lesson about life in the English colonies. Wills offer intimate glimpses of the families and possessions of people long ago. Encourage students to consider what this document reveals about the experiences of women in 1600s New England.

- Couple this document with Coverture and ask your students to consider how this will (1) fits in with the common law practice of coverture, and (2) limits the prospects of Joseph’s wife and daughters.

- Ask students to use the descriptions of Joseph’s family and property in this will to reconstruct what daily life looked like for a farmer in colonial New Jersey.

- Pair this resource with Life Story: Frances Berkeley to explore the opportunities for widows who were able to inherit from their husbands.

- Compare and contrast the inheritance practices of the English colonists and their nearest colonial neighbors by combining this document with Life Story: Johanna de Laet and Life Story: Weetamoo.

- Teach this document along with Patent for Cleaning and Curing Corn for a broader picture of how coverture practices held back women in the English colonies.

- Women who fell outside the bounds of coverture—widows and unmarried women—were vulnerable to other forms of social control and coercion. Ask students to read this document along with Witchcraft in Bermuda and Life Story: Dennis and Hannah Holland.

- Compare and contrast the legal and economic rights of Colonial French, Spanish, Dutch and English women by coupling this document with the following:

Themes

DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY; AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For more resources relating to the practice of coverture, see Saving Washington: The New Republic and Early Reformers.