Document Text |

Summary |

| The Minneapolis “Slave” Case.

The Democrats have been as unfortunate in their attempt to make capital out of the case of Eliza Wonston as they were in that of Henry Sparks. After all their charges that Eliza was Persuaded to leave her master by “Abolitionists;” after the dirt-eaters of St. Anthony and Minneapolis, headed by McLean of the Winslow House, had offered indignities and threatened violence to the person of Mr. Babbitt and others, it turned out that Eliza, when she left Mississippi, was fully determined to assert her freedom as soon as she reached the free soil of Minnesota. If there is any shame left in these miserable toadies, we should think they would not now dare to look an honest freeman in the face. |

The Democrats have been trying to make a big deal out of Eliza Winston’s case. They said abolitionists persuaded her to seek her freedom. They threatened violence in retaliation. But Eliza was always determined to claim her freedom as soon as she got to Minnesota. |

| We have before us an extra from the office of the Minneapolis Atlas, giving the full facts of the whole case. From this it appears that non citizens of Minnesota, from first to last, had any agency whatsoever in prompting the woman to assert her rights. It was her own idea possessed before she left Mississippi, to assert and secure her rights in Minnesota, unless her master would give her free papers, which he refused to do. Having thus determined, she applied for aid, when it became apparent to her that she would be compelled to resort to our courts to secure and maintain her liberty. After having satisfied themselves that the woman was anxious and determined to get her liberty if possible, Messrs. Babbitt and Bigelow, applied to Judge Vanderburgh for a writ commanding the Sheriff to bring her before him, in order that the facts in the case might be inquired into. The writ was served, the woman brought into Court, and there informed that she was free to go where and with whom she chose. | The following is an article from the Minneapolis Atlas newspaper that gives all the facts of the case. It proves that no citizens of Minnesota encouraged Eliza to claim her freedom. She had the idea before she left Mississippi. She asked her enslaver for her free papers when she arrived in Minnesota. When he refused, she asked for help so she could take her case to court. Two men interviewed her, and when they learned how serious she was they took her case to court, where she won her freedom. |

| The following affidavit of Eliza gives the full particulars as to the manner in which she became free. We bespeak a careful reading of it b men of all parties:

STATE OF MINNESOTA, Hennepin County. ELIZA WINSTON being duly swoon, deposes and says: My name is Eliza Winston, am 30 years old. I was held as a slave of Mr. Gholdson of Memphis, Tennessee, having been raised by Mr. Macklemo, father-in-law of Mr. Gholson. I Married a free man of color who hired my time of my master, who promised me my freedom upon the payment of $1,000. My husband and myself worked hard and he invested our savings in a house and lot in Memphis, which was held for us in Mr. Gholson’s name. This house was rented for $8 per month. My husband by request, went out with a company of emancipated slaves to Liberia, and was to stay two years. He went out with them because he was used to traveling, and it was necessary to have some one to assist and take care of them. When he returned, my master was to take our house and give me my free papers, my husband paying the balance due, in money. My husband died in Liberia, and my master Mr Gholson got badly broken up in money matters, and having pawned me to Col. Christmas for $800, died before he could redeem me. I was never sold. I have always been faithful and no master that I ever had has found fault with me. Mr. Macklemo, my first master, always treated me kindly and has tried to buy me off Col. Christma, a good many times. When Mr. Gholson married Mr. Macklemo’s daughter, I went with my young mistress. |

I am Eliza Winston, and I am 30 years old. I was enslaved by Mr. Gholson of Memphis, Tennessee. I married a free Black man. Mr. Gholson promised to grant my freedom if we paid him $1,000. We worked hard to make the money, and bought a house that Mr. Gholson managed for us. My husband went to Liberia to help some recently emancipated people settle there. My husband died in Liberia. Mr. Gholson had money troubles, so he pawned me to another enslaver named Colonel Christmas for $800. He died before he could free me properly. I was never sold. I have always been faithful, and no enslaver has even complained about me. |

| I became the slave of Mr. Christmas 7 years ago last March. They have often told me I should have my freedom and they at last promised me that I should have my free papers when their child was seven years old. Thuis time came soon after we left home to come to Minnesota. I had not much confidence that they would keep their promise for my mistress has always been feeble and she would not be willing to let me go. But I had heard that I should be free by coming to the North, and I had with my colored friends made all the preparations which we thought necessary. I had got a little money and spent it on clothes, my colored friends gave me some good clothing, and I came away with a good supply of clothing in my trunk. Sufficient to last me two year and of a kind suitable to what we supposed this climate would be. The trunk containing this clothing was left at the Winslow House when we went to Mrs. Thornton’s, I taking only one calico dress, besides an old washing dress. | I’ve been enslaved by Mr. Christmas for seven years. He told me I would get my free papers when his child turned seven. But I didn’t believe them because my mistress was always sick and would not want to let me go. He made plans to move to Minnesota. I heard that Minnesota was a free state. I made plans to secure my own freedom when I got here. My friends helped me collect clothing. But this clothing was left behind by my enslavers during our journey. |

| After I got to St. Anthony, I got acquainted with a colored person and asked her if there were any persons who would help me in getting freedom. I told her my whole story and she promised to speak with some persons about it. She did so, and a white lady living near met me a the residence of my colored friend. I also told her my story, and she told me there were those who would receive me and protect me. | When I got to St. Anthony, Minnesota, I asked a Black woman if there was anyone who could help me get my freedom. She introduced me to a white lady who said there were people who could help me. |

| I thought I had a right to my clothes because they did not come from my master or mistress, and I purposed to carry away at different times when I should not be suspected, some portion of them. I fixed upon the coming Sunday whenI would leave my master, but before thee time came Col. Christmas and his family went out to Mrs. Thornton’s and, as I understood, were not coming back to the Winslow House to stay any more, I thought some one of the servants had made my master suspicious, and that he went away on that account. | I thought I had the right to my clothing, since my enslaver did not buy it. But I think my enslaver realized I was trying to get my freedom. He moved to a new house, and left my clothing behind. |

| On the day I was taken by the officer, some men came out to Mrs. Thornton’s and I heard them tell them that persons were coming out to carry me off.

So whenever any one was seen coming, my mistress would send me into the woods at the back of the house. I minded her, but I did not go very far, hoping that they would find me. I was sent into the woods several times during the day, as was the case, at the time when the party came who took me away. I had on my washing dress and I went in to change it before going with the officer. My mistress asked me why I went off in this way; she said she would give me free papers; I asked her why she did not in St. Louis. She said over again and again that I must not go in this way, but that they would give me my free papers. |

On the day an officer took me, some men came out to the place where we were staying. I overheard them say that some people were coming to take me away.

So whenever anyone came to the house, my enslaver would send me to the woods so they could not find me. I did not go very far, hoping they would see me. I was sent into the woods many times before the officer came to get me. I changed into better clothing before leaving with the officer. My enslaver asked why I was going with the officer. She said she would give me free papers. I asked her why she hadn’t already given them to me. She kept saying I should not leave with the officer. |

| I told her I had rather go now. When my master came into the court room he came up to me and gave ten dollar.–when I was told I was free my master asked me if I would go with him, and told me not to do wrong. I told him that I was not going to do wrong, but that I did not wish to go with him. I have been Col. Christmas’ slave for more than seven years, and I have always been faithful to him and done my best to please him and my mistress. The latter has always been feeble, and I have waited upon her and taken care of her and the child. During all this time owing to the poor health of my mistress, I have been closely confined, have had scarcely any time to myself or to see the other slave, as most house servants can have, but I have never fretted or complained, because I thought I I did my very best they would, perhaps, give me my freedom. | I told her I wanted to go. When my enslaver came to court, he gave me ten dollars. When the judge said I was free, my enslaver told me to go back to his home with him. I said no. I was his slave for seven years. I always did my best. I thought they would give me my freedom if I never complained. |

| Since my husband died I might have married very happily with a free colored person, but Col. Christmas would not let me marry any one but one of his plantation hands, and I would not marry any but a free person. I thought if I could not better myself by marrying I would not marry at all, and I knew it would be worse for me if I married a slave. I wanted my master to give me free papers so that I could go back to Memphis where I could get employment as a nurse girl, and could earn from ten to fifteen dollars a month, and could marry there as I desire to do, but I despaired of getting my freedom in this way, and although I am sorry I must sacrifice so much, still I feel that if I cannot have my freedom without, I am ready to make the sacrifice. | I could have married another free Black man after my husband died, but Mr. Christmas would only let me marry one of his other enslaved people. I thought this would make life harder for me, so I refused. I wanted my free papers so I could work in Memphis, Tennessee as a nurse. I could make money and marry who I wanted. But I soon realized that Mr. Christmas would never give me my freedom. I’m sorry I had to do things this way, but it is worth the sacrifice. |

| I will say, also, that I have never received one cent from my property at Memphis since my husband died.

It was my own free choice and purpose to obtain my freedom, and I applied to my colored friend in St. Anthony, without solicitation on the part of any other person. I have nursed and taken care of the child of my mistress from her birth till the present, and I am so attached to the child that I would be willing to serve Col. Christmas if I could be so assured of my freedom eventually, but with all my attachment to the child, I prefer freedom in Minnesota, to life-long slavery in Mississippi. Her mark. Eliza Whiston |

I have never been paid for the property my husband bought.

