Home / Modernizing America, 1889-1920 / Xenophobia and Racism / Black Life in the Urban North

Resource

Black Life in the Urban North

An article from The Chicago Defender that describes the new opportunities and challenges northern cities offered women looking to escape the horrors of the Jim Crow South.

- About

-

Curriculum

- Introduction

-

Units

- 1492–1734Early Encounters

- 1692-1783Settler Colonialism and the Revolution

- 1783-1828Building a New Nation

- 1828-1869Expansions and Inequalities

- 1832-1877A Nation Divided

- 1866-1898Industry and Empire

- 1889-1920Modernizing America

- 1920–1948Confidence and Crises

- 1948-1977Growth and Turmoil

- 1977-2001End of the Twentieth Century

- Discover

-

Search

Document Text |

Summary |

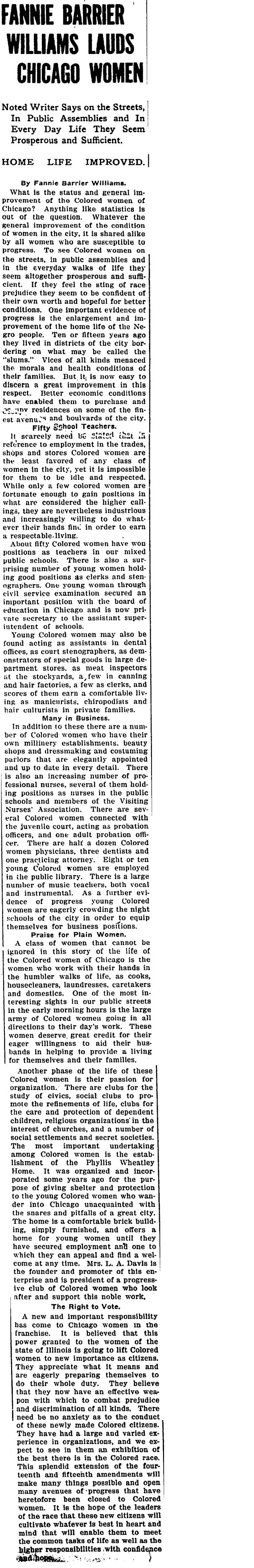

| FANNIE BARRIER WILLIAMS LAUDS CHICAGO WOMEN | FANNIE BARRIER WILLIAMS LAUDS CHICAGO WOMEN |

| Noted Writer Says on the Streets, In Public Assemblies and In Every Day Life They Seem Prosperous and Sufficient. HOME LIFE IMPROVED. What is the status and general improvement of the Colored women of Chicago? Anything like statistics is out of the question. Whatever the general improvement of the condition of women in the city, it is shared alike by all women who are susceptible to progress. To see Colored women on the streets, in public assemblies and in the everyday walks of life they seem altogether prosperous and sufficient. |

Black women in Chicago are prospering at home and in public. |

| If they feel that sting of race prejudice they seem to be confident of their own worth and hopeful for better conditions. One important evidence of progress is the enlargement and improvement of the home life of the Negro people. | If Black women in Chicago face racism, they do not allow it to affect them. |

| Ten or fifteen years ago they lived in districts of the city bordering on what may be called the “slums.” Vices of all kinds menaced the morals and health conditions of their families. But it is now easy to discern a great improvement in this respect. Better economic conditions have enabled them to purchase and occupy residences on some of the finest avenues and boulevards of the city. | In the last ten to fifteen years, living conditions for Black residents have improved from dangerous and unhealthy slums to homes on well-kept streets. |

| Fifty School Teachers It scarcely need be stated that in reference to employment in the trades, shops and stores Colored women are the least favored of any class of women in the city, yet it is impossible for them to be idle and respected. |

Most places of employment consider Black women to be the least desirable type of employee, but if Black women do not work they are looked down upon. |

| While only a few colored women are fortunate enough to gain positions in what are considered the higher callings, they are nevertheless industrious and increasingly willing to do whatever their hands find in order to earn a respectable living. | Black women work hard in whatever job they can obtain. |

| About fifty Colored women have won positions as teachers in our mixed public schools. There is also a surprising number of young women holding good positions as clerks and stenographers. One young woman through civil service examination secured an important position with the board of education in Chicago and is now private secretary to the assistant superintendent of schools. | Fifty Black women work as teachers in mixed-race schools. Other Black women work as clerks, stenographers, and office workers. |

| Young Colored women may also be found acting as assistants in dental offices, as court stenographers, as demonstrators of special goods in large department stores, as meat inspectors in stockyards, a few in canning and hair factories, a few as clerks, and scores of them earn a comfortable living as manicurists, chiropodists and hair culturists in private families. | Young Black women also work in dentist offices, courts, department stores, factories, and salons. |

| Many in Business. In addition to these there are a number of Colored women who have their own millinery establishments, beauty shops and dressmaking and costuming parlors that are elegantly appointed and up to date in every detail. |

Many Black women own their own businesses. |

| There is also an increasing number of professional nurses, several of them holding positions as nurses in the public schools and members of the Visiting Nurses’ Association. | The number of Black women working as nurses is increasing. |

| There are several Colored women connected with the juvenile court, acting as probation officers, and one adult probation officer. There are half a dozen Colored women physicians, three dentists and one practicing attorney. | Several Black women work in the juvenile court system. Some are doctors, dentists, and lawyers. |

| Eight or ten young Colored women are employed in the public library. There is a large number of music teachers, both vocal and instrumental. As a further evidence of progress young Colored women are eagerly crowding the night schools of the city in order to equip themselves for business positions. | Black women also work as librarians and teachers. Many also take classes at night in hopes of getting a better job. |

| Praise for Plain Women. A class of women that cannot be ignored in this story of the life of the Colored women of Chicago is the women who work with their hands in the humbler walks of life, as cooks, housecleaners, laundresses, caretakers and domestics. One of the most interesting sights in our public streets in the early morning hours is the large army of Colored women going in all directions to their day’s work. |

The majority of Black women workers work in the domestic sector as cooks, maids, laundresses, and nannies. |

| These women deserve great credit for their eager willingness to aid their husbands in helping to provide a living for themselves and their families. | Women in the domestic sector work very hard in the least desirable jobs. They deserve to be recognized for their work. |

| Another phase of the life of these Colored women is their passion for organization. There are clubs for the study of civics, social clubs to promote refinement of life, clubs for the care and protection of dependent children, religious organizations in the interest of churches, and a number of social settlements and secret societies. | Many Black women are involved in civic and social clubs that work to improve life for Chicago’s Black community. |

| The most important understanding among Colored women is the establishment of the Phyllis Wheatley Home. It was organized and incorporated some years ago for the purpose of giving shelter and protection to the young Colored women who wander into Chicago unacquainted with the snares and pitfalls of a great city. The home is a comfortable brick building, simply furnished, and offers a home for young women until they have secured employment and one to which they can appeal and find a welcome at any time. Mrs. L. A. Davis is the founder and promoter of this enterprise and is president of a progressive club of Colored women who look after and support this noble work. | The Phyllis Wheatley Home is organized by women and serves young Black women who have just arrived to Chicago and need help. |

| The Right to Vote. A new and important responsibility has come to Chicago women in the franchise. It is believed that this power granted to the women of the state of Illinois is going to lift Colored women to new importance as citizens. They appreciate what it means and are eagerly preparing themselves to do their whole duty. |

Illinois recently granted women the right to vote. This is a big responsibility and opportunity for Black women. |

| They believe that they now have an effective weapon within which to combat prejudice and discrimination of all kinds. There need be no anxiety as to the conduct of these newly made Colored citizens. They have had a large and varied experience in organizations, and we expect to see in them an exhibition of the best there is in the Colored race. This splendid extension of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments will make many things possible and open many avenues of progress that have heretofore been closed to Colored women. It is the hope of the leaders of the race that these new citizens will cultivate whatever is best in heart and mind that will enable them to meet the common tasks of life as well as the higher responsibility with confidence and hope. | Black women can use the vote to fight discrimination and promote the ideals of the Black community. |

“Fannie Barrier Williams Lauds Chicago Women,” Chicago Defender, October 10, 1914.

Background

Half a million Black Americans relocated from the South to the North between 1910 and 1920, part of a movement that is known as the Great Migration. Black Americans found life in the South increasingly dangerous. Lynching and other forms of racist violence terrorized communities. Despite public protests and individual campaigns, the horrific practice of lynching continued well into the mid-twentieth century. In addition, segregation limited access to jobs, education, housing, and voting rights. In the North, growing cities provided new opportunities. Many young Black women earned as much as a domestic worker in one day in the North as they did in one week in the South.

