Nancy Morgan Hart was born around the year 1735, the daughter of Thomas and Rebecca Morgan. She grew up in the Yadkin River Valley, which was along the western frontier of the North Carolina colony. Living on the colonial frontier, every member of the Morgan household was required to work hard to keep the family fed, clothed, and safe. Nancy would have learned traditional women’s work like housekeeping and child-rearing as well as the traditionally masculine skills of hunting, farming, fishing, and repair work.

Nancy married Benjamin Hart around the year 1760. Benjamin was also a farmer, and he and Nancy joined the growing number of settlers who moved around the colonial frontier in search of better land and opportunity. This was a very difficult life. Every move required the couple to start over, and the lands they were moving into were already inhabited by Native people who resisted their arrival. Nancy and Benjamin settled for a while in South Carolina, and by the time of the American Revolution, they were living along the Broad River in the colony of Georgia. During this time, Nancy gave birth to eight children: two girls and six boys.

Benjamin fought with the Georgia militia for the Patriots during the American Revolution. This meant that Nancy was solely responsible for keeping her family and their farm running. She must have struggled, because in 1781, the Georgia Executive Council voted to give the Hart family twenty bushels of corn to help them survive. After the war, Nancy and Benjamin moved again, this time to the Georgia coast, settling in the town Brunswick. While in Brunswick the family finally achieved prosperity. According to tax records, in 1794 Benjamin owned fifty acres of land and fifteen enslaved people. He became an important member of the local courts. Nancy was now a prosperous housewife. But the allure of the frontier still appealed to the family.

In 1801, Benjamin advertised in the local paper that he was selling his land so he could move, but he passed away before the sale could be completed. Nancy, now a widow, moved to Clarks County, Georgia, to live with her son John. Eventually, she moved with John and his family to Henderson, Kentucky. Historians don’t know exactly when she died. When John died in 1821, Nancy was not mentioned in his will, so it is possible that she had passed away before him. Local legends say that she lived until 1830. Either way, she left no will, which indicates that when she died she had no property of her own.

These are the known facts of Nancy Morgan Hart’s life, painstakingly pieced together from the local historical records of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Kentucky. From these records, it seems clear that she was a woman who lived a challenging life, but nothing too different from the experience of the thousands of other women who lived along the western frontier in the eighteenth century. So why is she remembered as one of the heroes of the American Revolution?

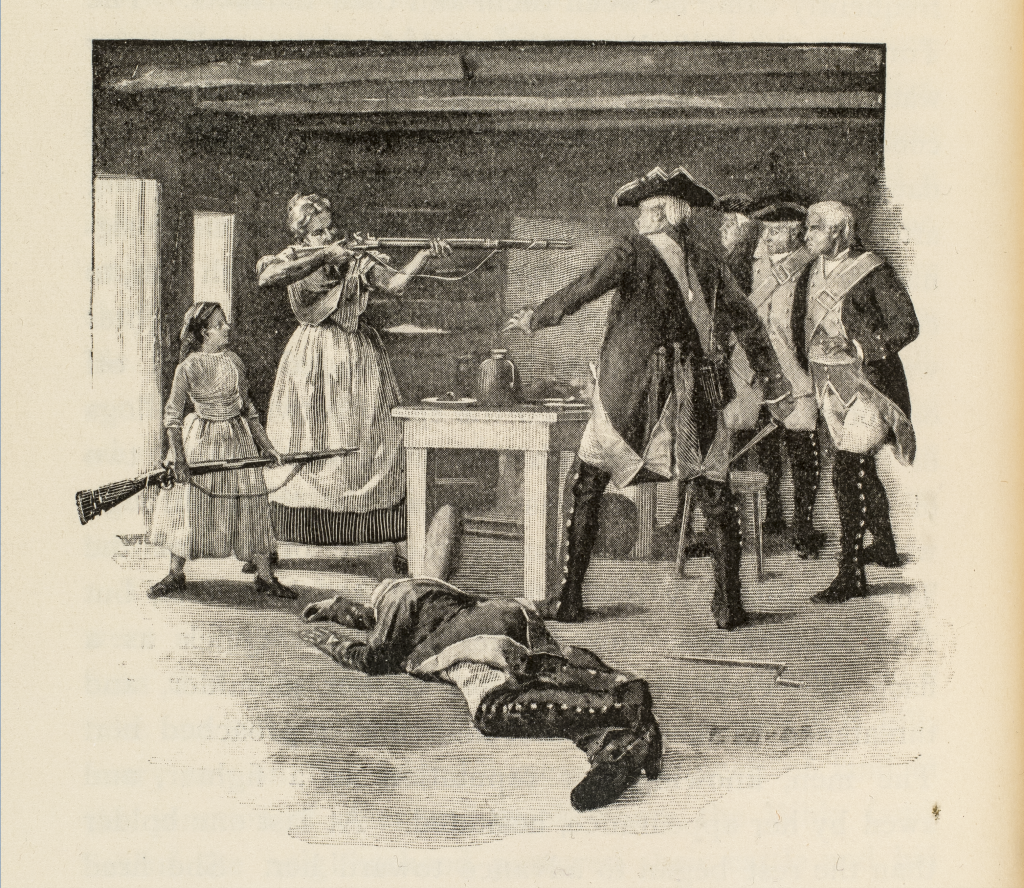

The myth of Nancy Morgan Hart first appeared in print in 1825. The Southern Recorder, the local newspaper of Milledgeville, Georgia, published a short story recounting Nancy’s heroics during the Revolutionary War. According to the Southern Recorder, Nancy was a passionate Patriot. One day a group of Loyalist soldiers came to her home and demanded a meal. Nancy welcomed them inside, set the table with food and drink, and once the soldiers relaxed she took one of their muskets and held them hostage until her children could bring some neighboring Patriots to help her. The Loyalists were afraid to fight back, because Nancy was cross-eyed, and they could never tell exactly who she was aiming the musket at. When her neighbors arrived, they executed all of the Loyalists.

This story is amazing, but there is just one problem: There is no historical evidence to support it! Nancy’s actions were never mentioned in local government records, and in her lifetime, she was never recognized by the local or federal government for her bravery. Historians think the story might have been a fiction invented for the local newspaper.

The problem is, once the story was out there, it started to spread and grow. The next time Nancy’s story appeared in print was in 1848, in the book The Women of the American Revolution by Elizabeth Fries Ellet. Elizabeth said she heard the story from a gentleman in Georgia. Her printed version has a lot more details. In this story, the Loyalist soldiers visited Nancy because they’d heard she helped a Patriot spy escape by letting him ride his horse straight through her home. Nancy proudly admitted that when the authorities chasing the spy came to her home, she kept the door locked and pretended to be sick, tricking them into giving up the chase. Furious at her betrayal, the Loyalist soldiers demanded she cook them a meal, and when she told them all her food had already been stolen, they shot her only remaining turkey and demanded she roast it. Again, Nancy lured them into a false sense of security, but this time she and her daughter were trying to sneak their muskets out of the house when the Loyalists caught them. The Loyalists attacked, and Nancy shot two before the rest gave up the fight and agreed to wait quietly. When her neighbors arrived, Nancy said that shooting the prisoners would be too kind. She insisted that they be hanged. In this version, Nancy is much more blood thirsty than when her story was first told.

Every person who learned and then shared Nancy’s story was inspired by the idea that even the most common colonists were moved to heroic feats by their passion for the cause.

From The Women of the American Revolution, Nancy’s fame continued to spread, and over time new stories were added to her myth. In these new stories, Nancy became a Patriot spy who braved the Georgia swamps to bring critical information to American troops. She infiltrated a British Army encampment and learned secret battle plans. She burned a Loyalist spy with a pot of boiling soap. She grew to over six feet tall, with a mane of red hair and small pox scars that telegraphed her tough-as-nails personality. She came to be described as a sharpshooter, skilled hunter, and expert farmwife who could bake bread on the back of a hoe. Georgia named a county after her, and there are monuments to her in Georgia and Kentucky.

What is most interesting about Nancy is not this growing collection of stories and details, but what her myth means to the people who share and retell it, and what it reveals about the ways Americans want to remember the American Revolution. Every person who learned and then shared her story was inspired by the idea that even the most common colonists were moved to heroic feats by their passion for the cause. And every writer has added a new piece to her story to reflect the values of his or her time.

Nancy is not the only Revolution-era person to become more myth than fact. Betsy Ross is another real person whose beloved myth first appeared fifty years after the end of the war, and even George Washington himself is dogged by the myth of the cherry tree. That doesn’t mean we should stop learning these stories, we just need to shift our focus to understanding why these stories are told, and what they reveal about the values of American history.

Vocabulary

- bushel: A dry goods measurement equal to 64 pints.

- hanged: to hang by the neck until dead.

- hoe: A tool with a thin, flat blade used in farming.

- Loyalist: A person who supported the British during the American Revolution.

- Patriot: A person who supported the American rebellion during the American Revolution.

- will: A legal declaration of how a person wants their property distributed after their death.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think Nancy’s story is still being shared today?

- Why do you think Nancy’s story changes with every retelling?

- What is the historical value of studying American myths and legends?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.5: American Revolution

- Use Nancy’s life story to introduce your students to the idea of American Revolution mythology.

- Each new layer added to Nancy’s story adds levels of meaning and symbolism. Ask students to consider the details in her myth, and why people would have added them. For example, why does it matter that she cooked her bread on the back of a hoe? Why did the second version of her story add the detail that she insisted on hanging the Loyalists? Why do authors make her cross-eyed? Invite students to read different versions of her story that they find online and add to their list of symbols.

- Even today, a number of seemingly trustworthy sources relate Nancy Morgan Hart’s story as fact, with a variety of works cited. This provides an excellent opportunity for your students to learn how to critique online sources and trace bibliographies.

- Compare the legends surrounding Nancy Morgan Hart with the actual lived experiences of any of the following women. Why did her myth grow more popular than these real lived experiences: Spinning Wheels, Spinning Bees, A Call to Arms, The Edenton Tea Party, Sentiments of an American Woman, Life Story: Margaret Corbin, and Life Story: Lorenda Holmes.

- Have students consider how women of the colonial period and the Revolutionary era have been remembered through art and storytelling by creating their own portraits of Nancy Morgan Hart in this arts integration activity.

Themes

DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY; AMERICAN CULTURE

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For resources relating to the American Revolution in New York, see The Battle of Brooklyn.