I made my own choice to pursue my freedom. I love the baby I take care of, and if I knew they would someday give me freedom I would stay with them. But I prefer freedom in Minnesota to life-long slavery in Mississippi. |

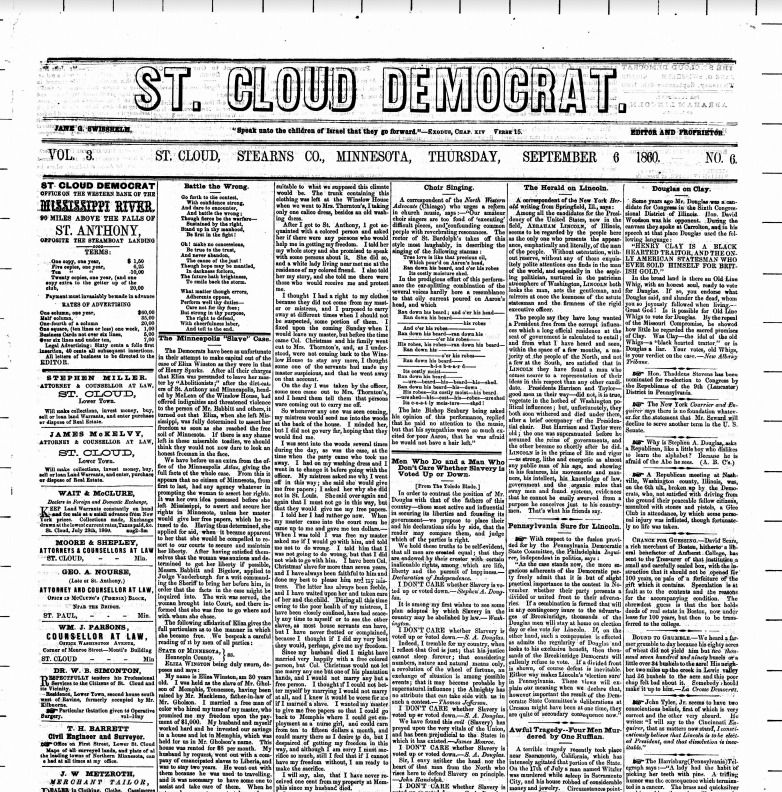

“The Minneapolis Slave Case,” St. Cloud Democrat, September 6, 1860, pg 1. Minnesota Historical Society.

Background

In 1860, the western states and territories of the United States were a checkerboard of conflicting laws and social customs governing the practice of slavery. In some of the states and territories, slavery was fully legal, explicitly written into the laws and state constitutions. Some so-called free states and territories outlawed the practice of slavery but had legal loopholes that allowed the continued exploitation of Black people. Other states and territories declared slavery illegal but allowed enslavers to bring enslaved people to their lands without challenging them. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and the Dred Scott decision of 1858, this was the case across the country.

Minnesota fell into the last category. Enslaved people had lived and worked in Minnesota since it was a territory. When Minnesota became a state, the state constitution clearly barred slavery. But many people in Minnesota made their living from providing services to vacationing enslavers who visited during the summer months. As a result, state authorities did not challenge enslavers who brought enslaved people with them on vacation. This contradiction created an opportunity for enslaved people who wanted to self-emancipate.

About the Document

In this newspaper article, free woman Eliza Winston explains how she made a plan to self-emancipate while traveling with her enslavers in Minnesota. The opening of the article explains that some people in Minnesota believed that local abolitionists convinced Eliza to leave her enslavers. But Eliza’s testimony makes clear that she acted independently in her own best interests. The article also provides important details about Eliza’s life as an enslaved person in Mississippi.

Vocabulary

- abolitionist: A person who worked to end the practice of slavery.

- self-emancipate: When an enslaved person freed themselves.

Discussion Questions

- Why was Eliza Winston able to self-emancipate in Minnesota during her enslavers’ vacation?

- How did the people of Minnesota respond to the outcome of Eliza Winston’s case?

- What does Eliza Winston’s testimony teach us about the agency of enslaved people in the U.S.?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 4.12 African Americans in the Early Republic

- Use this document to teach students about the agency of enslaved Black people on the eve of the American Civil War.

- The decision in Eliza Winston’s self-emancipation case directly contradicted the Supreme Court ruling of Scott v. Sanford. After studying Eliza’s story, ask students to read the life story of Harriet Robinson Scott and discuss how complicated the legality of slavery in the U.S. had become on the eve of the Civil War.

- To learn more about the lives of Black Americans in the West, see:

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE