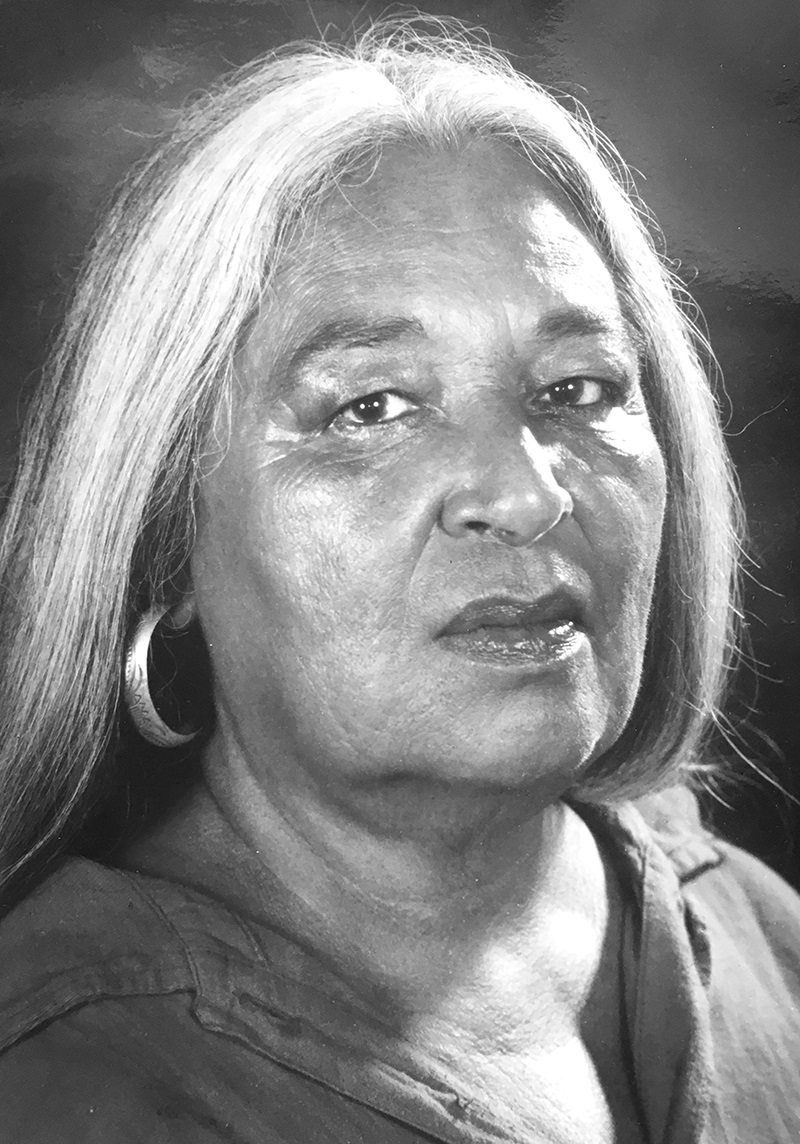

Patricia Ann McGillis was born on January 21, 1928, in Pocatello, Idaho, on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. Her Lakota name, Tawacin WasteWin, means “compassionate woman.” Her father, John, worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and her mother, Eva, worked as a nurse in the Indian Health Service (IHS). Patricia’s only sister, Frances, was born when Patricia was almost three years old.

Patricia was independent from a young age. When she was six years old, she won a local interpretive dance competition, which allowed her to participate in the national competition in Chicago. Eva took her to the event, which was the first time Patricia visited a big city. Patricia wanted to explore the city and sneaked out of the hotel by herself. Unable to find her way back, she hailed a cab, and the cab driver returned her to the hotel.

The family often had to move for her father’s job with the BIA. Her parents raised Patricia in the Catholic faith, but also instilled their traditional Lakota values and traditions in her and Frances. John and Eva believed it was important that their daughters learned how to thrive in white American society in addition to Lakota culture. One year, they encouraged Patricia to read every book in the school library, fostering a lifelong love for learning in her. Their maternal grandfather often lived with the family and told the girls traditional Lakota stories.

Even at a young age, Patricia faced racial discrimination. When the family lived in Arizona, she and her sister went to see a movie, and the movie theater required them to sit in the back because of their Indigenous heritage. They were not able to see over the heads of the people in front of them. When they told their mother, Eva returned to the movie theater and threatened to have the entire Indigenous community boycott them if they treated her daughters like that again.

Patricia’s father retired from the BIA when Patricia was in high school, and the family moved to Alhambra, California. She enrolled in college. After briefly attending John Muir College, Patricia transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). She was the only Indigenous student at UCLA. Patricia often said she was Hawaiian to get access to spaces where Indigenous people were not welcomed. She graduated from UCLA in 1951.

