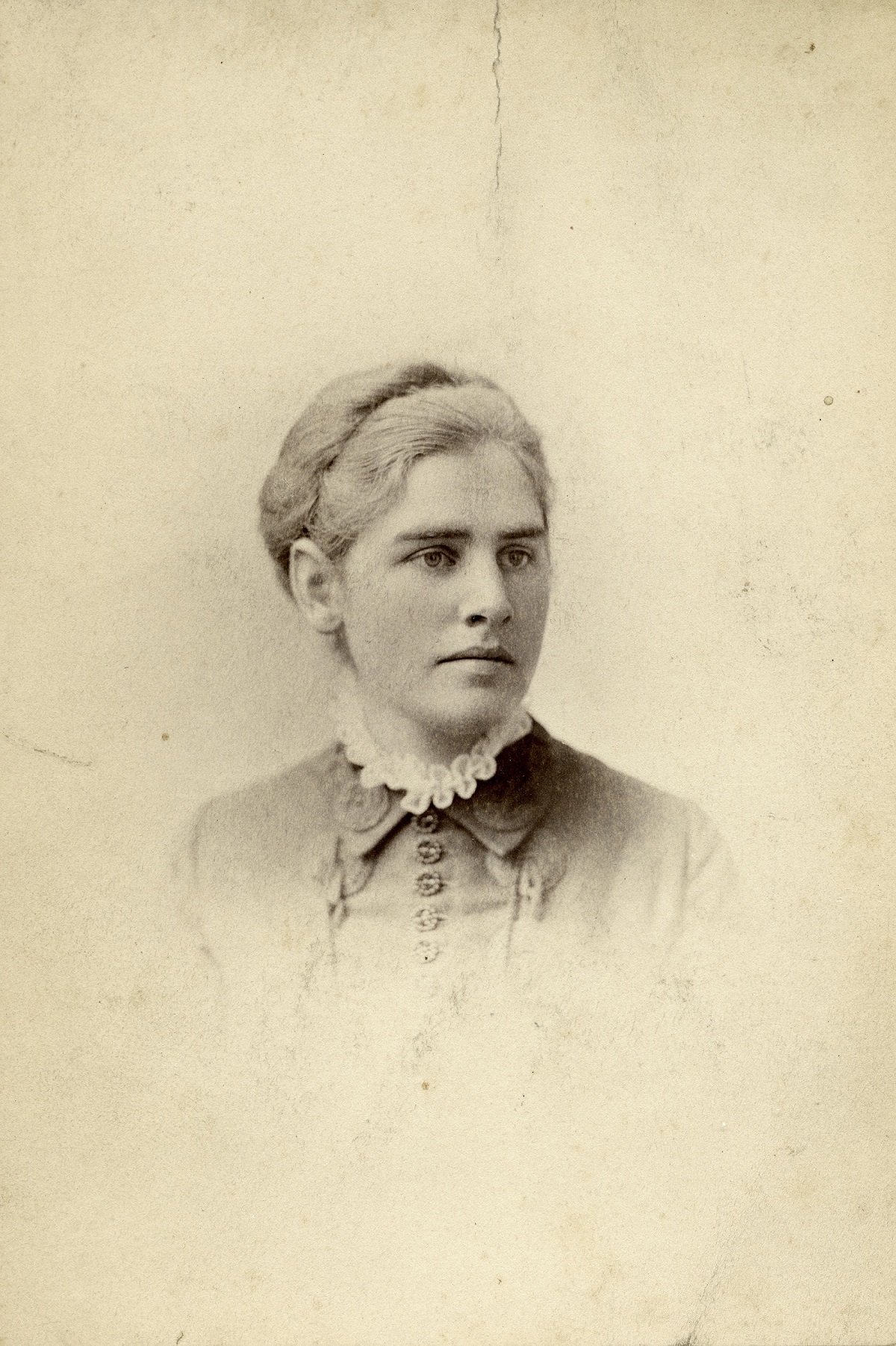

Katharine Coman was born on November 23, 1857, in Newark, Ohio. She grew up on a farm with six siblings. Her parents believed that education was as important for their daughters as for their sons.

In 1880, Coman graduated from the University of Michigan. One of her professors recommended her to Wellesley College, a women’s college in Massachusetts. There, Katherine took a job as a rhetoric professor. After one year, she switched to teaching history.

Coman loved teaching. She specialized in the history of economics and focused her research on industrial history. She saw how industrialization was changing American society and believed it was important to understand and discuss these changes.

Her work led to an interest in social activism, focusing on working conditions in factories and living conditions in cities. In 1890, she spent her summer at Hull House in Chicago, one of the most famous settlement houses in the country. She befriended social activist and Hull House founder Jane Addams and met women workers who went on strike for better working conditions. Coman became their spokesperson and wrote about their living and working conditions in a pamphlet she distributed.

While at Wellesley, Katharine Coman met Katharine Lee Bates. Bates was an English professor, writer, and poet. The two Katherines became very close. By 1890, they were in a romantic relationship. At the time, it was not socially acceptable for same-sex couples to live openly. While there is no specific evidence of their physical relationship, it is clear they at least shared a deep romantic connection. While Bates studied at Oxford University in England for a year, she wrote in a letter to Coman:

“For I am coming back to you, my Dearest, whether I come back to Wellesley or not. You are always in my heart and in my longings. I’ve been so homesick for you on this side of the ocean and yet so still and happy in the memory and consciousness of you.”

While Bates studied in England in 1891, Coman devoted more time to social activism. After seeing the working conditions of immigrant women in garment factories, she opened her own garment factory with better working conditions. Factories typically bribed clothing sellers to receive better-paying orders. Coman refused to participate in bribery. Consequently, she did not receive enough orders to keep her business running. The factory closed after only six short weeks.

Coman continued her social activism after the failure of her garment business. The following year, she opened a settlement house in Boston with Bates and their friend Vida Scudder, an English professor at Wellesley. Coman was the most involved of the three with the organization, which they called Denison House. It was a community center and home for female college students who wanted to pursue social and activist work in immigrant communities.

While she devoted much of her time to social activism, Coman also loved her work as a professor. She was an excellent teacher and researcher. In 1894, she published her first book, The Growth of the English Nation.

When Coman and Bates returned to Wellesley from their summer travels to Oxford in 1894, they moved in together for the first time. They rented a house with Charlotte Finch Roberts, a chemistry professor at Wellesley. The three women lived together for four years.

Coman loved teaching. She specialized in the history of economics and focused her research on industrial history.

In 1895, the dean of the University of Michigan offered Katharine Coman the position of dean of women. She declined the offer, stating that she wanted to continue to spend most of her time teaching. Her relationship with Bates likely played a role in this decision as well. They would have had to live in separate states.

Coman believed that economics was important and that female college students should have the opportunity to study it. When she was the acting dean of Wellesley between 1899 and 1900, she established a department of economics and became its first department head.

Coman and Bates often spent time apart. Both women frequently traveled for long periods to study or conduct research. In 1900, they rented a home together. Katharine Coman purchased the home several years later. In 1907, they bought and designed their own house together.

Households made up of two women who supported each other financially were common at this time, especially at women’s colleges. Many people often described them as “Boston marriages.” The term was a reference to the novel The Bostonians by Henry James, which was published in 1886. Two female characters in the novel lived in this type of arrangement. Women in such relationships were typically college-educated and financially independent. It was still expected that women would marry men and have children, but these same-sex relationships between independent professional women were socially accepted. While not every so-called “Boston Marriage” was romantic, many of them were and would be considered lesbian relationships today.

Coman’s area of expertise, Industrial history, was a new field of study. When she published The Industrial History of the United States in 1905, it was the first major book on the topic. It became a popular textbook, but many people criticized it for its superficial study of the American West.

In response to the criticism, Coman traveled to the West to conduct more research. Even though she was sympathetic to the negative effects of industrialization on Indigenous communities, Coman’s perspective was influenced by social Darwinism. In an article about contract labor in Hawai’i, she referred to Indigenous people as “primitive” and described the American takeover of the kingdom as “never gentler or less destructive of native economy.”

Through her studies in the West, Coman became increasingly concerned about the effects of industrialization on nature. When The Industrial History of the United States was reprinted in 1910, she included a chapter on the exploitation of natural resources. She even taught a class at Wellesley about the topic.

In 1912, doctors discovered that Coman had a tumor in her breast. She had surgery to have the tumor removed and eventually had a mastectomy. Unfortunately, cancer treatments were limited and the tumor was probably discovered too late. Bates supported Coman during her illness for the next several years in the home they shared.

Katharine Coman died on January 11, 1915. She was 58 years old. In the days following her death, Bates wrote a tribute to Coman, which she shared with close friends and family. Bates published Yellow Clover: A Book of Remembrance in 1922. It is a book of poems about Coman and her illness. During their relationship, the women sent each other yellow clovers as love tokens.

Vocabulary

- mastectomy: Surgery to remove a person’s breasts, usually to prevent cancer from spreading.

- pamphlet: Small booklet with information about a certain topic.

- rhetoric: The art of speaking.

- settlement houses: Organizations that provided a range of social services to the local community and were typically found in poor urban areas.

- Social Darwinism: The belief that people of certain races and ethnicities are better than others.

Discussion Questions

- How did Katherine Coman’s career as a professor and researcher influence her social activism?

- What opportunities did women’s colleges provide their female students and professors?

- Describe the relationship between Katharine Coman and Katharine Lee Bates. Why is it important to explore this part of Katharine Coman’s life?

Suggested Activities

- Pair this life story with the life story of Jane Addams. How did these two women affect the lives of working-class women?

- Katharine Coman unsuccessfully opened a garment factory to create better working conditions for women. Consider the conditions she was trying to improve by combining this life story with a report about factory work.

- Explore the effects of American expansion and industrialization on the western United States. Combine this life story with the diary of an Arizona teacher and the life story of Mary Ellen Pleasant.

- Consider another perspective on the imperialism and industrialization of Hawai’i by pairing this life story with the life story of Queen Lili’uokalani.

- Include this life story in a lesson about female same-sex relationships throughout history. Combine this life story with those of Bessie Smith, Antonia Pantoja, Angela Davis, and Billie Jean King.

- As an educated woman, Katharine Coman used her scholarship to help working-class women. Combine her life story with the life stories of Leonora Barry and Florence Merriam Bailey. How did these women use their scholarship in activism? What biases did they have in doing this work?

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE