Document Text |

Summary |

| Within the Movement, debate rages over organizational and political strategy for the women’s liberation movement. This debate rarely includes the ideas of black women. So we rapped with six women, members of the Black Panther Party, about some of the issues raised by the women’s liberation movement and their own experience with women’s liberation inside the Black Panther Party.

… |

This is a conversation between a reporter from a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee publication (“Movement”) and six women members of the Black Panthers. |

| MOVEMENT: How has the position of women within the Black Panther Party changed? How have women in the Party dealt with male chauvinism within the Party? | MOVEMENT: How has the Black Panther Party changed its relationship with women? |

| PANTHER WOMEN: There used to be a difference in the roles (of men and women) in the party because sisters were relegated to certain duties. This was due to the backwardness and lack of political perspectives on the part of both sisters and brothers. Like sisters would just naturally do the office-type jobs… They were naturally given to the sisters and …the sisters accepted it so willingly because they had been doing this before . . . it was very easy for male chauvinism to continue on… | PANTHER WOMEN: Men and women used to have different jobs in the Party. This was the fault of both men and women. Women were given more office work. But women did not speak up because they were used it. |

| We’ve recognized in the past 4 or 5 months that sisters have to take a more responsible role. They have to extend their responsibility and it shouldn’t be just to . . . things women normally do . . . a lot of sisters have been writing more articles, they’re attending more to the political aspects of the Party, they’re speaking out in public more and we’ve even done outreach work in the community.. . . It’s been proven that positions aren’t relegated to sex, it depends on your political awareness. | In the last few months, women have started to speak up. They are doing more jobs now. They are writing articles, making speeches, and leading political activities. Party members are starting to realize jobs should be assigned based on skills, not gender. |

| We realize that the success of the revolution depends upon the women. For this reason, we know that it’s necessary that the women must be emancipated. | Women must be free in order for the revolution to be a success. |

| MOVEMENT: Could you explain what you mean when you say that the success of the revolution depends on the emancipation of women? | MOVEMENT: What do you mean? |

| PANTHER WOMEN: It’s because of the fact that women are the other half. A revolution cannot be successful simply with the efforts of the men, because a woman plays such an integral role in society even though she is relegated to smaller, seemingly insignificant positions.

… |

PANTHER WOMEN: Women are half of the population and play an important role. A revolution can’t be successful if half of the population is not free. |

| MOVEMENT: Black women are considered to be the most oppressed group in the US, as blacks and as women. That special oppression gives them a special, even vanguard, role. Do you want to talk about that a little? | MOVEMENT: Many people think Black women are the most oppressed people in America, which gives them an important role to play. Can you talk about what this means? |

| PANTHER WOMEN:

… I think it’s important that within the context of that struggle that black men understand that their manhood is not dependent on keeping their black women subordinate to them because this is what bourgeois ideology has been trying to put into the black man and that’s part of the special oppression of black women. Black women as generally a part of the poor people of the US, the working class, are more oppressed, as being black, they’re super-oppressed, and as being women they are sexually oppressed by men in general and by black men also. … |

PANTHER WOMEN: Black men need to understand that their strength is not dependent upon women being in second. That is what white people in power want Black men to think. Black women are oppressed by multiple forces because even Black men look down on them. |

| MOVEMENT: What are your ideas on the strategy for women’s liberation in terms of separate women’s organizations, the priority of women’s liberation in relation to other issues like imperialism and racism? | MOVEMENT: What do you think about the women’s liberation movement? |

| An example of this is…where occasions arose from time to time where women would want to have a caucus and a man would come around and they would get very uptight that a man was there and were practically ready to jump on him, just because he happened to be listening around. I think that’s an example of how the women’s struggle is taken out of perspective—it is separated from class struggle in this country, it’s separated from national liberation struggles and it’s given its own category of women against men.

… |

For example, sometimes women activists do not want men to attend their meetings. I think this is wrong. These women forget that the main problem is class. Liberation must come from men and women, not women against men. |

| The contradiction between men and women is a contradiction that has to be worked out within the revolutionary forces . . . It’s the class struggle that takes priority. To the extent that women’s organizations don’t address themselves to the class struggle or to national liberation struggles they are not really furthering the women’s liberation movement…in order for women to be truly emancipated in this country there’s going to have a to be a socialist revolution…

Any organization that’s being formed for women’s liberation…can’t operate separately and by themselves… It’s not being realistic and looking at things as a whole…If they’re not careful, they will go to an extreme and they will become female chauvinists. |

Women’s liberation groups need to recognize that the bigger revolution is about class. If they do not recognize this, they are not helping women. In order for women to be free, they must contribute to a bigger revolution.

It is not realistic for women to exclude men from the fight. They risk becoming chauvinists. |

Panther Sisters on Women’s Liberation article, 1969. The Movement newspaper, Chicago History Museum.

Background

The late 1960s was a transformative time for Black women. Black Power and women’s liberation were gaining momentum. Black women were inspired by both revolutionary movements, but they fit into neither perfectly. Middle-class white women dominated the women’s liberation movement. Many, but not all, leaders promoted the importance of racial diversity within the movement. Yet even the most inclusive white woman could not understand what it meant to be Black. Similarly, the men leading the Black Power movement did not know what it meant to be a woman.