Patricia wanted to become a teacher and earned her teaching certificate shortly after graduating from college. She took her first position at a school in Long Beach, California, that primarily served an Indigenous community. She was disappointed to see that the curriculum was not designed with Indigenous values in mind.

After teaching for one year, Patricia left her position. She married Charles Edward Locke III, who went by Ned. They had met at UCLA. She gave birth to their first daughter, who tragically passed away shortly after she was born. Patricia and Ned had two more children, Kevin and Winona.

Ned worked for a defense contractor, and the family moved to Anchorage, Alaska, for his job in 1966. This was a difficult time for Patricia. Her relationship with Ned deteriorated, and they eventually divorced.

Patricia noticed that the Indigenous Alaskans who moved to Anchorage struggled to adjust to life in the city. She founded the Anchorage Native Welcome Center in 1967 to help them adjust. It was her first full-time job since teaching after college and she loved helping people. She also became active in the Indigenous rights movement.

Her work in Anchorage led to a new job with the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE), and Patricia and her children moved to Boulder, Colorado. In her new role, Patricia helped establish colleges for Indigenous students. This work fueled her activism for Indigenous rights. Recalling her year as a teacher, she believed that tribes needed to control their own schools in order to provide Indigenous students with the education that best met their needs. By 1972, there were six tribal colleges in the United States.

To obtain funding for WICHE, Patricia lobbied Congress. At first, Patricia found that there was little support for Indigenous communities among members of Congress. Patricia changed the situation by working with people who had access to Congress members. Patricia and these individuals made appointments together with some of the representatives’ constituents. Instead of asking politicians for favors, Patricia would calmly tell them what they would do for their constituents. Congress passed the Tribally Controlled College or University Assistance Act in 1978, which provided educational grants for tribal colleges.

“We have to let the wisdom of the past . . . guide us and give us direction. We also have to have the means to cope with this modern world.”

Many tribal leaders were uninterested in establishing tribal colleges in their community. Patricia traveled to meet with them and explain the importance of education and Indigenous control over the curriculum. She believed that preserving the language and culture of their people was the only way to preserve their traditions.

Patricia’s work focused on Indigenous education, but she also advocated for other Indigenous rights. She contributed to the language of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which passed in 1978. It guaranteed Indigenous people the right to practice their religion and access sacred lands. Because of her advocacy for Indigenous rights, she was appointed to the Interior Department Task Force on Indian Education Policies in 1979.

In 1983, Patricia left Colorado and moved to Mobridge, South Dakota, near the Standing Rock Reservation where her mother grew up within the Lakota community. She left her position at WICHE and worked as a freelance consultant. She moved to the reservation itself in 1987, when her son bought a house there for his family.

Living on the Standing Rock Reservation fulfilled a lifelong dream for Patricia. It increased her passion to preserve Lakota culture and language by teaching Indigenous children. She took on several leadership roles with educational organizations on the reservation.

In 1991, Patricia received a MacArthur Fellowship, known as a “genius grant,” in honor of her work to save Indigenous languages, many of which were becoming extinct.

Patricia Locke died from heart failure on October 20, 2001.

Vocabulary

- reservation: Public land set aside for a specific use. Indian Reservations were areas identified by the federal government for the Indigenous community.

- United States Bureau of Indian Affairs: An agency of the federal government that oversees all issues related to the Indigenous community.

Discussion Questions

- How did Patricia Locke fight for the rights of Indigenous people?

- What role did education have in Patricia Locke’s activism? What does her work say about the importance of access to education for Indigenous communities?

- What does Patricia Locke’s story tell us about the American government’s treatment of Indigenous people?

- Based on Patricia Locke’s story, how has the position of Indigenous people changed since she was a child? What challenges to Indigenous communities still face today?

Suggested Activities

- Pair this life story with the life stories of Wilma Mankiller and Grace Thorpe. How did these three women stand up for their Indigenous communities?

- Consider the struggle for Indigenous rights in education by combining this life story with photographs of girls at Indigenous boarding schools and the life story of Zitkala-Sa.

- For a broader lesson on Indigenous activism in the 20th century, combine this resource with the occupation of Alcatraz, Women of All Red Nations (WARN), and the life stories of Wilma Mankiller and Grace Thorpe.

- For a larger lesson on women and activism during this period, teach this resource alongside documents restricting reproductive rights, anti-LGBTQ+ activism, Latina environmental activists, the anti-nuclear movement, disability rights, Take Back the Night, and the life stories of Byllye Avery, and Yuri Kochiyama.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; AMERICAN CULTURE; AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP