Artist’s rendering of McLennan’s Female Slave

“Artist’s rendering of McLennan’s Female Slave,” Slavery in New York Curriculum Guide (New York: New-York Historical Society, 2005).

Very few images of Black people were recorded in the colonial era. The drawing that accompanies this life story is an artist’s interpretation of McLennan’s Female Slave based on some of the earliest available photographs of Black people from the mid-19th century. It is intended to help students understand that this woman was a real person not fundamentally different from us.

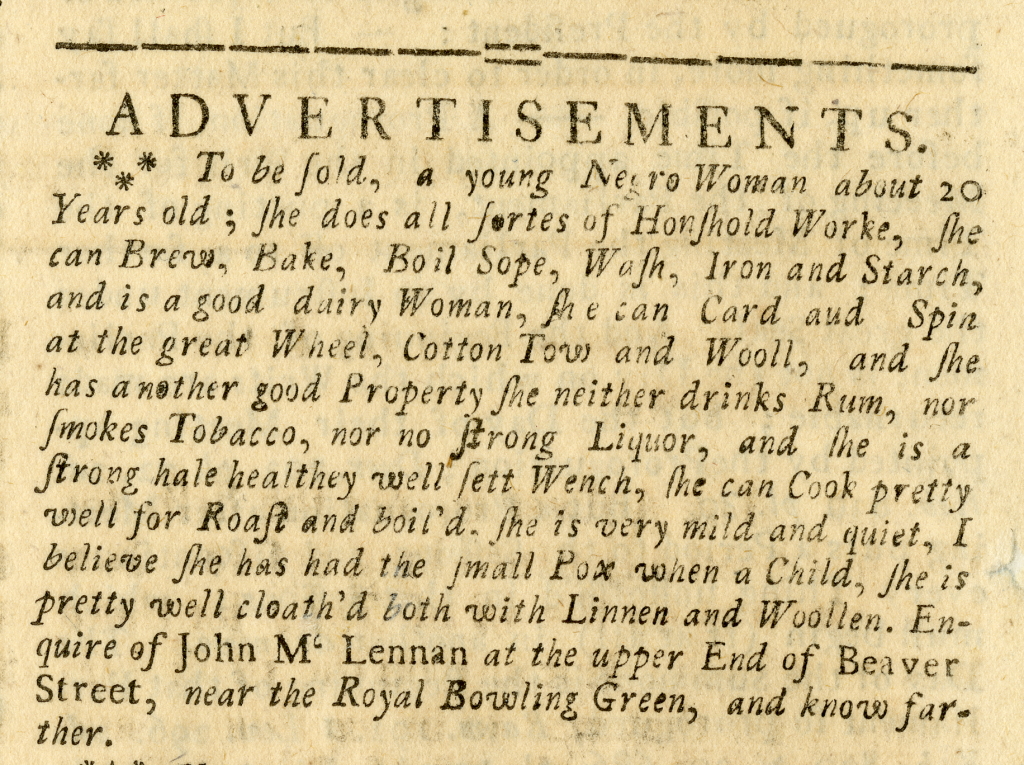

On September 30, 1734, New York City resident John McLennan placed an ad in the New York Weekly Journal newspaper. He was selling “a young negro woman.” McLennan and the enslaved woman lived at the upper end of Beaver Street, near the Royal Bowling Green. He never gives her name, but his ad offers plenty of other information that helps historians better understand what the lives of enslaved women were like in colonial cities.

McLennan guesses that the woman is about 20 years old. It was not unusual for enslaved people to not know their exact ages, because no one kept careful records of their birth. This also indicates that the woman was not born in McLennan’s household, and may have been sold away from her mother when she was young, losing the one person who could give her age with any certainty.

McLennan gives a few other personal qualities of the woman to entice potential buyers. He describes her as “strong, hale, healthy, well-set,” all of which indicate that she was in good health, had a strong, well-fed body, and was therefore capable of doing hard work for long hours. He describes her as mild and quiet, although whether this is her actual personality or just how she acts around her owners is up for debate. He says one of her good qualities is that she does not use tobacco or drink liquor, suggesting that she won’t give potential buyers any trouble in that regard. He also mentions that he thinks she had smallpox once. McLennan includes this detail because it would be attractive to potential buyers. It means she is less likely to die of the disease when there is an epidemic. But it also reveals a lot about the woman’s life experiences. She survived a terrible, deadly disease, and McLennan’s uncertainty about whether this is the case reveals she had smallpox before she lived with him. So, we can presume she’s had at least two, if not more, owners in her twenty years of life. And at this moment she was facing yet another transition.

Aside from these personal details, the ad is full of information about the work the woman is able to do. Many of her skills were related to keeping a colonial family well fed. She can cook roasted or boiled food “pretty well.” This probably means her food was good enough for the daily meals of a working family, but was not fancy enough for the city’s elite. He describes her as a good dairywoman. She can milk cows and churn the milk into butter or use it to make cheese. She can also bake bread and brew beer and ale, tasks that required a lot of manual labor and careful monitoring to make sure the final product was drinkable. These kitchen talents were useful not only in providing for a family’s needs. Any surplus the woman created could be sold to neighbors, putting money in her owner’s pockets.

The woman’s other skills relate to keeping a colonial family clothed. Before industrialization revolutionized the production of fabric and clothing, making and maintaining clothing was a very time-consuming process done by colonial women. McLennan’s assurances that the woman can card and spin both wool and cotton at the “great wheel” make her an incredibly valuable asset for any colonial household. Her thread could be used in the home, or sold for a profit. The woman could also make her own soap, as well as wash, iron, and starch all the family’s clothing and linens. Having an enslaved person who could perform these tasks would make life much easier for any colonial housewife.

Women were bought and sold at the will of their owners, and might pass through many households in the course of their lives.

The final note McLennan includes is that the woman is relatively well-clothed, with both linen and woolen outfits. By indicating that the woman had good clothing for both summer and winter, McLennan was letting any interested buyers know that they did not need to worry about having to spend extra money to dress her.

From these details, we can begin to understand how enslaved women were valued and treated in colonial New York. Enslaved women worked hard at all the time-consuming and difficult tasks that a colonial urban household required to thrive. Women who were healthy and mild-mannered were particularly prized by slave owners, because they could be made to work extra hard without causing problems. They were bought and sold at the will of their owners, and might pass through many households in the course of their lives. They learned a variety of skilled labors that made them particularly valuable to potential owners, who could profit from the goods their enslaved women made. But for all their value, they were still objects. The people who owned them did not even consider it important to acknowledge their names when they were for sale.

Vocabulary

- card: To comb through raw wool or cotton to clean out any dirt, sticks, or other impurities.

- linen: A light, breathable fabric made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Discussion Questions

- What do this woman’s skills and traits reveal about the work she was expected to do in colonial households?

- Everything we know about McLennan’s enslaved woman comes from the ad he placed when he wanted to sell her. Is this a reliable source of information? What important information does this source leave out?

- Why is it important to learn about the day-to-day experiences of enslaved people?

Suggested Activities

- Teach this document in any lesson about slavery in the American colonies.

- The only record of this woman is one that was made to express her value as a commodity. Ask the students to think about how enslaved people might have wanted to be remembered. What details might they have shared about their lives if they were given the opportunity? Use this discussion to remind the students how much we don’t know about the lives of enslaved people, and emphasize the hidden humanity of the people behind these transactional documents.

- Use the image of the spinning wheel to illustrate the work that this woman did for the McLennan household.

- Combine this life story with the runaway advertisement, the Book of Negroes, the slave ship log, and the slave ship manifest for a lesson about the resources historians use to learn about the daily lives of enslaved people in the colonial Americas. What are the drawbacks of these sources? What other ways can historians learn about this historically marginalized group

- Use any of the following resources to help students better understand the many ways enslaved people all over the American colonies fought for their freedom: Fighting for Freedom in New Amsterdam, Life Story: Marie-Josèphe Angélique, Life Story: Dorothy Angola, Life Story: Deborah Squash, Life Story: Peggy Gwynn, Life Story: Elizabeth Freeman, The Book of Negroes, Conditional Manumission, and Runaway Slaves.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For resources relating to the history of the New York colony, see New World—New Netherland—New York.