Emily Warren was born in 1843 in Cold Spring, New York. The Warrens were an influential family, and Emily’s father was a politician who served in the New York State Assembly. Emily was one of 12 children. Her parents’ wealth allowed Emily to attend a prestigious all-girls school, the Georgetown Visitation Convent.

Gouverneur K. Warren, Emily’s brother, served in the Union Army during the Civil War. He participated in the Battle of Gettysburg. Shortly after, he invited Emily, now a young woman, to visit him at the camp. During this visit, she met Colonel Washington Roebling. Emily and Washington fell in love and married in 1865. The Roeblings started their married life apart, as Washington was still an active member of the military.

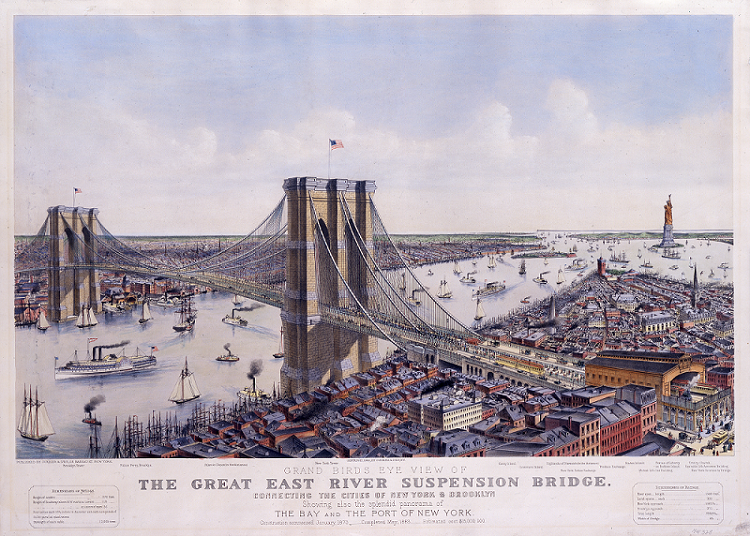

Emily’s new father-in-law, John Augustus Roebling, was a world-famous architect who specialized in suspension bridges. In 1867, he received his most ambitious assignment yet—to build a 1.1-mile (1.8-km) bridge across the East River between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Nobody had ever built a suspension bridge of this length before.

In 1867, the Roeblings went on a belated honeymoon to Europe. Their trip was not a typical honeymoon. John Roebling asked the young couple to conduct research for his new bridge project. They visited construction sites and met with engineers to learn about the latest bridge-building techniques. For example, they learned about caissons, pressurized watertight chambers that were used to build underwater foundations for bridges.

Emily was pregnant when she and Washington left for their honeymoon. She gave birth to their son, John Roebling II, in Germany on November 21, 1867. When they returned to the United States, the Roeblings settled in Brooklyn, near the construction site for the bridge.

In 1869, John Roebling got hurt in an accident at the Brooklyn Bridge construction site. He contracted tetanus from his injury and died a month later. Washington, who had been working alongside his father for only a few years, was now in charge of completing the Brooklyn Bridge. He became the project’s chief engineer.

Washington Roebling regularly joined his workers underwater in the caissons. What people did not know at the time was that working under compression was incredibly dangerous. Many workers became ill with what’s known as decompression sickness, or caisson disease. Washington got so sick that he was almost paralyzed. For years, he was so sensitive to bright lights and loud noises that he barely left his home.

As her husband was no longer able to oversee the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in person, Emily took over that responsibility. While Washington officially remained the chief engineer and oversaw some work from home through a telescope, it was Emily who visited the construction site every day, attended board meetings, and managed the project. She studied everything she possibly could about bridge construction.

Emily tried to keep her involvement a secret during the decade she took on the duties of chief engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge. She did not want the public to know about her husband’s illness and worried he would lose the contract to build the bridge. In private, she made it clear that the Roebling family would forever be associated with the Brooklyn Bridge because of her work and advocacy.

“I have more brains, common sense, and know-how generally than any two engineers civil or uncivil that I have ever met.”

The Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883. At the time, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world. Emily was the very first person to walk across it. Her work on the bridge had not gone unnoticed. Congressman Abram Hewitt from New York praised her at the official opening of the Brooklyn Bridge.

In the decade following the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge, Emily spent most of her time with her family. Her son, John, had a heart condition, which she closely monitored. When he started college at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, she and Washington moved with him.

Emily focused on her own ambitions after her son graduated from college, married, and moved to Arizona. She and Washington moved to Trenton, New Jersey, where the Roebling family owned a wire rope factory. She joined various women’s clubs in Trenton and New York City. She was a particularly active member of the Federation of Women’s Clubs, where she helped create materials for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Emily again traveled to Europe in 1896. Washington was still ill, so she traveled by herself. In London, Queen Victoria received her at court. In St. Petersburg, she attended the coronation of Czar Nicholas II of Russia.

When Emily came back to the United States, she traveled across the country to give lectures about her experiences in Russia for the Federation of Women’s Clubs. Emily also became an active member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and was even nominated to become the president of the organization in 1901. She declined the invitation because of health problems.

Through her volunteer and charity work, Emily became increasingly interested in the fight for women’s equality. She obtained a Women’s Law Course certificate from New York University in 1899. This was a special program for women for whom knowledge of the law could be helpful in their work. Many wealthy women audited the class, but Emily insisted on taking the exams.

The program offered an essay contest, which Emily won. Her winning essay was read aloud at the graduation ceremony. In her essay, Emily advocated for women’s suffrage, stating that women should have “the possible rights given them under the Fourteenth Amendment.” She also criticized how married women lacked property rights under coverture.

During the next few years, Emily traveled across the country to give speeches to women’s clubs. She advocated for women’s suffrage and social services for the poor and encouraged women to study law.

Emily Warren Roebling died on February 28, 1903, from stomach cancer. In 2018, New York City renamed a street in Brooklyn in her honor.

Vocabulary

- audit: To attend a class without receiving official credits.

- caisson: Watertight compound for underwater construction.

- compression: The act of creating higher air pressure.

- coronation: A ceremony where a monarch is crowned.

- coverture: A common law practice where women fell under the legal and economic oversight of their husbands upon marriage.

- Daughters of the American Revolution: Women’s organization that promotes and preserves American history. All its members are descendants of soldiers or supporters of the Patriots during the American Revolution.

- Federation of Women’s Clubs: Women’s organization consisting of thousands of local chapters, whose goal it is to improve local communities.

- paralyzed: Unable to move.

- suspension bridge: A bridge that has overhead cables supporting the roadway.

- tetanus: A severe bacterial infection.

Discussion Questions

- What contributions did Emily make to the Brooklyn Bridge?

- Why did she try to keep her role on the bridge project a secret? What does that say about the expectations of women in society at the time?

- How might Emily’s experience with the bridge have influenced her later activism for women’s rights?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 6.11: Reform in the Gilded Age

- Help students understand how novel the suspension bridge was to regular New Yorkers. Pair this life story with the story of how P.T. Barnum alleviated citizens’ fears about the safety of the Brooklyn Bridge.

- Emily Warren Roebling did not have a formal education as an engineer. Pair her life story with that of Florence Merriam Bailey, another woman who built a career for herself in STEM. What opportunities did these women have because of their class? What restrictions did they face in their career paths?

- Consider how industrialization changed the lives of women of different races and social classes during this time period. Combine this life story with a document about factory conditions, an image of shop girls, an article about a labor strike in Atlanta, photographs of the Vanderbilt Costume Ball and the life story of Leonora Barry.

- Explore how members of women’s clubs pushed for social change. Teach this research alongside a speech from the first Black women’s club convention.

Themes

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND MEDICINE