Document Text |

Summary |

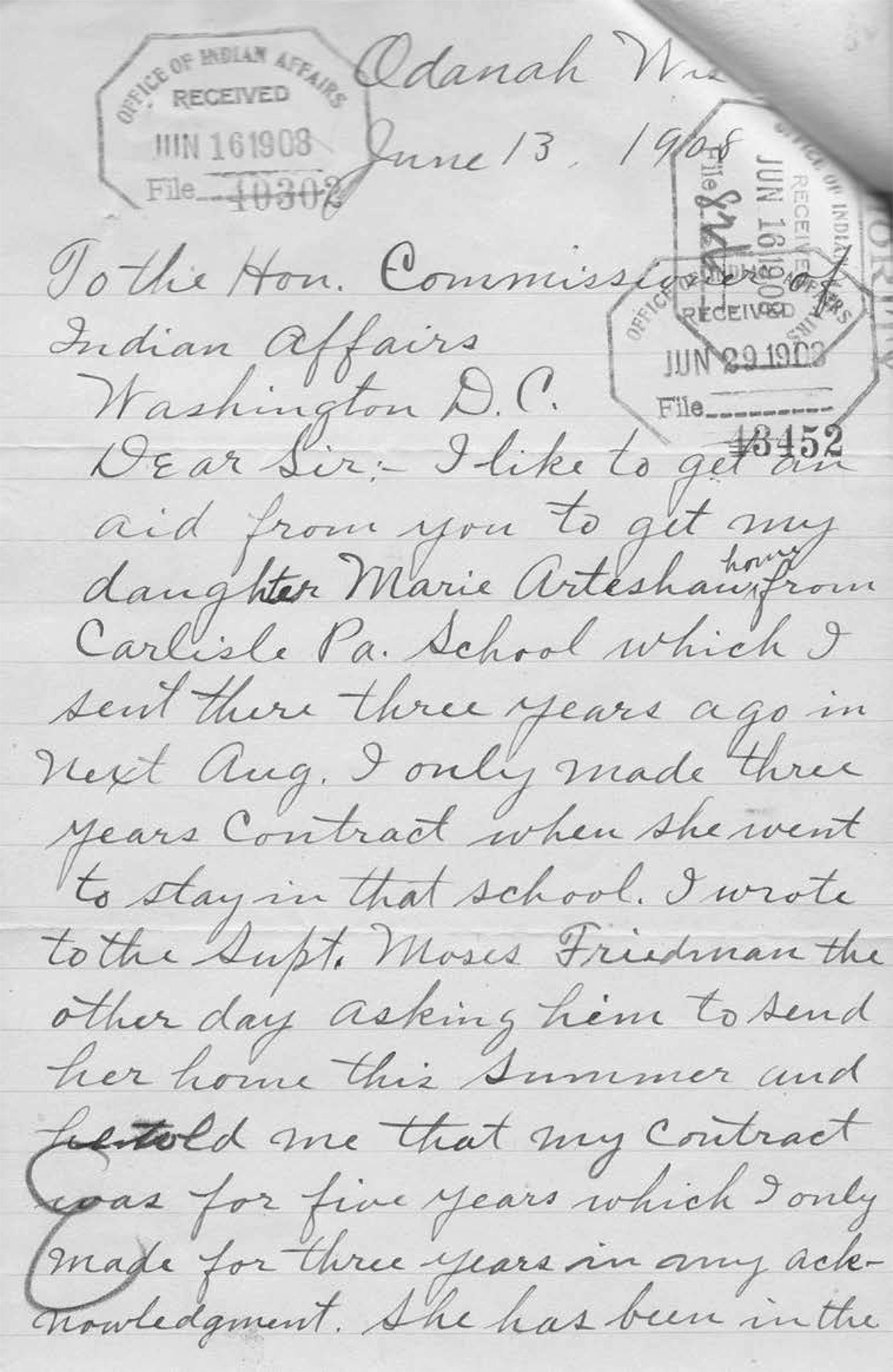

| Odanah, Wisconsin June 13, 1908 To the Hon. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Washington D.C. |

