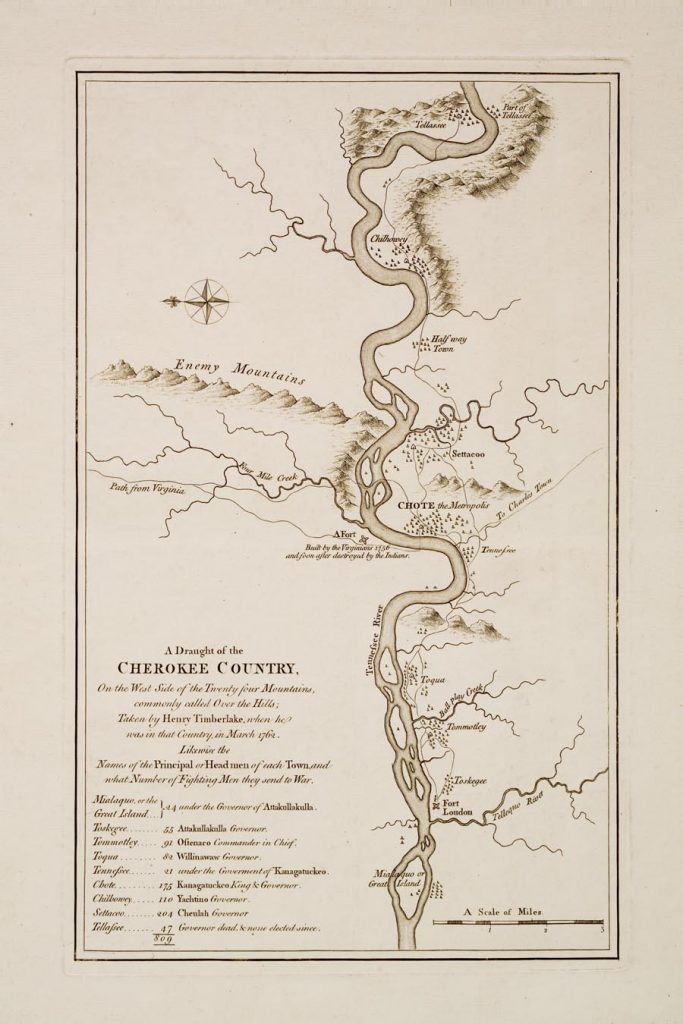

Nanyehi (“She who walks among the spirits”) was born in 1738 in the Cherokee town of Chota, in what is now eastern Tennessee. Cherokee society is matrilineal, so Nanyehi was born into her mother’s clan, the Wolf Clan. Through her mother, Nanyehi was the niece of Attakullakulla, an important chief in the Cherokee Nation. Throughout Nanyehi’s childhood, Attakullakulla pursued a path of cooperation with the British colonists who continually encroached on his people’s land. He believed that the best chance for Cherokee survival was for the two peoples to learn to peacefully co-exist. His beliefs had a profound impact on his niece.

Nanyehi rose to power in the Cherokee Nation when she was 17 years old. She was already married to a man named Tsu-la (“King Fisher”) and the mother of two children when she joined her husband on a Cherokee campaign against the Creek Nation. Nanyehi fought alongside her husband, reportedly chewing his lead bullets before he loaded them to make them more deadly. When Tsu-la was killed, she took up his rifle and led the warriors to a victory that expanded Cherokee territory in northwest Georgia.

For her courage and leadership, Nanyehi was named a Ghigau, a Beloved Woman of the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee believed that the Ghigau spoke with the authority of the spirit world and honored them accordingly. Nanyehi was given a seat next to the war and peace chiefs at the ceremonial fire in Chota. She led the Women’s Council of Clan Representatives, one of the two political bodies that governed the Cherokee Nation. She was the only woman with a vote in the other governing political body, the Cherokee General Council. She also had absolute power over the fate of prisoners taken in raids and battles.

In the late 1750s, Nanyehi married an English trader named Bryan Ward, and took the anglicized name Nancy Ward. Together they had one daughter. This marriage may have been part of her uncle’s larger efforts to create lasting bonds between the Cherokee and white settlers. Within a few years, Bryan returned to live with his English wife and family in South Carolina, and Nancy and her daughter visited them from time to time. Relations between the two families were friendly.

Like most communities living within the geographic area of the thirteen colonies, the Cherokee Nation was divided over how to respond to the outbreak of the American Revolution. Nanyehi and her uncle Attakullakulla counseled restraint and patience, while her cousin and his son Tsiyu Gansini (“Dragging Canoe”) wanted to take the opportunity to drive out colonists who had been slowly encroaching on Cherokee lands. In the summer of 1776, Tsiyu Gansini announced he would make a raid on the white settlements along the Watauga River, and asked Nanyehi to create the traditional black drink that would protect the Cherokee warriors during battle.

Nanyehi prepared the drink, but she also used her position as Ghigau to counteract his plans. She released three white prisoners, told them about the raid, and asked them to hurry to warn the colonists. Her actions gave the white settlers time to evacuate most of the women and children to a fort and set up an ambush for Tsiyu Gansini.

Tsiyu Gansini was injured in the ambush and lost thirteen of his warriors, but he still sent the surviving members of his party to destroy the settlement. The warriors captured a woman named Mrs. William Bean, and brought her back to Chota. They planned to burn her alive, but Nanyehi stepped in and used her authority to save the woman. She eventually allowed Mrs. Bean to return to her people, where she joined the other prisoners freed by Nanyehi in spreading the story of the Ghigau who wanted her people to peacefully co-exist with the white settlers.

As Nanyehi and Attakullakulla had feared, Tsiyu Gansini’s attack sparked a full-scale war with the Americans. Soldiers invaded Cherokee territory from Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina in 1777, and destroyed all the major Cherokee towns except Chota, which was spared out of respect for Nanyehi. The fighting between the Cherokee and the Americans dragged on throughout the American Revolution, with Tsiyu Gansini always agitating for more war, and Nanyehi continually working toward peace.

In 1781, Nanyehi addressed the U.S. treaty commissioners who were working with conservative Cherokee leaders to negotiate a treaty to end the fighting. She believed that peace would come only if Native people and white settlers saw themselves as one people, and she thought only the women on the two sides could make this happen. “Let your women’s sons be ours; our sons be yours,” she said to the commissioners. “Let your women hear our words.” Nanyehi’s speech reflected the political and cultural importance of women in Cherokee society, but it baffled her American audience, who lived in a society where women were not allowed to participate in public life. Regardless, her reputation continued to grow, and, as the fighting became fiercer, American commanders made a point of helping Nanyehi and her family escape.

In November 1785, Nanyehi accompanied the new Cherokee chief Utsi’dsata (“Old Tassel”) to another council with the Americans. At this meeting, the Cherokee learned about the resolution of the American Revolution, and the Cherokee laid out their full grievances to the representatives of the new nation. A new treaty was signed, and Nanyehi spoke to give the treaty her blessing. Shortly thereafter, her daughter with Bryan Ward married the Virginia Indian commissioner, creating a new tie between the two nations.

Nanyehi’s actions during the American Revolution have earned her an honored place in American history, but her reputation among the Cherokee is complicated. Nanyehi played a critical role in moving the Cherokee Nation away from their traditions and toward a more Westernized way of life. She is credited with introducing slaveholding, cattle farming, dairy production, and spinning to her community, and her attitude of acceptance toward white settlers gave them the ability to encroach on Cherokee territory. Today some Cherokees consider her a traitor, while Tsiyu Gansini is considered a hero for advocating armed resistance.

Nanyehi believed that peace would come only if Native people and white settlers saw themselves as one people, and she thought only the women on the two sides could make this happen.

In the years after the Revolution, America’s white population grew quickly, and more settlers moved into Cherokee territory because the land was ideal for growing cotton. George Washington’s administration tried to prevent settlers from seizing Cherokee land illegally, but failed to stop them. Fighting between the Cherokees and settlers continued, and representatives from both nations signed many treaties that white settlers ignored.

Some Cherokee decided that the best course of action was to sell their remaining land to the settlers or the government in exchange for land farther west, but this was a controversial decision. In 1816, some Cherokee leaders signed a treaty that gave away a large portion of land in modern day Alabama in exchange for land in Arkansas. The Cherokee National Council called the treaty treason. On May 2, 1817, the Cherokee Women’s Council urged the National Council to hold on to what remained of Cherokee land. Nanyehi, nearly 80 years old, sent her son to read a written plea that was signed by twelve other women, including her daughter and granddaughter: “Our beloved children and head men of the Cherokee Nation, we address you warriors in council. We have raised all of you on the land which we now have. . . . We know that our country has once been extensive, but by repeated sales has become circumscribed to a small track. . . . Your mothers, your sisters ask and beg of you not to part with any more of our land.” Nanyehi had come to realize that her people were being driven from the peaceful coexistence she had championed her whole life.

But the land sales continued. In 1819, the U.S. government purchased a large portion of the Cherokee Nation territory that included Chota. Nanyehi became an innkeeper, and her son cared for her in her final years. She died in 1822.

Vocabulary

- Cherokee: One of the original Native nations that lived in the American Southeast. Today the Cherokee have reservation in Oklahoma and North Carolina.

- clan: A subgroup of a larger tribe or nation. There are six clans in the Cherokee Nation: Long Hair, Blue, Wolf, Wild Potato, Deer, Bird, and Paint.

- Creek: A confederacy of Muskogean tribes that lived in southern Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. Today they are known as the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and are based in Oklahoma.

- Ghigau: Cherokee title meaning Beloved Woman, often bestowed on women who demonstrated particular strength or courage. Ghigau were honored for their connection to the spirit world and wielded considerable political influence in Cherokee society. They led the Women’s Council of Clan Representatives and had a vote in the Cherokee General Council. They also had absolute power over the fate of prisoners taken in raids and battles.

- matrilineal: A society that traces kinship through the mother or female line.

Pronunciation

- Attakullakulla: ah-tak-KOO-la-KOO-la

- Chota: CHO-tuh

- Gansini: GAH-nuh-see-nee

- Ghigau: gee-gah-hoo

- Nanyehi: nahn-YEH-hee

- Tsiyu: SHEE-you

Discussion Questions

- How did Nanyehi rise to power in the Cherokee Nation?

- What does Nanyehi’s life story reveal about the role of women in Cherokee society?

- How did Nanyehi’s actions affect her people and U.S. history?

- What does this story teach us about the responses of Native communities during the American Revolution?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.5: American Revolution

- Include this life story in any lesson about the impact of the American Revolution on Native communities.

- Compare and contrast Nanyehi’s experience of the war with Madam Sacho’s. What do these stories reveal about the ways Native women were affected by the American Revolution? What accounts for their different experiences with the Americans?

- Invite students to research the different interpretations of Nanyehi’s life and legacy, and hold a class debate about how her story should be incorporated into the history of interactions between American settlers and Native people.

- Native people across North and South America had a variety of responses to the arrival of white settlers. Combine Nanyehi’s life story with any of the resources below, and ask the students to write about the differences in each woman’s engagement with European colonizers and the outcomes they achieved: Life Story: Weetamoo, Life Story: Malitzen (La Malinche), Life Story: Quashawam, Life Story: The Gateras of Quito, and Revolution in Art.

- Teach this life story along with any of the following for a lesson about the many ways women actively participated in both sides of the American Revolution: Spinning Wheels, Spinning Bees, A Call to Arms, The Edenton Tea Party, Sentiments of an American Woman, Life Story: Margaret Corbin, and Life Story: Lorenda Holmes.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS; AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP; GEOGRAPHY AND THE ENVIRONMENT

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For resources relating to the American Revolution in New York, see The Battle of Brooklyn.