This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Victoria Claflin was born on September 23, 1838, in Homer, Ohio. Homer is a small town in a rural community. Victoria had nine siblings but was particularly close with her youngest sister, Tennessee.

The Claflin family was poor. They traveled around the country selling “miracle cures” for common health problems. They claimed their products were medicine, but most of them were just bottles of alcohol that did not cure anything. While the family took their “medicine show” from town to town, young Victoria contributed to their income as a fortune teller.

When she was 15 years old, Victoria left her family to marry Canning Woodhull. He sold patent medicine like her family and presented himself as a doctor. There were no exams or licenses for doctors at the time, so it was easy to pretend to be an expert. Tragically, her new life as a married woman was not much better than her childhood. Canning was a physically abusive alcoholic who cheated on Victoria and failed to support his family financially. They had a son, Byron, and a daughter, Zulu. Byron had an intellectual disability, which Victoria believed was caused by his father’s drinking problem.

Victoria divorced Canning Woodhull in 1864. Divorced women were often treated as outcasts in society at the time. It was not socially acceptable for wives to leave their husbands, especially if they had children together. Many women stayed in bad marriages because they did not have the option to leave. Victoria believed in “free love,” which to her meant that someone should only stay in a relationship if they were happy.

After the Civil War, Victoria met Colonel James Harvey Blood. Although there is no marriage record, they both said they got married in 1866. James was a much better husband than Canning. He was kind, educated, and believed in the idea of free love just like Victoria.

Victoria, James, and Victoria’s two children moved to New York City in 1868, where they lived with Victoria’s sister, Tennessee. Victoria started a salon, which was a space where people could gather to learn about and discuss a variety of topics. Through her salon, she met many influential New Yorkers and she became a well-known conversationalist.

Victoria and Tennessee made money as spiritual advisors. This was similar to the work they did as child fortune tellers. One of their clients was the recently widowed millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt, who they allegedly helped connect with his dead wife. They also advised him on financial decisions.

They likely received financial advice from Vanderbilt in return. Victoria believed that financial success was the key to a woman’s independence, even more so than the right to vote. The two sisters used the knowledge they gained from Vanderbilt to invest in stocks. In 1870 they were the first women in New York to open their own brokerage firm. Woodhull, Claflin, & Company was a firm exclusively for female clients. A sign in their window stated: “Gentlemen will state their business and then retire at once.” Victoria and Tennessee recognized that many women wanted to invest their money, but male brokers did not take women seriously. The sisters’ business was a financial success.

“The American nation, in its march onward and upward, can not publicly choke the intellectual and political activity of half its citizens by narrow statutes.”

Three months after starting their business, Victoria and Tennessee used their investment profits to launch a newspaper called Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. They published articles arguing for equal treatment of women, including giving women the right to vote and reforming labor practices. The newspaper was also known for addressing topics that were considered taboo at the time, like sex education and spiritualism. Many critics attacked their beliefs, including Victoria’s support of free love.

Victoria’s work for gender equality led to a leadership role in the women’s suffrage movement. She testified in Congress that she believed women already had the right to vote, as the 15th amendment granted all citizens voting rights. This gave her a national platform as newspapers across the country published her speech.

In 1871, Victoria announced that she was running for president of the United States. Although women did not have the right to vote, it was not illegal for women to run for office. Victoria became the official nominee of the Equal Rights Party. She was the first woman to run for president. Historians argue that it was more symbolic than a viable candidacy. Victoria did not receive a significant number of votes and was not yet 35 years old, the minimum age for the presidency according to the Constitution.

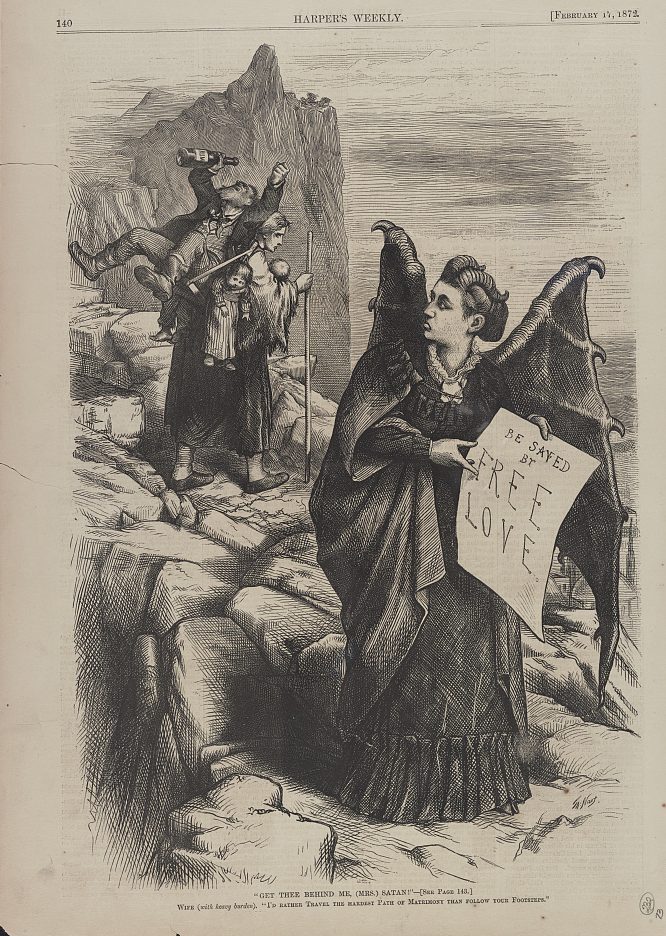

The press attacked Victoria for her activism and belief in free love throughout the election. In 1872, the famous political cartoonist Thomas Nast depicted Victoria in one of his cartoons as Satan’s wife advocating for free love. In the background, a struggling wife rejects the free love movement. She would rather climb the steep hill ahead of her, while carrying two young children and an alcoholic husband, than be associated with Victoria. Her presidential campaign had elevated her profile nationally but had made her infamous rather than admired.

Victoria learned that one of her strongest critics, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, cheated on his wife with a married woman in their parish. Victoria thought it was hypocritical that men had extramarital affairs while attacking women for wanting sexual freedom. Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly covered the story in detail. U.S. Marshals arrested Victoria, her sister, and her husband on charges of obscenity. The stories about the affair were detailed and considered offensive. It was illegal to send immoral content through the mail. The courts acquitted all three of them on a technicality after they had been imprisoned for six months.

The Beecher affair changed Victoria’s life significantly. She and her husband paid half a million dollars in bail and went bankrupt. They divorced in 1876. That same year, she stopped publishing Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. The case had also negatively affected Victoria’s reputation in the suffrage movement. Other leaders of the movement considered her to be too radical. Victoria continued to give public lectures with a focus on women’s rights within marriage.

Victoria and Tennessee moved to England in 1877, where Victoria continued her career as a lecturer. She met her third husband, John Biddulph Martin, at one of her lectures. They married in 1883. She had used the name Victoria Woodhull since her first marriage. After marrying John, she changed it to Victoria Woodhull Martin.

As she got older, Victoria’s views grew less radical, but she was still active in the suffrage movement in Great Britain. She returned to the newspaper business. She published a weekly newspaper for three years that focused on equal rights called The Humanitarian. Victoria retired after her husband passed away in 1901 and moved to the English countryside.

Victoria Woodhull died on June 9, 1927, at the age of 88.

Vocabulary

- bail: Money an arrested person pays to the court to be released from jail and sometimes used as a guarantee they will attend trial.

- bankrupt: A person who is unable to pay outstanding debts.

- brokerage firm: Business that buys and sells stocks on behalf of clients.

- conversationalist: Someone who is good at or fond of engaging in conversation.

- extramarital affairs: Sexual relationships between a married person and someone who is not their spouse.

- hypocritical: Acting in a way that is the opposite of someone’s beliefs or opinions.

- obscenity: Something that is offensive or immoral.

- radicalism: Extreme behavior and beliefs.

- patent medicine: Substance sold as medicine but not prescribed by a doctor.

- spiritual advisors: People who believe they can communicate with the dead.

Discussion Questions

- How did Victoria Woodhull’s childhood and first marriage influence her beliefs about women’s rights?

- What was free love and why was this a particularly important issue for Victoria?

- What were Victoria’s beliefs about the importance of financial independence? How did this opinion inform her work and activism?

- Why did Victoria run for President? What message did she want to send about women’s suffrage? Why do historians debate the significance of her run for office?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connections:

- 6.6: The Rise of Capitalism

- 6.11: Reform in the Gilded Age

- AP Government Connection: 5.4 & 5.5: Third Parties

- Analyze the cartoon by Thomas Nast. How does he portray Victoria Woodhull?

- Victoria Woodhull was arrested for obscenity under the Comstock Act. Pair this life story with the resource on the Comstock Act to consider how this law shaped women’s lives and ability to advocate for change.

- For a larger lesson on the fight for women’s suffrage during this time period, combine this life story with Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s article on suffrage, a speech from the first Black women’s club convention, Minor v. Happersett, and the life stories of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Abigail Scott Duniway.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; POWER AND POLITICS