This is a letter from Theresa Green to the Office of Indian Affairs. |

| Dear Sir: I like to get an aid from you to get my daughter Marie Arteshaw home from Carlisle Pa. School Which I sent there three years ago in next Aug. I only made three years contract when she went to stay in that school. |

Theresa requests that the Office help her daughter, Marie Arteshaw, return home. Marie is currently a student at the Carlisle Indian School. |

| I wrote to the Supt. Moses Friedman the other day asking him to send her home this summer | Theresa wrote to the school, but the school refused her request. |

| and he told me that my contract was for five years which I only made for three years in any acknowledgment. | Theresa believes she signed a three-year contract, but the school insists she signed a five-year contract. |

| She has been in the Government schools since she was about five or six years old and she is pasted eighteen now and she wants to come home now and my-self I like to see her come home now. And that is the only child I have, so I am anxious to see her.

Your’s Truly |

Marie wants to come home, and Theresa is eager to see her daughter. |

Theresa Green, “Request for Marie Arteshaw to Return Home.” Three letters between Theresa Green and the office of Indian Affairs, 1908. National Archives and Records Administration.

Document Text |

Summary |

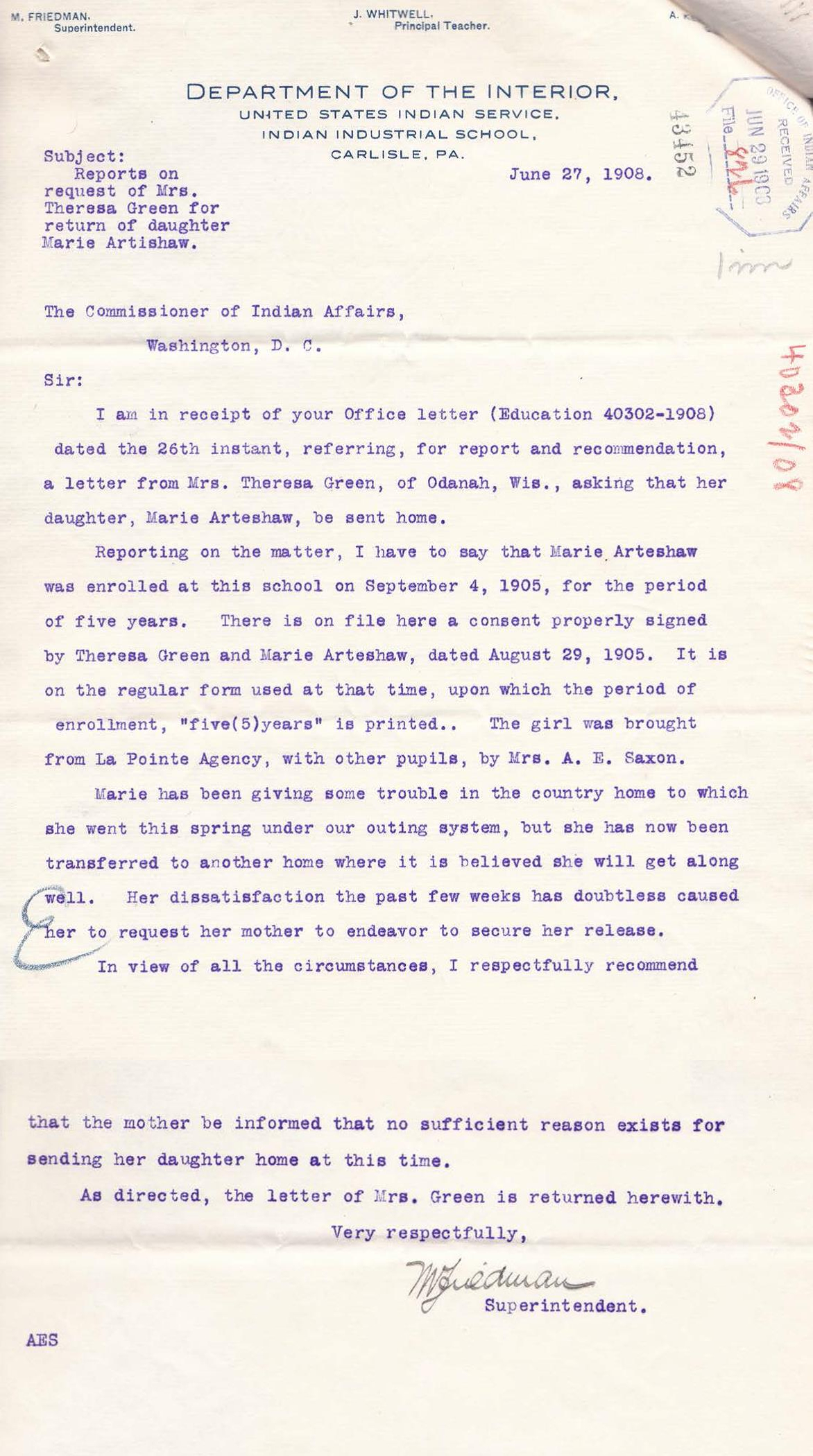

| Department of the Interior United States Indian Service Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, PA. Subject: Reports on request of Mrs. Theresa Green for return of daughter Marie Artishaw. June 27, 1908The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Washington, D.C. |

This is a letter from the superintendent of the Carlisle Indian School to the Office of Indian Affairs. |