The Great Migration included many women, single and married. Although Black communities—like other racial and ethnic groups—believed that a women belonged at home, the percentage of Black families with at least one woman working was much higher than white or immigrant families. Black women were more likely to find full-time work than Black men. While work for Black men was frequently seasonal, the ongoing demand for domestic help led to more full-time opportunities for Black women. Although the vast majority of Black women were employed in domestic service, working as maids, cooks, laundresses, or nannies, some women were able to find other jobs, including factory work, nursing, and teaching.

Although life in the North provided better opportunities and saw less racial violence than the South, it was not without prejudice. Ongoing institutionalized racism ensured that certain neighborhoods excluded Black residents, schools in Black communities received unequal resources, and Black workers received the lowest wages. Women activists such as Fannie Barrier Williams, Adella Hunt Logan, and Mary Church Terrell helped Northern Black communities establish organizations and social services that improved life for all Black citizens.

About the Document

This article by Fannie Barrier Williams appeared in the Chicago Defender in 1914. The Chicago Defender was a Black-owned newspaper that covered national news relating to Black life in America. Although the newspaper had around 120,000 subscribers, historians estimate over 600,000 men and women across the country read the Defender weekly. In the South, multiple readers shared one copy in barbershops, bars, churches, and other community spaces. Articles promoted migration to Northern cities, presenting life in the North as a gateway to the American dream.

Fannie Barrier Williams was a speaker, writer, and activist in Chicago, Illinois. She spent her childhood in upstate New York where her family had been one of the only Black families in her town. When she took a teaching job in the South, she witnessed the horrors of Jim Crow racism firsthand. After marrying successful lawyer Samuel Laing Williams and relocating to Chicago, Williams dedicated her time to helping Black women leaving the South. She received letters from Southern mothers begging her to help find jobs for their daughters. Williams partnered with employers to find placements for young women. She also joined several organizations to further promote better housing, education, and social services for Black families.

Vocabulary

- domestic work: Paid work done in someone’s home, including cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children.

- Fifteenth Amendment: The constitutional amendment that declared the right to vote could not be denied on the basis of race, color, or previous condition of servitude; it was ratified in 1870.

- Fourteenth Amendment: The constitutional amendment that declared all citizens have equal protection under the law; it was ratified in 1868.

- idle: Bored or inactive.

- juvenile: A young person.

- laud: Praise and celebrate.

- lynching: The illegal execution of a person by a mob.

- millinery: A business that sells hats.

- probation officer: A person who works with individuals after they have been released from prison or completed their sentence.

- segregation: Separating people by race, class, gender, or ethnic group.

- stenographer: An office worker who takes notes in shorthand.

- vice: A moral failure or weakness.

Discussion Questions

- What are the types of jobs described in this article? What are the differences among these jobs?

- Who is Williams talking about when she praises women from “humbler walks of life?” Why does she single them out, and why is it important for us to know about them today?

- Williams ends this article by discussing woman suffrage. What is her argument and why does she believe suffrage is particularly important for Black women?

- Williams presents a generally positive view of life in Chicago. Why might she want to present this perspective?

- To what extent does Williams address the negative aspects of life for Black citizens in the North? What do you think of her assessment of these challenges?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 7.6: Word War I: Home Front

- Explore the ideas and actions of Black suffragists by reading Fannie Barrier Williams’s article in tandem with Adella Hunt Logan’s article in The Crisis, Mary Church Terrell‘s life story, and Ida B. Wells‘s life story.

- Compare the different types of waged work women took on in this era by combining this article with Lewis Hine’s photographs of industrial workers and the articles describing the El Paso laundry strike. Consider how race and geography had an influence on the types of work women did.

- Use this article in conjunction with the advertisement for electric household appliances to consider the experience of paid domestic workers in this era.

- Explore some of the reasons Black men and women migrated to the North by analyzing this article in combination with the photograph of Southern anti-suffragists, the NAACP testimony about Black women voting, the life story of Ida B. Wells, and additional materials in the Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow curriculum guide.

- Consider the many ways Black women fought to legitimize their citizenship and fight discrimination by studying this source alongside Adella Hunt Logan’s case for woman suffrage in The Crisis; the account of two Black social workers on the French front; the photograph of the 1917 silent march; the photograph of Atlanta Neighborhood Union; and the life stories of Mary Church Terrell, Madam C.J. Walker, Ida B. Wells, and Maggie Walker.

Themes

IMMIGRATION, MIGRATION, AND SETTLEMENT; WORK, LABOR, AND ECONOMY; POWER AND POLITICS

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For more about the Great Migration and Black experiences in this era, see Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow.