Afong Moy

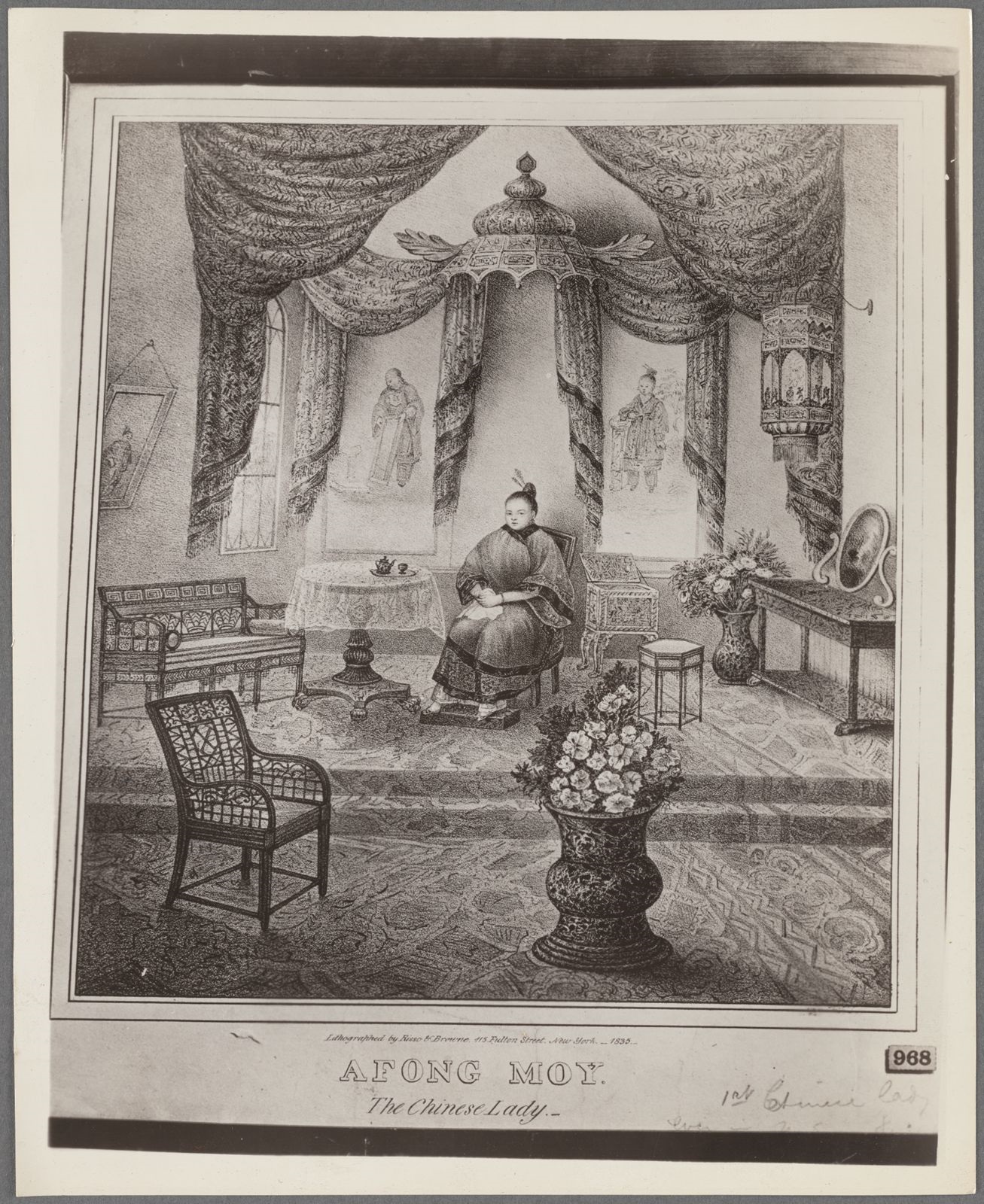

“Afong Moy. The Chinese lady” The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

In the spring of 1834, Captain Benjamin Obear paid a large sum of money for permission to bring an 18-year-old Chinese woman called Afong Moy to the U.S. He believed Afong would help him sell Chinese goods to American citizens. Afong’s tour was expected to last two years. We do not know if Afong had any say in the decision that would change her life.

Afong set sail from Guangzhou, China, traveling south along the Pearl River before crossing the Pacific Ocean to Indonesia. Next, she crossed the Indian Ocean before traveling around the southern tip of Africa. The final leg of her journey was crossing the Atlantic Ocean to reach New York City. The trip took about six months, and Afong probably endured bad food, dangerous weather, and hours of boredom.

When Afong finally arrived in New York City in October of 1834, she was the first recorded Chinese woman to visit the United States. Her arrival caused a big stir. Just a few weeks later, Benjamin put Afong to work. He made her the centerpiece of an exhibition of Chinese goods, hoping that her novelty would attract curious shoppers. Her early appearances were staged inside Benjamin’s home. Afong was seated in a throne-like chair in the center of the room. She was dressed in traditional Chinese clothing, and her feet were prominently displayed on a stool in front of her. An assortment of Chinese antiques and goods were artfully arranged around her. Visitors paid 50 cents to see the scene and were encouraged to ask her questions about her life in China. An interpreter was provided to assist with these exchanges.

Afong’s exhibition was a huge hit. She represented a country and culture that was completely foreign to most Americans, so thousands paid to see her. Even Vice President Martin Van Buren stopped by. Afong’s exhibition sparked a fad in Chinese goods and fashions, just like Benjamin had hoped. But the scene staged by Benjamin sent a very clear message: Afong was a commodity like the objects arranged around her. Her visitors did not see her as entirely human, and this resulted in a general attitude of disrespect. For example, it is likely that Afong Moy was not her given name, but rather a nickname used by Benjamin because it was easier than properly pronouncing her full name. But local newspaper accounts did not even respect her nickname. “Miss Julie Foochee-ching-chang-king,” “Madame Ching Chang Foo,” and “Miss Keo-O-Kwang King” were some of the many names newspapers made up to announce Afong’s arrival in the city. These racist names contributed to Afong’s dehumanization.

Afong was the centerpiece of an exhibition of Chinese goods.

What fascinated visitors the most were Afong’s bound feet. Foot binding was a Chinese cultural practice that dated back to the 900s. Mothers would break the toes of young girls and wrap their feet in such a way that the bones arched over time. By the time a girl reached adulthood, her feet might be only three inches long. Foot binding served many cultural functions in China in the 1800s. It was considered a mark of beauty and refinement. Bound feet made it very difficult for women to walk, so families that bound their daughters’ feet were telling the world that they did not need their daughters to work. Many Chinese women had a complicated relationship with their bound feet. They were very painful and required constant care and attention to prevent injury or infection. But they were also a symbol of a woman’s social standing and her value to her family and community.

The American audiences who visited Afong did not understand any of this cultural context. They were simply shocked when they saw how tiny Afong’s feet were, and then equal parts horrified and titillated when they learned about the practice of binding. Visitors took Afong’s bound feet as further proof that she was not quite human. They also took it as a sign that Chinese culture was inferior to American culture.

Visitors found other things to criticize about Afong. They thought the Chinese government, led by the emperor, was backward compared to American democracy. They called her unintelligent, failing to acknowledge that English was not her first language. In this way, Afong’s appearances laid the foundation of the anti-Chinese sentiment that would explode over the course of the 1800s.

In January 1835, Benjamin took Afong’s exhibition on tour. In Philadelphia, she was exhibited in a museum, further reinforcing the public perception that she was an object and not a person. While in Philadelphia, Afong was forced to allow eight white doctors to examine her feet. In Chinese culture, this was a terrible violation of privacy. This moment demonstrates that Afong had no control over what happened to her. In March, Afong traveled to Washington, D.C., where she was presented to President Andrew Jackson. This was the first time a U.S. president met a Chinese person while in office. But Afong was not there as a diplomat. She was a curiosity. This episode further reinforced the public’s impression that Chinese people were not equal to white Americans.

Afong visited Baltimore, Maryland, and Charleston, South Carolina, before returning to New York City in June 1835. At some point during her tour, Benjamin stopped traveling with her and put her in the care of a manager named Henry Hannington. Henry oversaw Afong’s transformation from a woman who was promoting the sale of Chinese goods to an attraction in her own right. He made her display her unbound feet for the public, further violating her privacy, and encouraged her to sing for audiences. After presenting Afong at the American Museum of Natural History, in the summer of 1835, Henry took Afong on a whirlwind tour of New England followed immediately by a tour of Cuba and the American South. She was exhibited in Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. She likely also visited Tennessee, Missouri, and Kentucky before reaching Ohio, and her final known exhibition took place in Pennsylvania. In six months, Afong traveled 1,000 miles and encountered many iterations of American society.

At this point, Afong’s handlers should have been making plans to return her to China because her contracted time was nearly up. But a fire wiped out the fortunes of the merchants who had sponsored her trip, and they decided to keep her indefinitely to make up for their losses. Henry featured her in a series of entertainments until he went bankrupt in 1837. By this point Benjamin and Augusta had disappeared from New York society, and the merchants who had originally funded Afong’s journey to the U.S. were long gone. She had no money because she had never been paid for her work, so she had no way to make it back to China. She spent some time in a poorhouse in New Jersey before someone took her in in exchange for money from the state. Afong lived there for the next eight years.

In 1847, Afong began to tour the U.S. once more under the management of the legendary showman P. T. Barnum. During this tour, Afong knew enough English to interact with her audiences directly. But within a few years, Barnum replaced Afong with a new, younger, Chinese lady called Pwan-Ye-Koo. Afong’s last public exhibition took place on February 21, 1851, and then she disappears completely from public record. There is so much that is unknown about Afong Moy, because she left no personal account of her experiences. But her brief time in the spotlight profoundly shaped U.S. attitude towards Chinese people at a critical moment in American history.

Vocabulary

Discussion Questions

- How was Afong Moy exploited for the benefit of white Americans?

- What does this story reveal about the history of U.S. attitudes toward Asian Americans?

- Why is it important to know Afong Moy’s story?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 4.4 America on the World Stage

- American audiences believed that Afong Moy was uneducated because she had difficulty communicating in English, but she was probably one of the most well-traveled people in the United States in her time. Ask students to trace Afong Moy’s journey on a world map and calculate the miles she traveled. Then ask students to research one of the places she visited and share with the class what kind of society and culture she would have encountered there.

- Afong Moy and Maria Gertudis Barceló were two public figures who Americans used to justify their racist attitudes towards non-white people. Ask students to read both of their life stories and then write a short reflection about how damaging negative stereotypes can be formed from simple cultural misunderstandings.

- For a larger lesson about American attitude toward Chinese women in the 1800s, teach this life story together with the following:

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

To learn more about the history of the Chinese in America, see Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion