This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Tituba was an enslaved Native American woman who lived in Salem Village, Massachusetts, in the late 1600s. Historical records do not contain any information about her early life, or how she came to be enslaved. In 1692 Tituba lived and worked in the home of Reverend Samuel Parris, the minister of Salem Village. She helped Samuel’s wife and daughters do all the work necessary to keep their home running.

In January 1692 Samuel’s daughter Betty and his niece Abigail Williams became mysteriously ill. A doctor, brought in to examine the girls, worried that someone was performing witchcraft to punish the minister and his family. A concerned church member told Tituba to make a witch cake to reveal the identity of the person who was tormenting the girls. Tituba followed the church member’s instructions. She mixed the girls’ urine with rye meal to make a small cake, and then fed it to the family dog. When she was finished, the girls accused Tituba of witchcraft.

Tituba was interrogated by Samuel and his most trusted advisors. She denied being a witch, and swore that she had done nothing to hurt the girls. Betty and Abigail were too young to be witnesses in a legal case. Samuel may have also have suspected that they were lying. Tituba was not arrested, but Samuel punished her anyway. Many years later, Tituba revealed that Samuel beat her for weeks until she confessed to witchcraft. These confessions would have dire consequences for the entire community of Salem.

On February 25 two more young women made witchcraft accusations. Ann Putnam, the daughter of church members, and Betty Hubbard, a seventeen-year-old indentured servant, said Tituba was using magic to hurt them with the help of two other women: Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne. Betty Hubbard was old enough to be a witness in the courts, and her testimony inspired the community to take formal legal action. All three accused women were arrested on February 29.

On March 1 the three women were questioned by magistrates in the Salem meeting house. Their fellow community members, including their accusers, watched. As accused witches, they were kept in chains, and the audience was allowed to speak up at any time to share their suspicions about the women. Throughout the questioning, the four accusers screamed accusations.

Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne refused to confess to practicing witchcraft, although Sarah Good did say she thought Sarah Osborne might be a witch. But everything changed when the magistrates started questioning Tituba. She told them that the devil had come to her and asked her to join him. Tituba said she had seen Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good use magic to hurt the girls. She revealed that they had been helped by two other women and a man from Boston whom Tituba did not recognize. She told them that Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne had demons in the form of animal companions who helped them commit their crimes. She ended by confessing that they had bullied her into becoming a witch and hurting the girls.

While Tituba spoke, her accusers stopped screaming. The magistrates believed this was evidence that Tituba was telling the truth. When she finished, the girls started screaming again, and Tituba told the magistrates that she could see the spirit of Sarah Good hurting them. Then, Tituba herself claimed to be struck blind and mute. Tituba’s accusers said they could see Sarah Good hurting her for confessing. The interrogation ended in chaos.

The next day the magistrates interviewed Tituba in her jail cell, where she gave them even more details. She told the magistrates that she had signed the devil’s book with blood, and that the devil had shown her Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne’s signatures. She revealed that the book had nine signatures total, implying there were more witches within the community. She explained that she had flown on sticks with her fellow witches. Finally, she confessed that the witches had held a meeting in her master’s home and used their power to keep him from finding out.

Many years later, Tituba revealed that Samuel beat her for weeks until she confessed to being a witch.

Tituba’s testimony convinced her community that there was a large conspiracy of witches in Salem, and the magistrates believed her because her story remained consistent no matter how many times they interrogated her. They did not know that Samuel had beaten Tituba until she created this story to save herself.

After Tituba’s confession, more and more people reported seeing witches and spirits. Their stories lined up perfectly with Tituba’s, probably because they had all heard her confession in the meeting house. Instead of wondering whether people were imagining things, the magistrates accepted this as proof that everything Tituba said was true.

As a confessed witch, Tituba was no longer considered an immediate threat to the community. In fact, no person who confessed to practicing witchcraft was executed during the Salem Witch Trials. On May 12 Tituba was sent to a prison in Boston to make room for all the new suspects who were being arrested in Salem Village. In total, 144 people were accused of practicing witchcraft. Fifty-four confessed, and their testimony was used in the trials of other suspects. Tituba was regularly brought back to Salem to testify at the trials of a number of people who were convicted and executed for witchcraft, but it is difficult to know for sure, because the official trial records were lost. Twenty people were convicted of witchcraft and executed. Three more died in prison before they could be tried.

Tituba spent an entire year in jail because no one would pay her bail. But her usefulness as a witness allowed her to outlive the hysteria. By the time she was brought to trial on May 9, 1693, people were questioning whether any of the witchcraft accusations had been real. The word “ignoramus” was written on the back of her charges, meaning the court found no truth in the charges and recommended the case be dismissed.

Tituba was no longer accused of any crime, but Samuel Parris refused to pay the fees necessary to free Tituba from prison. She was sold to another English settler who agreed to cover them. Historians know nothing else about her life.

Since 1693 historians, writers, playwrights, and filmmakers have told and retold Tituba’s story, embellishing and adjusting it to appeal to their audiences. Today, the myth of Tituba bears little resemblance to the actual woman, who told a story to save her life.

Vocabulary

- bail: When a person gives money to the court as a guarantee that they will return for their trial, and then is allowed to leave prison.

- familiar: A demon who obeys a witch, and often assumes the form of an animal.

- ignoramus: An ignorant or stupid person.

- magistrate: A member of the court who can oversee hearings and take testimony.

- meal: Coarsely ground grains.

- minister: A person who can lead Christian religious services and a congregation.

- Salem Village: The small satellite community of Salem where the witchcraft accusations of 1692 started. Today, this community is called Danvers, Massachusetts.

- subhuman: Less than human.

Discussion Questions

- What circumstances made Tituba a vulnerable person in Salem Village?

- Why did Tituba confess to being a witch? What were the consequences of her confession?

- How did Tituba survive the Salem Witch Trials? What do her experiences reveal about this event?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 2.5 Interactions Between American Indians and Europeans

- Include this life story in a lesson about the Salem Witch Trials.

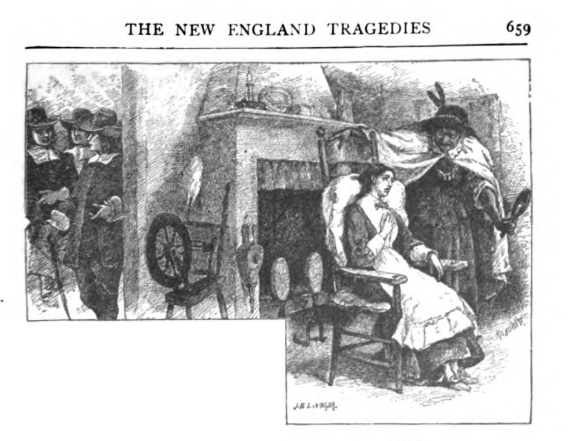

- Compare this life story of Tituba with the image accompanying it, which was produced as an illustration for an 1800s retelling of the Salem Witch Trials. How does the illustration change the story? Why would the author and illustrator choose to depict her in this way?

- Ask students to compare and contrast this life story with modern-day versions of the Tituba story. What changes have been made over time? Why is it important to know the original facts of the story?

- Pair this resource with Connecticut Witch Trials. Compare and contrast how the three women were treated by their communities in the English colonies and why they received different treatment.

- Combine this life story with Life Story: Weetamoo and Life Story: Esther Wheelwright to give your students background information about the wars between English Settlers and Indigenous people.

- For a larger lesson on witchcraft in this period, combine this life story with the following:

- For a larger lesson on the strict religious rules that governed the lives of women in the New England colonies, combine this life story with the following:

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS; AMERICAN CULTURE