The Black Panther Party is an example of an organization where Black women capitalized on this unique political moment. Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panther Party in October 1966. The following spring, 16-year-old Tarika Lewis joined as their first female member. Tarika and many other women felt inspired by the organization’s message of self-defense and pride. Seale and Newton based their ideology on militant masculinity. However, they did not define their ideology in terms of female submissiveness. Yet they did not clearly explain how women fit into the group. Panther women saw this as an opportunity to define their roles for themselves. Over the years, they created a vision of female Black militant power. Women founded or led many local party chapters. They also led many of the Party’s core programs, including the famous free breakfast initiative.

About the Document

This resource is a page from the September 1969 issues of the Movement newspaper. Movement was published by a group of volunteers for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) of California. Their goal was to cover interesting stories about the civil rights movement.

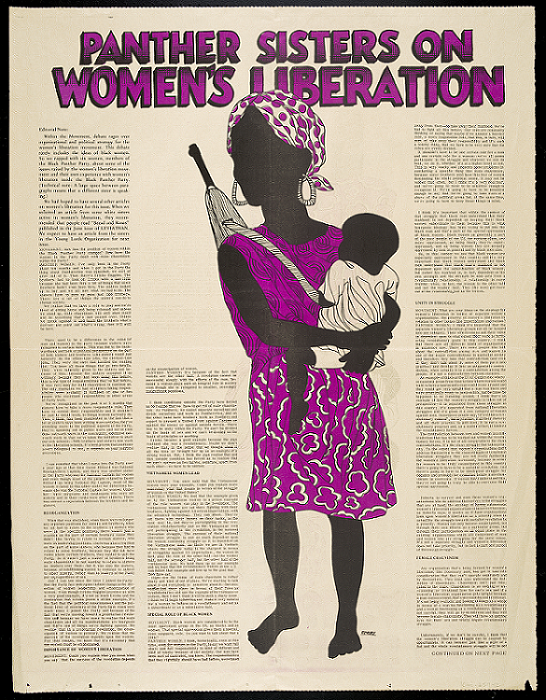

The image at the center of this page is by Emory Douglas, the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. Emory’s graphic art helped to explain the Party’s ideals through visuals. Depictions of women often included children and guns, which spoke to their dual role as mothers and revolutionaries.

The text around the image is an interview with six Panther women. The text provided is an excerpt of the longer interview. In it, a reporter from Movement asks the women to reflect on women’s liberation within the Black Panther Party and beyond.

Vocabulary

- Black Power: A civil rights concept that promoted racial pride and solidarity among Black Americans.

- Black self-defense: The idea that Black civil rights activists should defend themselves against violence by fighting back and carrying weapons for protection.

- bourgeois: Relating to the middle class, particularly the white middle class.

- capitalize: Take action to benefit from something.

- chauvinist: A person who aggressively shows prejudice.

- emancipated: Freed or liberated.

- Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC): A national organization founded to recruit and organize young people interested in the civil rights movement.

Discussion Questions

- What do you see in the image? What does this tell you about how the Black Panthers viewed Black women?

- Why did Movement publish this interview? What do you think motivated them to talk to Panther women?

- How do the women describe gender dynamics within the Black Panther Party? What caused this to change? Who is responsible for correcting gender dynamic problems?

- Why do the women believe that women must be emancipated in order for the Black Panthers to be truly successful?

- How do the women feel about the women’s liberation movement? What concerns do they have?

- What do the women mean when they describe a revolution that is bigger than the women’s movement?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 8.10: The African American Civil Rights Movement (1960s)

- AP Government Connections:

- 3.6: Amendments: Balancing individual freedom with public order and safety

- 3.10: Social movements and equal protection

- 4.4: Influence of Political Events on Ideology

- Conduct a deeper analysis of the Emory Douglas graphic. Invite students to identify details and consider how the image defines Black women. Encourage students to conduct their own search for other illustrations by Emory Douglas and compare them to this image.

- Compare the Emory Douglas graphic to The Liberation of Aunt Jemima by Betye Saar. How does each piece speak to the other?

- Explore the divisions between feminists in this era by pairing this document with the document written by The Furies. The Panther women believe excluding men will hurt the revolution. The Furies believe women will only succeed if men are excluded. How does each group explain their position? What do students think about these two arguments? How might these groups learn to work together?

- Continue the study of divisions in the women’s liberation movement by pairing this document to Gloria Steinem’s testimony and Betty Friedan’s life story. How do students think the Panther women would have responded to these white leaders’ ideas?

- Many Black Panthers supported Shirley Chisholm’s run for President. Connect this document to materials from her campaign. Consider why her message of “Unbought and Unbossed” resonated with Panther men and women.

- Panther women were not the first to think about the intersection of race and gender. Connect this interview to the life story of Pauli Murray, who coined the term “Jane Crow” decades before the Black Panther Party took shape. How do students think Pauli might have felt about the Panther women’s comments?

- Explore the similarities and differences between the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords by comparing this document to the Young Lords’ 13-point program. How did Black and Puerto Rican women seek to position themselves within these various movements?

Deepen students’ understanding of the Black Power movement by combining this resource with the life story of Angela Davis and The Liberation of Aunt Jemima by Betye Saar.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE