Agathe Saint-Père was born into a high-ranking French colonist family in Montréal on February 25, 1657. Her father Jean first arrived from France in 1643 to support the mission of converting Indigenous people to Catholicism. He settled in Ville-Marie, which eventually grew into the city of Montréal. He was the first clerk of the court and the first notary in the settlement. Agathe’s mother, Mathurine Gode, was also born in France. She moved to New France with her parents and three siblings as a child. Jean and Mathurine married in Montréal on September 25, 1651. Agathe was their only child who survived to adulthood.

Agathe’s father and grandfather were killed by Haudenosaunee warriors when she was only eight months old. Mathurine married a wealthy merchant named Jacques Lemoyne several months later. Historical records suggest that Mathurine had at least five sons and five daughters with her second husband, making Agathe the eldest of at least eleven children. She was expected to help her mother care for her younger siblings. Agathe also attended school, where she was taught reading, writing, and needlework.

When Mathurine died during childbirth in December 1672, Agathe took over her duties. At only fifteen years old, she was responsible for raising ten children and managing the family’s household and servants. Most women of her social class in New France married as teenagers or in their early twenties, but it appears that Agathe delayed her own marriage to take care of her family. She ran the Lemoyne household for thirteen years before she married Pierre Legardeur de Repentigny on November 28, 1685. She was twenty-eight years old.

Agathe and Pierre had seven children between 1686 and 1698. In addition to her duties as head of the household, Agathe proved to be a talented businesswoman during this time. Pierre owned several businesses, but according to records it was Agathe who traded land and fur-trading licenses. She also lent money to other colonists.

“Agathe seized the opportunity to grow her textile experimentation into a larger business.”

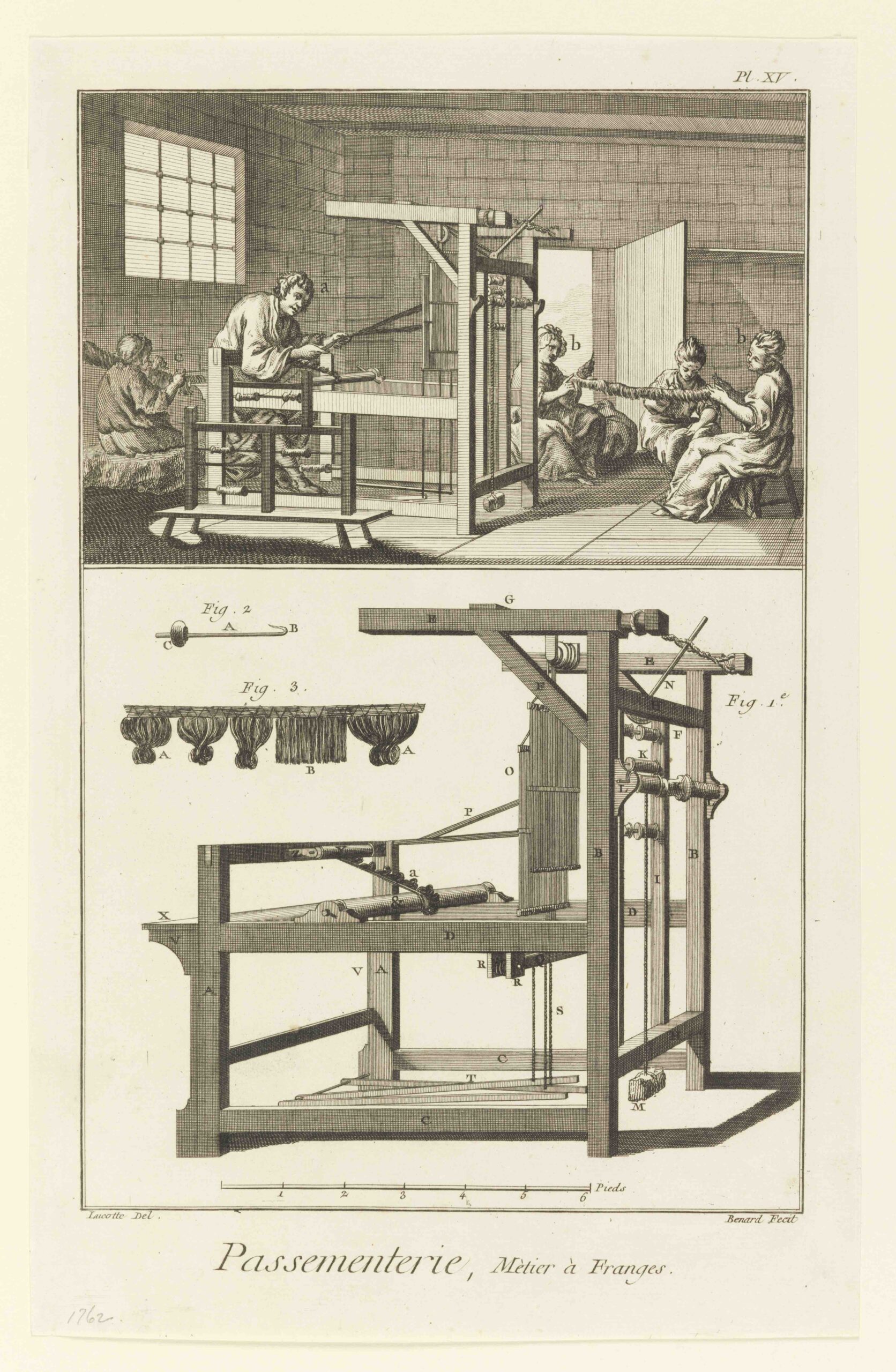

Agathe soon developed a new area of interest. At the time, most textiles in New France were imported from France. Fewer than ten ships a year arrived from France, making any materials that had to be shipped across the Atlantic incredibly rare and expensive. Agathe began to experiment with weaving textiles locally. She developed her own fabrics using resources from the local environment, like buffalo hair and cottonweed. She sent samples of her fabrics to King Louis XIV, who was impressed with her textiles.

In 1705 a shipwreck interrupted the import of goods from France. Agathe seized the opportunity to grow her textile experimentation into a larger business. There was only one weaving loom in Montréal, so Agathe had a second built to increase production. But she needed staff for her business to grow, and there were not enough skilled weavers in New France.

Agathe heard that the nearby Abenaki community had several captive English colonists, and that some were skilled weavers. She paid the Abenaki a ransom and brought nine of the English colonists to work in her textile mill. Most of the captive weavers were men, although there was at least one married couple.

Agathe did not pay her captive weavers, who did not have a specified legal status under the law in New France. They lived in her home and probably performed domestic labor in addition to their weaving work. Their skill soon made her business a success. Agathe recruited several French colonists as apprentice weavers. The captives taught the apprentices how to weave.

Agathe’s workshop produced a strong coarse cloth used for the undershirts of lower-class residents of New France. This underlayer was very important to the success of the colony because it helped laborers stay warm in the harsh winters. By producing this cloth, Agatha helped the colony survive the shortage caused by the shipwreck. Two high-level officials of New France wrote to France to ask the king to support Agathe’s business. They stated that her weaving workshop produced much-needed textiles and blankets for the community of New France. She was granted an annual financial reward from the king in recognition for her contributions to the colony.

Soon, Agathe’s workshop produced the majority of the textiles sold in the colony. In 1706 the second highest-ranking official of New France wrote that without her textile mill, half of the “poor people in that poor country … would be without shirts.” Agathe had twenty-eight employees in her workshop by this time, and her business was still growing. The following year, she reported that seventy people were employed by her business.

In 1707 representatives from Boston came to recover the captive English weavers. They repaid Agathe the ransom she had paid the Abenaki. At that point, Agathe’s apprentice program was such a success that French weavers could continue to operate her textile mill without any noticeable change in the quality or speed of production.

Agathe sold her textile business in 1713. For the next two decades she expanded her family’s wealth by buying and selling land. When Pierre died in 1736, Agathe moved into the general hospital of Quebec. It was common in the 1700s for French women of Agathe’s social status to live in hospitals in old age. Agathe’s daughter was the mother superior of the Quebec hospital, so she spent the rest of her days in comfort.

While the exact date has not been confirmed, Agathe most likely died around 1748. Today, she is considered the founder of the Canadian textile industry.

Vocabulary

- Abenaki: An Indigenous community that originally inhabited the area now known as northern New England and Quebec, Canada. Today the Abenaki live in Vermont, Maine, and Quebec, Canada.

- Catholicism: A Christian religion that is led by the pope in Rome.

- Haudenosaunee: The preferred name of the tribal alliance previously known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Haudenosaunee territory covers much of upstate and western New York. There were five tribes in the original Haudenosaunee alliance: Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca. The Tuscarora joined the alliance in 1722.

- mother superior: The head of a community of nuns.

- ransom: A payment made to free a person who has been kidnapped.

-

Discussion Questions

- How was Agathe de Saint-Père able to start a business? What opportunities was she able to take advantage of to make her business a success?

- Why did Agathe de Saint-Père need weavers to work in her shop? What does her solution to this problem reveal about life in the North American colonies in the 1700s?

- Why was Agathe de Saint-Père’s business considered a service to New France? Why did the king of France support her business endeavors?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 2.5 Interactions Between American Indians and Europeans

- Include this life story in a lesson about business and industry in the colonies. This life story shows how colonists had to establish new businesses to support their community, and adapted to local resources.

- Analyze a 1705 letter Agathe de Saint-Père wrote about her business through the Canadian Museum of History here.

- Pair this life story with Life Story: Charlotte-Françoise Juchereau de Denis, another woman who was able to establish a successful business in New France.

- Combine this life story with Life Story: Esther Wheelwright to learn more about the exchange of captives between the English, French, and Haudenosaunee.

- For a larger lesson on women as business owners in the American colonies, teach this resource alongside any of the following:

Themes

WORK, LABOR, AND ECONOMY; IMMIGRATION, MIGRATION, AND SETTLEMENT