| Sir: I am in receipt of your Office letter (Education 40302-1908) dated the 26th instant, referring, for report and recommendation, a letter from Mrs. Theresa Green, of Odanah, Wis., asking that her daughter, Marie Arteshaw, be sent home. |

The superintendent is providing a report to the Office regarding Theresa’s request that her daughter, Marie, be sent home. |

| Reporting on the matter, I have to say that Marie Arteshaw was enrolled at this school on September 4, 1905, for the period of five years. There is on file here a consent properly signed by Theresa Green and Marie Arteshaw, dated August 29, 1905. It is on the regular form used at that time, upon which the period of enrollment, “five(5)years” is printed. The girl was brought from La Pointe Agency, with other pupils, by Mrs. A. E. Saxon. | Marie enrolled at the school in 1905. She and her mother signed a contract stating she would be at the school for five years. |

| Marie has been giving some trouble in the country home to which she went this spring under our outing system, but she has now been transferred to another home where it is believed she will get along well. | Marie has recently been in trouble at the school, but the staff believes that her behavior may improve. |

| Her dissatisfaction the past few weeks has doubtless caused her to request her mother to endeavor to secure her release. | The superintendent thinks that Marie probably asked her mother if she could come home because she got in trouble. |

| In view of all circumstances, I respectfully recommend that the mother be informed that no sufficient reason exists for sending her daughter home at this time.

As directed, the letter of Mrs. Green is returned herewith. Very respectfully, |

For the above reasons, the superintendent recommends that Marie stay at the school because there is no good reason for her to leave. |

Friedman, Moses. Moses Friedman to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Carlisle, Pennsylvania. June 27, 1908. National Archives and Records Administration.

Document Text |

Summary |

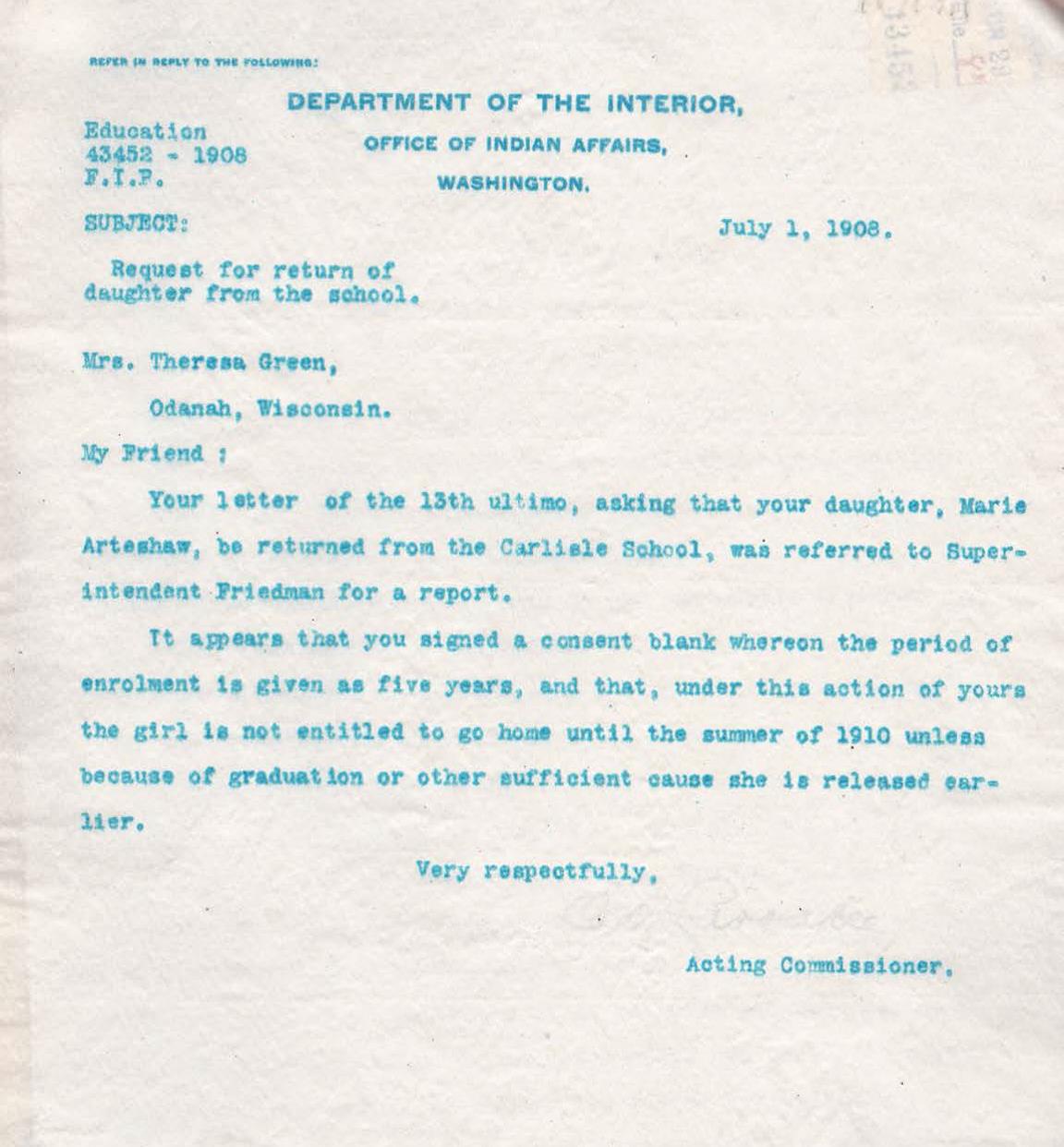

| Department of the Interior Office of Indian Affairs Washington July 1, 1908 Subject: Request for return of daughter from the school. |

This is a letter from the Office of Indian Affairs to Theresa Green. |

| Mrs. Theresa Green, Odanah, Wisconsin. My Friend: Your letter of the 13th ultimo, asking that your daughter, Marie Arteshaw, be returned from Carlise School was referred to Superintendent Friedman for a report. |

Theresa’s original letter was sent to the superintendent of the Carlisle School. He provided a report to the Office of Indian Affairs. |

| It appears that you signed a consent blank whereon the period of enrolment is given as five years, and that, under this action of yours the girl is not entitled to go home until the summer of 1910 unless because of graduation or other sufficient cause she is released earlier.

Very respectfully, |

Theresa signed a five-year contract, and her daughter is not allowed to leave until 1910, unless she graduates or has another reason for leaving early. Theresa’s request is denied. |

Acting Commissioner, Office of Indian Affairs. Acting Commissioner, Office of Indian Affairs to Theresa Green. Washington, D.C. July 1, 1908. National Archives and Records Administration.

Background

Between the 1880s and 1920s, thousands of Indigenous children left their homes on reservations to attend Indian boarding schools funded by the federal government. By 1902, there were twenty-five such schools across the country, serving roughly 3,000 female students each year. The most famous of these schools was the Carlisle Indian School, founded in 1879 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

The schools sought to “Americanize” the children. English was the only acceptable language and Christianity the only religion. All tribal languages, rituals, and customs were forbidden. Upon arrival, students underwent a makeover that included haircuts and uniforms. Female students were mostly taught domestic work: sewing, cleaning, cooking, ironing, and laundry. It was believed that female students would graduate, return home, and “elevate” their communities through an “American” approach to family life.

The experience was equally traumatic for parents. Formal education was rarely available on reservations. When parents resisted sending their children, government agents would withhold rations or involve police. During recruitment, some families would go into hiding or would bargain to send one child in exchange for keeping the rest at home. Parents were required to sign multi-year contracts, and efforts to break contracts consistently failed. Most parents could not afford to travel to the school and physically remove their children. Some desperate parents encouraged their children to run away when other options failed.

When families were finally reunited, it was difficult for life to return to normal. After years of being taught to reject their culture, children struggled to feel at home. Female graduates found the return particularly challenging because they were trained to do little more than housework. A few women found jobs as unskilled clerks in the Indian Bureau, but most remained unemployed after years of sacrifice and education.

About the Document

This set of documents includes three letters relating to Marie Arteshaw, a student at the Carlisle Indian School, in 1908. In the first letter, Theresa Green, a widowed mother from the Chippewa Nation, writes to the commissioner of Indian Affairs and asks that her daughter, Marie Arteshaw, be sent home from the Carlisle school. After receiving Theresa’s letter, the commissioner asked the superintendent of the school to provide a report in response to this request. The second letter in this set is the superintendent’s report to the commissioner. In the last letter, the commissioner responds to Theresa Green.

Additional records from the school help us to fill in the story. Theresa and Marie did sign a five-year contract. Their understanding of that document is unclear. Marie’s school record confirms she got into trouble in 1908. Marie stayed at Carlisle until graduation in 1910. Her final report states that she was qualified for work in four categories: housework, laundry, sewing, and cooking. A follow-up report three years later noted that she was married and living as a housewife in Wisconsin.

Vocabulary

- boarding school: A school that provides students with food and lodging.

- entitled: To have the right to do something.

- outing system: The process in Indian schools by which students would live with nearby families and contribute to work in the home and on the farm.

- reservation: Public land set aside for a specific use. Indian reservations were areas identified by the federal government for the Indigenous community.

- sufficient: Acceptable, adequate, or reasonable.

Discussion Questions

- Theresa Green tried twice to remove her daughter from the school and was denied both times. How might she have felt? What other options might have been open to her and Marie?

- The superintendent writes that Marie has been getting into trouble. Why might Marie have been acting up?

- What does the tone and length of the commissioner’s response to Theresa Green suggest about his attitude toward her and her request?

- Students could only leave the school if their contract ended, they graduated, or there was a “sufficient reason.” Theresa Green’s request is not a sufficient reason. Why do you think the rules were so strict and what does it say about the relationship between Indigenous people and the federal government?

Suggested Activities

- AP Government Connections:

- 4.4: Influence of Political Events on Ideology

- 4.8: Ideology & Policy-making

- 4.10: Ideology & Social Policy

- Compare the experiences of Marie and Theresa with those of Zitkala-Sa and her mother, who also grappled with the challenge of education in the Indigenous community.

- Many of the women in this unit benefitted from having parents who believed their daughter(s) should have a solid education. Compare Theresa Green’s story with those of Mary Church Terrell‘s parents, Ellen Swallow Richards’s parents, Clara Lemlich’s parents, and Jane Addams’s parents. How did race, culture, and class inform attitudes toward education and the options available to parents and their daughters?

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP