Ellen Swallow was born in Massachusetts in 1842. Her parents were former teachers who homeschooled their daughter because they did not believe the nearby primary school offered a strong enough education for girls. When Ellen was a teenager, the family moved to a different town so that Ellen could attend one of the few high schools in the region accepting female students.

Ellen learned to work hard at a young age. In high school, she excelled in math, science, and foreign languages. She also managed accounting and inventory for her parents’ grocery store. After graduation, her family could not afford to send her to college. Ellen did not let this stop her. She took jobs in nursing, housekeeping, and teaching. By the age of 26, she had saved the $300 needed to enroll at Vassar College, a women’s college in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Although Ellen was drawn to many subjects within the sciences, she majored in chemistry because it had practical applications to daily life. This desire to connect scientific research with the real world became a key characteristic of her impressive career.

Ellen graduated from Vassar in 1870 with the goal of obtaining paid work in a chemical lab. She applied to companies across the United States, but none wanted to hire a woman. After turning Ellen down, one lab suggested applying to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Although MIT was not yet a co-educational college, Ellen applied. The admissions board was impressed with Ellen’s education, but board members were afraid to publicly open the doors to women. As a compromise, they admitted Ellen as a “special” student. She was not charged tuition nor placed on any official rosters, but in all other respects, she was the first female student at MIT.

Ellen was often the odd one out at MIT. Her status as a “special student” denied her some of the mentoring opportunities afforded her male counterparts. She rarely had peers in whom she could confide, so she turned to her work. She took every class available to her. The work ethic she developed as a child shaped her approach to being a pioneer in her field. By doing excellent work, Ellen proved she deserved a seat at the table.

As a research assistant, Ellen was in charge of a project examining water sewage for the Massachusetts Board of Health. She earned an international reputation as an expert in water quality analysis, and her outcomes shaped the state’s new water quality standards. In 1873, Ellen officially graduated from MIT with her second undergraduate degree.

While Ellen was a student, an instructor in the MIT mineralogy department named Robert H. Richards asked her to help translate a German text he needed for his research. The two quickly formed a working and personal relationship. In 1873, Robert proposed to Ellen as they worked side by side in his lab. Ellen waited two years before saying yes. She wanted to be sure their marriage would never stand in the way of her work. Robert and Ellen married in June 1875 and immediately went on honeymoon. They spent the entire trip studying the mines of Nova Scotia—and brought Robert’s students with them to join in the work. Ellen and Robert never had children and dedicated their marriage to supporting one another’s research.

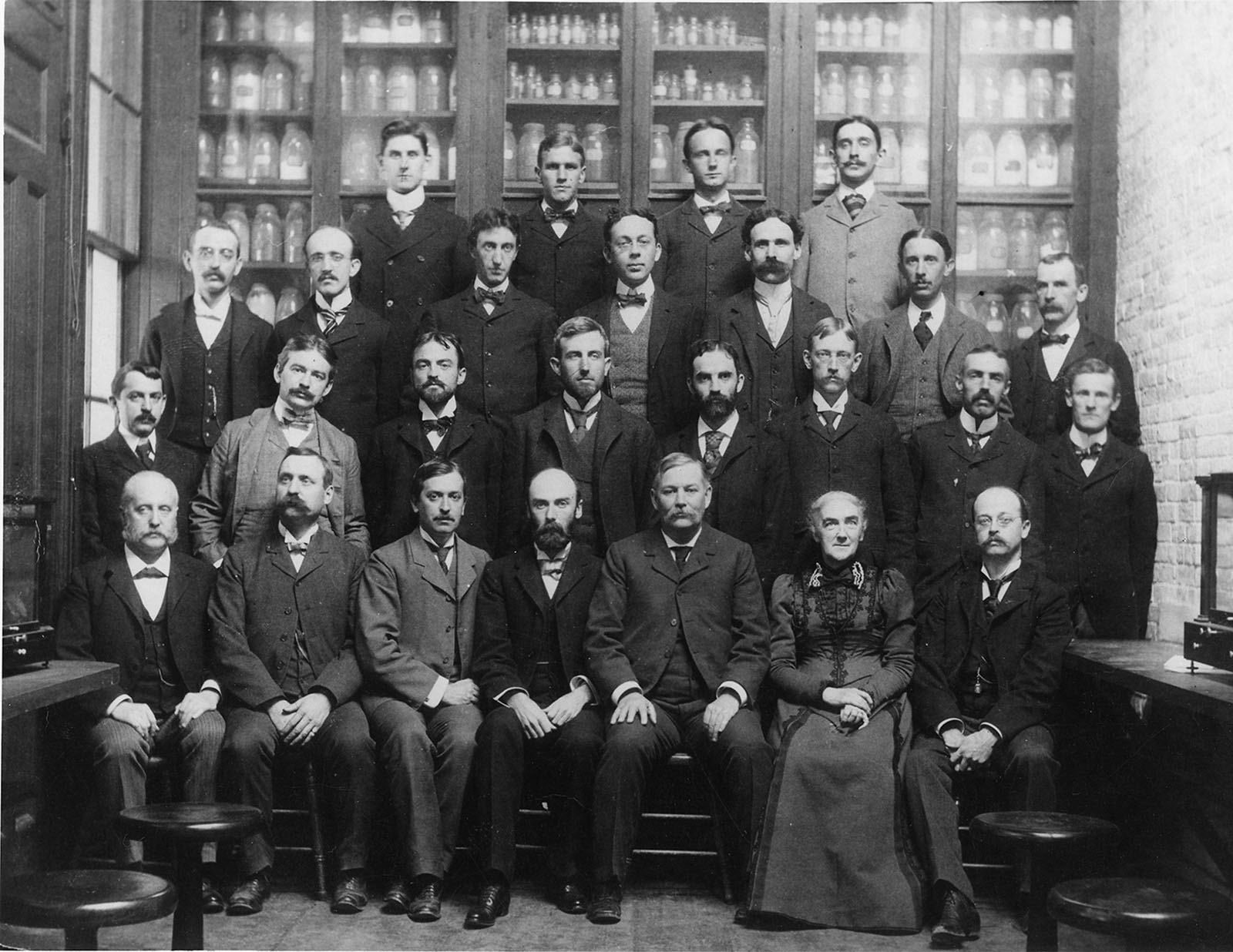

Ellen wished to earn her Ph.D. at MIT, but the faculty would not allow a woman to do so. As Head of the Mineralogy Department, Robert made enough money to support them both. This allowed Ellen to pursue a career in the sciences without pay for many years. In 1876, she raised enough money to open the Women’s Laboratory at MIT. It was a space where women could conduct in-depth research in chemistry, biology, mineralogy, and other scientific areas. Ellen served as an instructor. In 1883, MIT officially opened its doors to women and allowed them to conduct research alongside men. MIT closed the Women’s Laboratory and offered Ellen an official position as an instructor of sanitary chemistry, which included the study of air, water, human waste, and sewage in connection with public health and disease. It was a role she held until her death.

Ellen was a brilliant and industrious scientist who not only conducted research, but also established programs and organizations related to her work. She wrote most of MIT’s curriculum for sanitary chemistry and served as the program’s primary instructor. She contributed to the creation of the Seaside Laboratory, which became the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole. She was a vocal supporter of women’s education and helped found an organization that would become the American Association of University Women. She conducted a multi-year study into Massachusetts’s drinking water and studied over 20,000 water samples in the process.

Ellen majored in chemistry because it had practical applications to daily life. This desire to connect scientific research with the real world became a key characteristic of her impressive career.

But Ellen was most passionate about the connections between science and the daily life of housewives. Ellen was a pioneer in the home economics movement. She knew that the more housewives understood the principles of sanitation and germs, the more they could prevent disease and infection at home. Ellen viewed housewives as a critical unpaid labor force. From her perspective, if paid workers received on-the-job training, housewives should receive an education in the science and economics of the home. Ellen wrote that a good housewife was constantly asking herself what could be better, healthier, cleaner, or more effective in her home. The answers to those questions could often be found in science. Cooking and cleaning were merely practical applications of chemistry.

In 1890, Ellen established The New England Kitchen of Boston, which offered cooking demonstrations, instruction on proper housekeeping techniques, and nutritious, science-based meals for visitors. In 1894, her work was replicated in a demonstration kitchen at the Chicago World’s Fair, where Ellen’s research reached people from across the globe.

Ellen’s work in the field of home economics had a lasting impact. She founded and served as the president of the American Home Economics Association. The organization’s members were effective advocates for improving women’s access to information and formal education opportunities.

In 1910, Ellen received something she wanted, but had long been denied. Smith College, a women’s college, awarded her an honorary Ph.D. in recognition of her life’s work. Less than a year later, on March 30, 1911, she died of a heart attack. She was still a member of MIT’s faculty and actively conducting research until the day she died.

Vocabulary

- co-educational college: A college that accepts both men and women students.

- home economics: The study of the science and economics of the home, including cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children.

- industrious: Diligent.

- mineralogy: The science of minerals.

- sanitary chemistry: The study of air, water, human waste, and sewage in connection with public health and disease.

- water quality: The healthiness of water.

- water sewage: Dirty water from toilets, sinks, and other sewer systems.

Discussion Questions

- How was Ellen’s approach to work and education formed by the experiences of her youth?

- What does Ellen’s hesitance to marry Robert Richards tell us about her personality and goals? How did their marriage ultimately shape her career?

- Ellen was a talented researcher, but the last years of her life were mostly spent outside of the lab, advocating for the home economics movement. Why do you think this was an important cause for Ellen and how did it connect to her training as a scientist?

Suggested Activities

- Lesson Plan: In this lesson designed for fourth grade, students will learn about the life and work of Ellen Swallow Richards.

- Connect this life story to the Course of Instruction from the Agricultural College of Utah. How did the professionalization of housework help to break down barriers between higher education, scientific research, and the domestic sphere?

- How did science and technology shape life at home? Pair Ellen’s life story with the home appliance advertisement from Life magazine.

- Study the impact of higher education on modern women. Read Ellen’s life story in conjunction with the life stories of Jane Addams and Mary Church Terrell, who also graduated from college. How did their education shape their careers and personal lives?

- Consider how marriage shaped many women’s lives in this era, and how Ellen Swallow Richards’s marriage broke from tradition. Compare Ellen’s life story with the depiction of domestic life in the advertisement in Life magazine and the suffrage poster “Together for Home and Family”.

Themes

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND MEDICINE; AMERICAN CULTURE; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE