Clara Lemlich Shavelson was born in 1886 in Gorodok, Ukraine. She did not receive a formal education because there were no Jewish schools for girls. But Clara did not let this stop her. She borrowed books from neighbors and hid them in her attic. She was fascinated with Karl Marx and communism. By the time she was a teenager, Clara had formed her own beliefs about the challenges of working-class people.

When Clara was 17, her parents decided to move to America and escape the violence against Jews spreading in Europe. Within two weeks of arriving on New York’s Lower East Side, Clara was working in a garment factory. Because her father found it hard to find a permanent job, Clara was often the primary breadwinner for her family.

The garment industry in the early 1900s was growing. New inventions led to faster and cheaper production. Americans could now buy “ready made” clothes in stores and catalogs. Although the garment industry was almost exclusively owned and managed by men, the vast majority of its workers were young Jewish and Italian immigrant women. These women worked six to seven days a week for twelve to fourteen hours a day, with one bathroom break per day. The average wage was $2 per day. Workers often had to provide their own supplies, including sewing machines. When they were late or made a mistake, they were fined.

Clara described the work as “unbearable.” Like other young immigrants, she had hoped to take advantage of life in a big city. But she was too busy working to go to the theater, the beach, or the grand department stores that sold the very clothes she made.

Clara spent her little free time doing what she did best—teaching herself new things. After a long day of work, she would go to the public library to read or take a class at night school. Then, she would go home, eat a late dinner, and sleep for a few hours before starting again.

Through her studies, Clara realized the only way to change the lives of thousands of young women was to organize. Traditionally, unions ignored garment workers because the labor force was always changing. Most young women worked for a few years until they married. But Clara did not believe that this was a good excuse for not fighting.

Clara helped form a chapter of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. She spoke on street corners, organized meetings, and led strikes in several factories. She was constantly fired for her efforts. Each time she lost a job she found a new one and started to make trouble again. During one strike, Clara was arrested seventeen times, and the police broke six of her ribs. Within days, she was back on the picket line. She hid her bruises from her parents so they would not beg her to stop.

On November 22, 1909, a massive meeting of garment workers was held at New York City’s Cooper Union. Male leaders spoke for hours about the terrible work conditions. Clara became frustrated that they did not offer a solution. So, she walked up to the podium and spoke in Yiddish, the language spoken by most Jewish immigrants. She said, “I am one of those who suffers from the abuses described here, and I move that we go on a general strike.” The newspapers described her as an unknown girl, but the crowd recognized her as a leader who had been fighting for years. Her words were an inspiration.

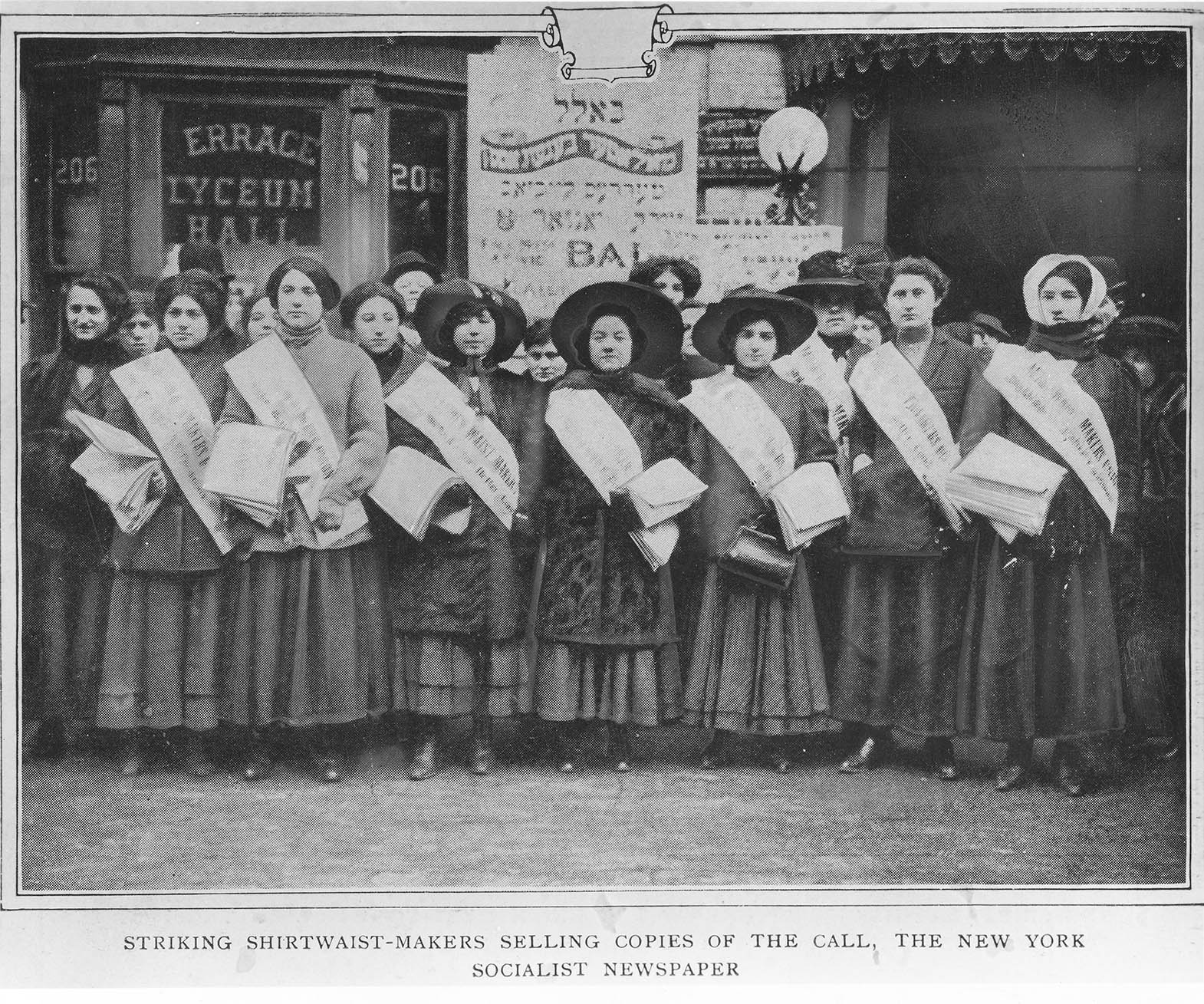

The next morning the garment industry went on strike. Within days, an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 young women refused to work. It was the largest organized strike in United States history to date. Similar strikes popped up in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, and other states, all inspired by the work of Clara and her colleagues.

Through the long, cold winter of 1909–10, Clara led picket lines, organized parades, and made speeches. Rich women became aware of the cause and helped to raise money and attract newspaper attention. As the public became aware, some factory owners felt pressure and offered shorter hours, better pay, and better conditions. By February 1910, many strikers could no longer afford to be unemployed. Most returned to work without any change in their circumstances.

Although the strike had improved conditions at some factories, it did not result in the widespread reform Clara and her fellow workers sought. Only one year later, on March 25, 1911, a lack of safety precautions lead to a fire in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York. 146 workers, mostly young immigrant women, died.

Clara could not return to work like many of the other women who had gone on strike. She had been blacklisted from the industry. Instead, she found paid work as an organizer. She spoke out about women’s suffrage, education, work conditions, and more.

During one strike, Clara was arrested seventeen times, and the police broke six of her ribs. Within days, she was back on the picket line.

In 1913, Clara married Joe Shavelson. They had three children and moved to Brownsville, Brooklyn. There she organized housewives and mothers. Together, they boycotted stores that charged too much for food, protested landlords who increased rents, and fought for better access to schools. In the 1930s, she organized a meat boycott that forced 4,500 New York City butchers to temporarily shut down until they lowered their prices. The movement spread to other cities, including Detroit and Los Angeles.

Clara’s husband died in 1951. That same year, she had to testify in Congress before the House Un-American Activities Committee because of her connections to the Communist Party and her anti-war beliefs. She and her children remained under government surveillance for two decades.

By her 80s, Clara was living in a nursing home. She helped the staff form a union and encouraged people at the home to boycott certain businesses because of unfair labor practices. She died at the age of 96 in 1982, working as an activist until the end of her life.

Vocabulary

- breadwinner: The person in a family who is responsible for most of the family’s income.

- communism: A political system in which all goods and items of value are distributed equally.

- garment: An article of clothing.

- House Un-American Activities Committee: A committee of the House of Representatives that investigated individuals and organizations suspected of being disloyal to the United States.

- Karl Marx: A German political theorist who promoted the ideals of communism and wrote The Communist Manifesto in 1848.

- picket line: A line of people protesting; often used during strikes.

- Yiddish: The language spoken by most Eastern European Jewish immigrants in this era.

Discussion Questions

- How did Clara’s experiences in Ukraine affect her life and actions in America?

- What challenges did young immigrant women face in the garment industry, and what options did they have for changing their situation?

- What made Clara’s speech at Cooper Union so powerful?

- Clara is best known for her speech at Cooper Union. Why is it important to study her entire life, including what happened after she left the garment industry?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 7.4: The Progressives

- Lesson Plan: In this lesson designed for fourth grade, students will learn about Clara Lemlich, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, and labor union activism in the early 20th century.

- Strikes were an important technique used by labor activists to demand change in the workplace. Compare the story of New York City’s garment workers with that of laundry workers in El Paso, Texas.

- Clara made her famous speech during a mass meeting at Cooper Union in New York City. Look at the advertisement for the feminist mass meeting (also held at Cooper Union) and consider how and why mass meetings were an important tool used by activists and social reformers in this era.

- Compare Clara’s life story with that of Emma Goldman, another Russian Jewish immigrant who was politically active in New York City.

Themes

IMMIGRATION, MIGRATION, AND SETTLEMENT; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; WORK, LABOR, AND ECONOMY