Document Text |

Summary |

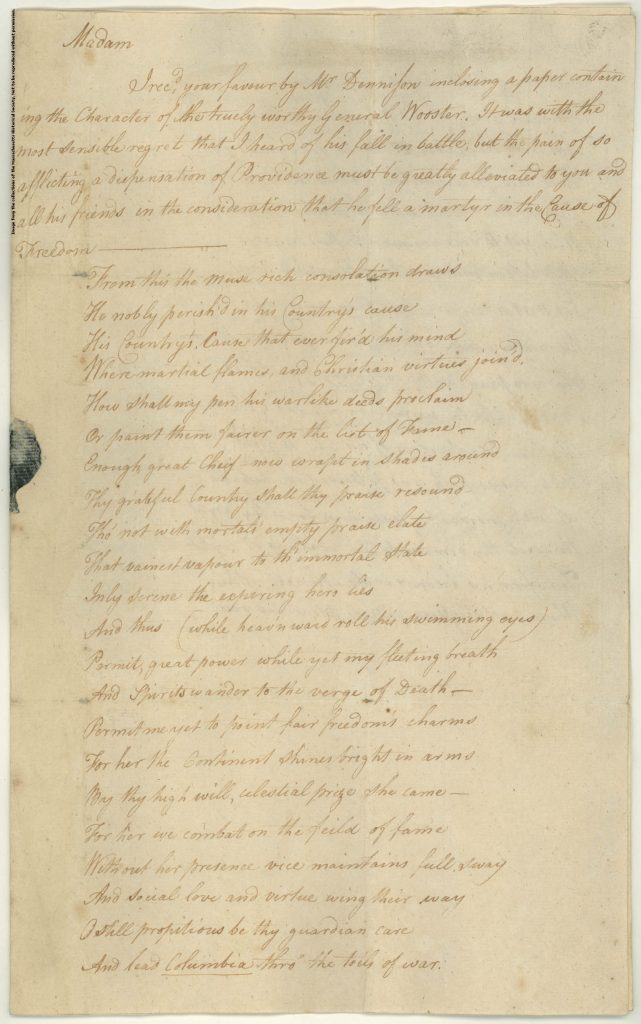

| Madam I received your favor by Mr. Dennison inclosing a paper containing the character of the truly worthy General Wooster. It was with the most sensible regret that I heard of his fall in battle, but the pain of so afflicting a dispensation of Providence must be greatly alleviated to you and all his friends in the consideration that he fell a martyr in the Cause of Freedom – |

I received your letter with the article about General Wooster’s death from Mr. Dennison. I was so sorry to hear he was killed in battle. The sadness you feel at this act of God must be lessened by the knowledge that he died fighting for freedom. |

| From this the muse rich consolation draws He nobly perished in his Country’s cause His Country’s cause that ever fired his mind Where martial flames, and Christian virtues joined. How shall my pen his warlike deeds proclaim Or paint them fairer on the list of Fame — Enough, great Chief — now wrapped in shades around Thy grateful Country shall thy praise resound — Though not with mortals’ empty praise elate That vainest vapor to the immortal State Inly serene the expiring hero lies And thus (while heavenward roll his swimming eyes): |

|

| “Permit, great power while yet my fleeting breath And Spirits wander to the verge of Death — Permit me yet to point fair freedom’s charms For her the Continent shines bright in arms By thy high will, celestial prize she came — For her we combat on the field of fame Without her presence vice maintains full sway And social love and virtue wing their way O still propitious be thy guardian care And lead Columbia through the toils of war. With thine own hand conduct them and defend And bring the dreadful contest to an end — Forever grateful let them live to thee And keep them ever Virtuous, brave, and free — But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find Divine acceptance with the Almighty mind — While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace And hold in bondage Africa’s blameless race; Let virtue reign — And those accord our prayers Be victory ours, and generous freedom theirs.” |

|

| The hero prayed — the wandering spirit fled And sought the unknown regions of the dead — Tis thine fair partner of his life, to find His virtuous path and follow close behind — A little moment steals him from thy sight He waits thy coming to the realms of light Freed from his labors in the ethereal skies Where in succession endless pleasures rise! — |

|

| You will do me a great favor by returning to me by the first opportunity those books that remain unsold and remitting the money for those that are sold — I can easily dispose of them here for 12Lmo each – | Please send me any books you haven’t sold and the money you’ve collected for those you did sell. I can sell them here for a good price. |

| I am greatly obliged to you for the care you show me, and your condescension in taking so much pains for my Interest — I am extremely sorry not to have been honored with a personal acquaintance with you — if the foregoing lines meet with your acceptance and approbation I shall think them highly honored. | I really appreciate all the support you’ve given me. I’m sorry we’ve never met in person. If you like my poem, I will be honored. |

| I hope you will pardon the length of my letter, when the reason is apparent — fondness of the subject and — the highest respect for the deceased — I sincerely sympathize with you in the great loss you and your family sustain and am sincerely

Your friend and very humble servant |

I hope you’ll forgive how long this letter is when you realize it is inspired by my respect for your husband. I send you and your family my sympathy. |

“Phillis Wheatley to Mary Wooster,” July 15, 1778. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Background

Phillis Wheatley was born around the year 1753 in West Africa. When she was seven or eight years old, she was forced to endure the Middle Passage, and when she arrived in Boston, she was sold to John and Susanna Wheatley. They named her Phillis after the ship that brought her from Africa.

