Margaret Shippen was born on July 11, 1760 to a wealthy family in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her family called her Peggy. Her father, Edward Shippen IV, was a prominent judge and member of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, and her mother, Margaret, was from a family with a strong legal tradition. Peggy was the youngest of the Shippen family daughters, and a favorite from a very young age. She was educated in all of the womanly arts, like needlework, dancing, and music, but also displayed an early passion for following news and politics.

When the American rebellion began in 1775, Edward Shippen chose to remain neutral, but the fervent Philadelphian patriots accused him of having Loyalist sympathies. The family’s situation improved in 1777, when the British captured the city. At 17 years old, Peggy was the right age to attend the many balls and parties thrown by the British Army officers, and she earned a reputation for being beautiful, vivacious, and intelligent. She formed a particular friendship with Major John André, a dashing young officer who was also the spy master of the British Army. He drew the portrait of Peggy that accompanies this life story. During the British occupation, Peggy’s political opinions evolved, and she became an enthusiastic Loyalist.

The British Army withdrew from Philadelphia in June of 1778, and Major André went with them, but his role as spymaster meant he and Peggy could continue to write to each other. She likely sent him frequent updates about life in Philadelphia, which was taken by the Continental Army that summer.

Just like the British before them, the officers of the Continental Army threw frequent balls and parties, and invited all of the local women to attend. This is probably how Peggy first met the city’s new commander, General Benedict Arnold. Benedict was twice her age, and Peggy was captivated by his stature as a decorated war hero who seemed to be poised for further greatness. For his part, Benedict greatly admired Peggy’s beauty and accomplishments. And so, despite their seeming political differences, they married on April 9, 1779.

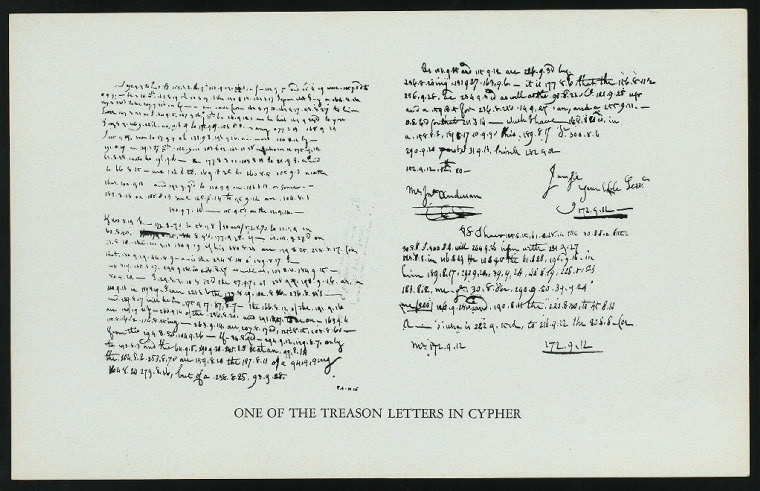

Peggy’s family was not thrilled that she was marrying a leader of the Continental Army, but Peggy may have already known that Benedict was growing frustrated with his position. His marriage to Peggy may have even been his first step in changing his loyalties. How large a role Peggy played in encouraging his change of allegiance is unknown, but it is a fact that in May 1779, only one month after their wedding, Benedict made his first contact with the British Army to offer his services as a traitor to the Americans. Peggy’s longstanding correspondence with Major André made her the perfect go-between for her husband’s negotiations with the British. She hid cypher messages in personal letters and letters of business, confident that no one would look too closely at the correspondence of the general’s wife. Over the next year, Peggy continued to foster her husband’s developing plan, even as she prepared to give birth to her first child.

But Peggy was not the only woman with eyes on Benedict’s plot. General George Washington had his own network of spies, called the Culper Spy Ring. These spies operated around New York City collecting information on the British. One of their number was a woman known only as Agent 355. In May 1780, the Culper ring passed along an explosive piece of information: an American general was plotting with Major André to help British Army take control of West Point. Washington and his advisors immediately began to take steps to catch the traitor.

Peggy hid cypher messages in personal letters and letters of business, confident that no one would look too closely at the correspondence of the general’s wife.

That summer, Benedict took command of West Point, and Peggy moved there with her newborn. Not knowing that the Americans were aware of their plot, they continued to communicate with the British, passing along plans that would make it easy for the British Army to take the fort in battle.

On September 21, the Americans managed to arrest Major André on his way home from a secret meeting with Benedict. Major André was carrying maps of the fort and a signed pass from Benedict himself. He confessed the plot and the Americans hanged him for his crimes. Only two days later, Peggy and Benedict were preparing to welcome George Washington for breakfast when they learned that Major André had been captured and their treason discovered. Benedict ran for his life, leaving Peggy to deal with the Continental Army officers who would arrive at any moment to arrest him.

When Washington and his officers arrived, Peggy put on the performance of a lifetime. She went into hysterics, screaming, crying, and swearing she had no knowledge of her husband’s plot. She begged Washington and his officers for mercy. Her performance was crucial: it not only convinced Washington of her innocence, it also caused enough of a delay that her husband was able to escape. Washington gave Peggy permission to take her baby and move back to her family in Philadelphia.

Peggy made her way to Philadelphia, but news of her husband’s treason preceded her, and the American officials running the city refused to let her stay. She went instead to New York City, where she rejoined Benedict. They lived there for rest of the war, moving to London in 1781 after the British surrender at Yorktown.

Peggy enjoyed the full support of the royal family and the British aristocracy when she arrived in London, but her life never lived up to the expectations she had when she married Benedict. Her husband traveled to Canada several times, always hoping to regain the prestige and power he had once had, but never quite succeeding. She frequently traveled with him, and over the years, she gave birth to seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood. Peggy returned to Philadelphia in 1789 to visit her family, but the general public still felt resentment toward her and Benedict. When Benedict died in 1801, she sold all of their property and most of her personal possessions to try to pay off their debts and support their children. She died, probably of cancer, only two years later.

Vocabulary

- Continental Army: The army formed by the Second Continental Congress and led by General George Washington.

- cypher: A secret or disguised way of writing.

- Loyalist: A person who supported the British during the American Revolution.

- Patriot: A person who supported the American rebellion during the American Revolution.

- Provincial Council of Pennsylvania: The governing body of Pennsylvania from 1682–1776.

- West Point: A military post on the Hudson River that was occupied by American troops beginning in 1778. Today it is the site of the United States Military Academy.

Discussion Questions

- Why were women spies used by both sides during the American Revolution?

- What does this story reveal about the way women were viewed and treated during the American Revolution?

- What does this story teach us about the activities of women in the American Revolution?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.5: American Revolution

- Include this life story in any lesson about Benedict Arnold or espionage during the American Revolution.

- Work with students to draw a web of all the major figures in this life story to better make sense of all the ways they were connected.

- Cypher played a critical role in keeping Peggy’s work from being discovered. Ask the students to study historical forms of cypher and then create their own.

- Peggy is part of a long history of women who have worked as spies or double agents during wartime. Use this story as a jumping off point for students to do their own research on another famous woman spy. Ask them to consider how her womanhood helped or hindered her work.

- Teach this life story together with the life story of Lorenda Holmes for a lesson on the substantial contributions made by women spies during the American Revolution.

- Teach this life story along with any of the following for a lesson about the many ways women actively participated in both sides of the American Revolution: Spinning Wheels, Spinning Bees, A Call to Arms, The Edenton Tea Party, Sentiments of an American Woman, Life Story: Margaret Corbin, Life Story: Lorenda Holmes, and Life Story: Nanyehi Nancy Ward.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For resources relating to the American Revolution in New York, see The Battle of Brooklyn.