A Columbian Patriot, Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State conventions.

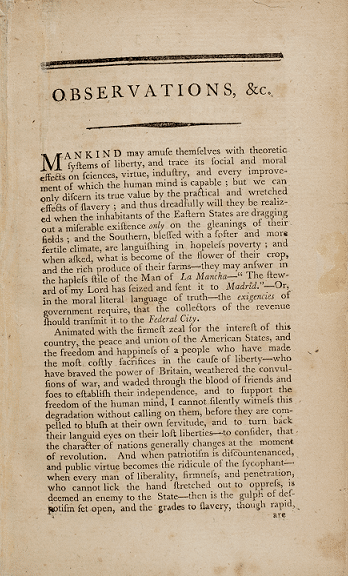

Mercy Otis Warren, “A Columbian Patriot”, “Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State conventions.” Pamphlets on the Constitution of the United States, published during its discussion by the people, 1787-1788 (Brooklyn, NY: 1888). New-York Historical Society Library.

Document Text |

Summary |

| There is no security in the proffered system, either for the rights of conscience or the liberty of the Press: Despotism usually while it is gaining ground, will suffer men to think, say, or write what they please; but when once established, if it is thought necessary to subserve the purposes, of arbitrary power, the most unjust restrictions may take place in the first instance, and an imprimatur on the Press in the next, may silence the complaints, and forbid the most decent remonstrances of an injured and oppressed people. | This Constitution does not do enough to protect the rights of citizens or the press. Dictators pretend to allow freedom of speech while they are gaining power. But once they have the power, they will pass laws that forbid the people to speak out against them. |

Mercy Otis Warren, “A Columbian Patriot”, “Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State conventions.” Pamphlets on the Constitution of the United States, published during its discussion by the people, 1787-1788 (Brooklyn, NY: 1888). New-York Historical Society Library.

Document Text |

Summary |

| He who violently or insidiously destroys the unquestionably necessary series of subordination, who produces the various classes of mankind as usurpers on those orders, which, in the seale of being, take rank above them, must inevitably throw a nation or a state into strong convulsions; nor, will reason authorize such an attempt, save in the last extremity. When the officers of government are chosen—when they are legally inaugurated, and have, in due form, taken their appropriate places, I am free to confess that I adopt, in an unqualified sense, the sentiment which Homer hath put into the mouth of his Pylian sage; and, at least until a succeeding election, I would say, “Be silent, friends, and think not here allow’d “That worst of tyrants, an usurping Crowd.” |

Any person who tries to destroy the divisions between social classes will throw their country into chaos. No reasonable person would allow such a thing to happen. Every time a new group of elected officials takes office, I am grateful that we are once again free from having to worry about the lower classes trying to take over, at least until the next election. |

| I confess that a Federal representative Republic is the government of my election, and under the constitution of the United States of Columbia I would choose to pass my days; yet, I possess no right to impose my sentiments on my brethren; nor can I be justified in flashing the lie in his face, who would maintain opposite principles. | A federal representative republic is the constitutional government of the US, and I choose to live under it. I cannot force my ideas on other people, even if those people are wrong. |

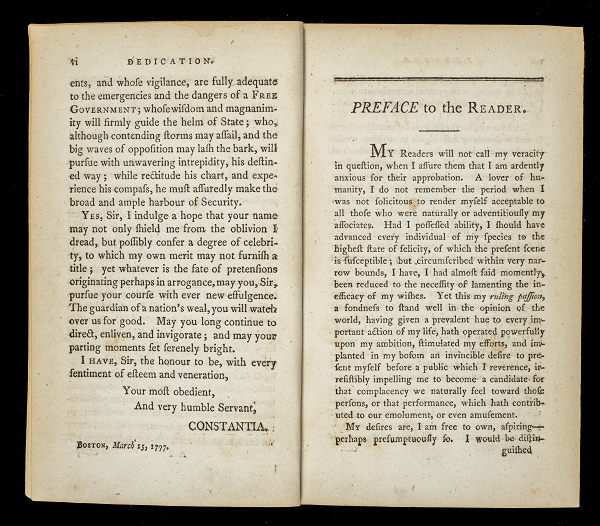

Judith Sargent Murray, “No. 87,” The Gleaner, A Miscellaneous Production in Three Volumes, Vol. 1 (Boston: J Thomas and E.T. Andrews, 1798). New-York Historical Society Library.

Background

In 1787, representatives from each state gathered in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. They soon decided that the articles were too flawed to serve as the basis of the U.S. government. A whole new governing document was needed. During the process of drafting and ratifying the U.S. Constitution, two political parties emerged.

