Document Text |

Summary |

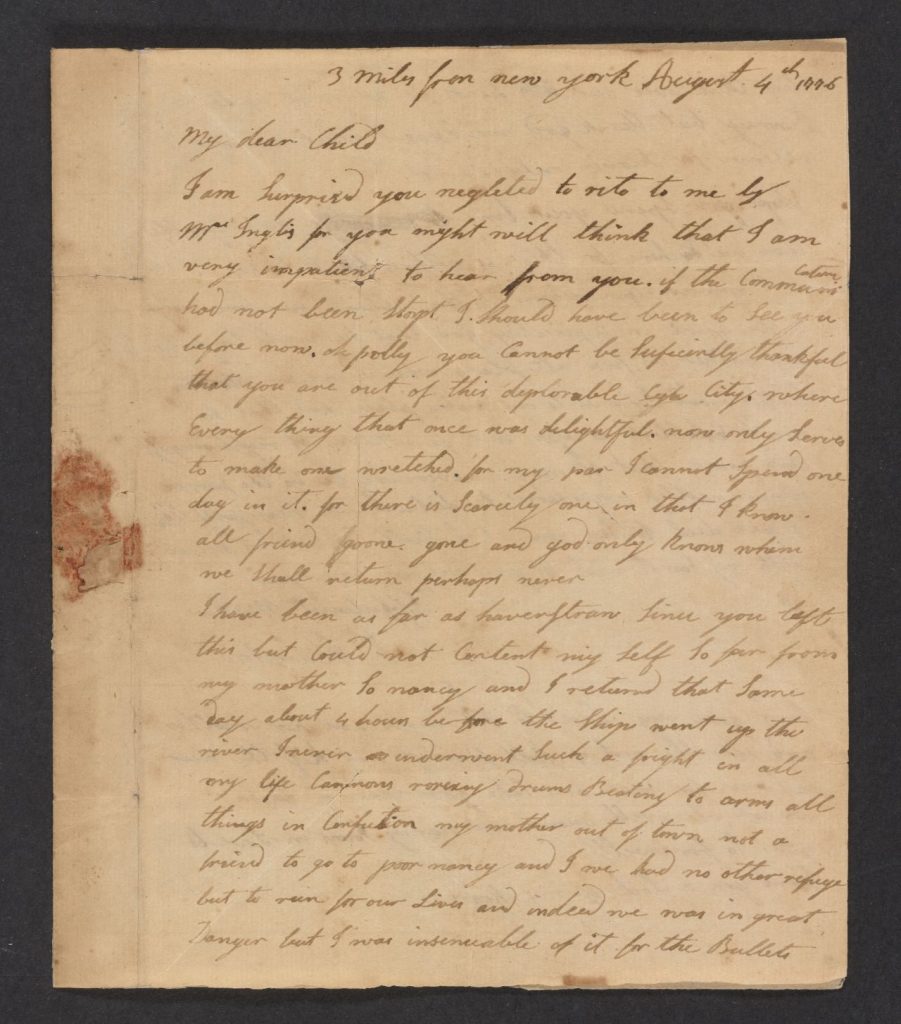

| 3 miles from New York August 4th 1776 |

|

| I have been as far as Haverstraw since you left this but could not content myself so far from my mother so Nancy and I returned that same day about four hours before the ships went up the river. I never underwent such a fright in all my life. Cannons roaring, drums beating to arms all things in confusion, my mother out of town, not a friend to go to. Poor Nancy and I we had no other refuge but to run for our lives and indeed we was in great danger but I was insensible of it for the bullets flew thick over our heads as we went up the Bowery but thank god we escaped. What we are reserved for heaven only knows. | I left the city, but I was worried about my mother, so I came back. That same day, the city was attacked by British ships sailing up the Hudson River. Everything was chaos. I have never been so scared in my life. We ran for our lives while bullets flew over our heads. We escaped, but only heaven knows why. |

| I hope you spend your time more agreeable than we do here for there is nothing to be heard but rumor upon rumor so that I think our time ought to be spent in supplicating god that he would be gracious and gather us from all places whence we are scattered and bring us to our native place and that he would establish us upon such foundations of righteousness and peace that it may nevermore be in the power of our restless adversaries to disturb us. Dear Polly, I have a good deal to say more but shall conclude at present with my earnest wish for your welfare from your

Affectionate Mother |

I hope things are better for you. All we do here is worry about what might happen next. We obsess over rumors, but I think we would do better to ask God to save us. I have more to say, but I’ll stop here. I hope you are well. |

“Mrs. A. Hampton to her daughter, [Three miles from New York],” August 4, 1776. Richard Maass, Collection of Westchester and New York State, courtesy of the Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University Libraries.

Background

Before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, New York City was a thriving port city with a population of around 25,000 people. The early events of the war caused this number to drop quickly. The first mass departure happened when news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord reached New York in April 1775. Excited to join the uprising, the Sons of Liberty rose up and overthrew the colonial government. Lieutenant Governor Cadwallader Colden retreated to Long Island, and Governor Tryon moved his headquarters to a ship in New York Harbor. By September, a third of the city’s population had fled, most of them Loyalists who feared attacks from the Patriots in power. In early 1776, it became clear that New York would be the next major battleground of the war, causing thousands more to flee before the gathering storm. Those who ran left behind homes and possessions that they were unlikely to ever recover. By July 1776, only about 5,000 residents remained. Those who stayed faced grave dangers.

About the Document

In this letter to her daughter, New York resident Mrs. A. Hampton describes a terrifying experience she had on July 12, 1776. George Washington was stationed in New York City with the entire Continental Army. The British Army and Navy were camped on Staten Island, preparing to invade New York. On July 12, British General Howe sent the warships Phoenix and Rose sailing up the Hudson River to test Washington’s defenses. The ships fired on New York, creating a full-blown panic among the general public. Mrs. A. Hampton and others ran through the city, desperate to find a safe place to hide. Washington’s troops were unable to organize an effective response. Reports filed after the incident show that fewer than half the troops reported to their positions, and there were rumors that many of those who did report for duty were drunk. Meanwhile, the captain of the Rose relaxed on the deck of his ship with a bowl of punch and bottle of claret, confident that the American cannons did not have the range to do serious harm to his ship. He was right.

Mrs. A. Hampton’s letter stands as a testament to the very real dangers faced by non-combatants when the war arrived on their doorstep.

Vocabulary

- claret: A red wine.

- Continental Army: The army formed by the Second Continental Congress and led by General George Washington.

- non-combatant: A person who is not engaged in fighting during a war.

- Sons of Liberty: A secret organization of colonists formed to fight all oppression by the British. There were chapters of the Sons of Liberty in every major city of the thirteen colonies.

Discussion Questions

- What was life like in American occupied New York according to Mrs. A. Hampton?

- Why would a person choose to stay in a battleground area?

- Why is it important to read civilian perspectives on the war?

- How were non-combatants affected by the outbreak of the war?

Suggested Activities

- Use this letter in any lesson about life for non-combatants during the American Revolution.

- As this letter demonstrates, having non-combatants present was a huge complication for the commanders of the American Revolution. Invite students to read the August 1776 proclamations of General Washington and General Howe (Resource 6 in The Battle of Brooklyn) to learn how the commanders sought to deal with this problem.

- Teach this letter together with Anne Hulton’s account of the Battles of Lexington and Concord and Lucy Knox’s letters from the home front for a lesson about how non-combatants were affected by the outbreak of the war.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For resources relating to the American Revolution in New York, see The Battle of Brooklyn.