Phillis was a brilliant child, and her owners encouraged her to learn to read and write. Phillis proved to be a very talented poet. John and Susanna were proud of her work, and they began publishing it in newspapers in 1767. These early works made her the first African woman published in the colonies. But even as Phillis’s fame grew, she was still enslaved. Her owners and readers loved her work, but they still viewed her as property.

By 1772, Phillis had enough poems to make a book, but she could not find an American publisher for it. So, the Wheatleys sent Phillis to London with their son to find a publisher, and in 1773, her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, made its debut. It was widely praised.

Publishing a book was not the only thing Phillis accomplished in London. In England, there was a law that no slaveowner who brought an enslaved person to England could force them to return to the colonies. Phillis used this law to negotiate with the Wheatleys and gain her freedom.

Phillis Wheatley lived the rest of her life in Boston, where she continued to write poetry. Her works are unique in the way they blend support for the American Revolution with admonishments against the practice of slavery. She died suddenly in 1784, before she was able to publish a second book of poetry.

About the Document

In this letter, we get to see the many sides of Phillis Wheatley. Phillis the friend is reaching out to the wife of a friend after hearing about his death in battle. Phillis the poet sends a beautiful poem in his honor. Phillis the Patriot praises the justness of the American cause. But Phillis the abolitionist points out the hypocrisy of the colonists fighting for independence while they continue to enslave and oppress people of African descent. And Phillis the businesswoman, who must make enough money to support herself and her family, asks for the return of any unsold copies of her book (which General Wooster had agreed to sell on her behalf) so she can sell them herself.

Vocabulary

- abolitionist: A person who wanted to end the practice of slavery.

- accord: Unify.

- Africa’s blameless race: Innocent Black people.

- bondage: Slavery.

- celestial: Heavenly.

- Christian virtues: Morals based on the teachings of Jesus Christ.

- Columbia: America.

- combat: Fighting.

- consolation: Comfort.

- deed: Action.

- divine: Heavenly.

- elate: Fill with joy or pride.

- ethereal: Heavenly.

- expiring: Dying.

- fleeting: Passing.

- Inly serene: Peacefully.

- martial: Warlike.

- Middle Passage: The part of the Triangle Trade that brought enslaved people from Africa to the New World.

- mortals: Humans.

- muse: Goddess of poetry.

- perished: Died.

- presumptuous: Arrogant.

- propitious: Encouraging.

- resound: Echo loudly.

- shades: Shadows.

- sway: Control.

- swimming: Watering.

- thine: Your.

- thee: You.

- vainest vapor: Foolish idea.

- vice: Moral failing.

- virtue: Moral excellence.

Discussion Questions

- How does Phillis Wheatley characterize the American Revolution? How does she characterize General Wooster and his wife?

- What problems does Phillis Wheatley raise in regard to the American Revolution?

- What does this poem reveal about the attitudes of enslaved and free Blacks during the American Revolution?

- Why are works of literature, like this poem, valuable sources of historical information?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.6: Influence of Revolutionary Ideals

- Teach this poem in any lesson about the beliefs and experiences of free and enslaved Black people during the American Revolution.

- Phillis Wheatley and Mercy Otis Warren were both women writers of the American Revolution. Compare their works and their life stories for a consideration of how race and class affected their lives and their beliefs.

- Phillis Wheatley wrote this poem to draw attention to the hypocrisy of the Patriots when it came to the practice of slavery. Ask students to follow in her footsteps by writing a poem that addresses a current issue where they feel the U.S. is falling short of its values.

- For a lesson on women’s literature of the American Revolution, teach this poem along with Molly Gutridge’s “A New Touch on the Times” and Mercy Otis Warren’s The Adulateur.

- Teach this document together with any of the following for a lesson on the ways enslaved women exploited the American Revolution to push for manumission and the abolition of slavery: Life Story: Elizabeth Freeman, Life Story: Peggy Gwynn, and Life Story: Deborah Squash.

- Teach this letter along with the document describing the Middle Passage, the Virginia Slave Laws, and the Life Stories of Deborah Squash and Peggy Gwynn, to illuminate for students why Phillis Wheatley felt so passionately about the abolition of slavery.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP; POWER AND POLITICS; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For resources relating to the American Revolution in New York, see The Battle of Brooklyn.

- For more on Phillis Wheatley and the debate over slavery in the Atlantic world, click here to download Revolution! The Atlantic World Reborn.