One party was called Federalist. Federalists believed that having a strong central government was key to making the United States a success. For Federalists, class distinctions mattered. They thought it was better for the country if the wealthiest and most educated people were in charge. Federalists supported ratifying the new U.S. Constitution. John Adams and Alexander Hamilton were famous Federalists.

The second party was called Anti-Federalist. Anti-Federalists worried that a strong central government would threaten the freedom of individuals. Anti-Federalists opposed the new U.S. Constitution because it did not have enough protections for individual citizens. Thomas Jefferson and Samuel Adams were famous Anti-Federalists.

Federalists won the ratification debate when the new Constitution became the official governing document in the United States in 1788. But their victory was not complete. Anti-Federalists rallied to ratify the Bill of Rights in 1791. Those 10 amendments to the Constitution protected individual liberties. Federalists and Anti-Federalists continued to fight over the future of the U.S. government throughout the Federal period.

Many women took sides in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist debates. Women who took an interest in politics were nicknamed “politicians.” Women politicians wore accessories supporting their political parties and enthusiastically debated with friends and family. But they had to be careful. If a woman was too outspoken about her beliefs, she was accused of forgetting her place in the social hierarchy.

About the Document

Mercy Otis Warren and Judith Sargent Murray were two of the most published women writers of the Federal period. They both supported the American Revolution, but they had different ideas about how the new government should work. They both used their writing to rally support for their causes.

Mercy Otis Warren’s essay “Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State Conventions” was Anti-Federalist. She first published the piece under the name of Elbridge Gerry, who was a well-known opponent of a strong central government. By using his name, Mercy made certain readers took her essay seriously. In this excerpt, Mercy argues that the new Constitution is dangerous because it does not guarantee individual liberties. This popular Anti-Federalist claim led to the ratification of the Bill of Rights.

Judith Sargent Murray’s essay No. 87 from her series The Gleaner demonstrates how Federalist and Anti-Federalist partisanship continued long after the ratification of the Constitution. In this excerpt, she argues that too much personal liberty is dangerous for the country. She thought it would be best if every person stayed within their social class and respected the hierarchy. This was a common concern among Federalists, who worried that the Anti-Federalist emphasis on personal liberty would result in mob rule.

Vocabulary

- Anti-Federalist: Person who is opposed to having a strong central government.

- Articles of Confederation: The original governing document of the United States.

- Bill of Rights: The first ten amendments to the Constitution. The Bill of Rights protects the liberties of individual U.S. citizens.

- Constitution: The governing document of the United States.

- dedication: The part of a book where the author honors or thanks someone who inspired or supported them.

- Federal period: The early years of the United States, usually defined as 1790–1830.

- Federalist: Person who wanted a strong central government.

- partisanship: Dedication to a party or belief.

- political spectrum: Range of political beliefs.

- ratify: Formally accept. In the U.S. government, the Constitution and amendments are ratified when three-fourths of the states vote to accept them.

Discussion Questions

- Why does Mercy Otis Warren oppose ratification of the U.S. Constitution?

- Why does Judith Sargent Murray believe John Adams is an exemplary president and politician?

- What do these excerpts reveal about women’s political engagement in the Federal period?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.8: The Constitutional Convention and Debates Over Ratification

- AP Government Connections:

- 1.5: Ratification of the U.S. Constitution

- 3.1: The Bill of Rights

- 3.2: First Amendment: Freedom of religion

- 3.3: First Amendment: Freedom of speech

- 3.4: First Amendment: Freedom of the press

- 3.5: Second Amendment: Right to bear arms

- Write a dialogue between Mercy Otis Warren and Judith Sargent Murray. What do you think these two women would have to say to each other on the question of U.S. government?

- Mercy Otis Warren’s entire essay against the Constitution is available here. Compare and contrast her arguments with those put forth by Hamilton, Adams, and Jay in the Federalist papers.

- Analyze Warren’s essay together with the excerpt from her Revolutionary-era play the Adulateur. What do these two pieces reveal about Warren’s politics over the course of her life?

- Teach Judith Sargent Murray’s dedication together with the excerpt from her famous essay “On the Equality of the Sexes”. How do you think Murray reconciled her Federalist politics with her belief that women should be given more opportunities in society?

- To further explore women’s political engagement in the Federal period, see any of the following: New Jersey’s Suffrage Experiment, Republican Motherhood, Benevolent Societies, Fashion and Politics, Life Story: Dolley Madison, and Life Story: Margaret Bayard Smith.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP; POWER AND POLITICS