Document Text |

Summary |

| MINOR

v. HAPPERSETT. October Term, 1874 |

|

| The question is presented in this case, whether, since the adoption of the fourteenth amendment, a woman, who is a citizen of the United States and of the State of Missouri, is a voter in that State, notwithstanding the provision of the constitution and laws of the State, which confine the right of suffrage to men alone. We might, perhaps, decide the case upon other grounds, but this question is fairly made. From the opinion we find that it was the only one decided in the court below, and it is the only one which has been argued here. The case was undoubtedly brought to this court for the sole purpose of having that question decided by us, and in view of the evident propriety there is of having it settled, so far as it can be by such a decision, we have concluded to waive all other considerations and proceed at once to its determination.

(…) |

This case asks us to determine if women have the right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment. |

| There is no doubt that women may be citizens. They are persons, and by the fourteenth amendment ‘all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof’ are expressly declared to be ‘citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.’ But, in our opinion, it did not need this amendment to give them that position.

(…) |

Women have always been citizens of the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment says they are citizens but this was not necessary. |

| The amendment did not add to the privileges and immunities of a citizen. It simply furnished an additional guaranty for the protection of such as he already had. No new voters were necessarily made by it. Indirectly it may have had that effect, because it may have increased the number of citizens entitled to suffrage under the constitution and laws of the States, but it operates for this purpose, if at all, through the States and the State laws, and not directly upon the citizen. | The amendment did not change the rights and privileges of citizens. It just confirmed by law the rights citizens already had. If people received the right to vote, it is because the amendment changed the rights of citizenship at the state level, not at the federal level. |

| It is clear, therefore, we think, that the Constitution has not added the right of suffrage to the privileges and immunities of citizenship as they existed at the time it was adopted. This makes it proper to inquire whether suffrage was coextensive with the citizenship of the States at the time of its adoption. If it was, then it may with force be argued that suffrage was one of the rights which belonged to citizenship, and in the enjoyment of which every citizen must be protected. But if it was not, the contrary may with propriety be assumed.

(…) |

We think it is clear that the amendment did not give anyone the right to vote. This means that we should examine if states gave every citizen the right to vote before the amendment was passed. |

| In this condition of the law in respect to suffrage in the several States it cannot for a moment be doubted that if it had been intended to make all citizens of the United States voters, the framers of the Constitution would not have left it to implication. So important a change in the condition of citizenship as it actually existed, if intended, would have been expressly declared.

(…) |

If the writers of the Constitution wanted every citizen to vote, they would have made that clear in the Constitution. |

| Certainly, if the courts can consider any question settled, this is one. For nearly ninety years the people have acted upon the idea that the Constitution, when it conferred citizenship, did not necessarily confer the right of suffrage. If uniform practice long continued can settle the construction of so important an instrument as the Constitution of the United States confessedly is, most certainly it has been done here. Our province is to decide what the law is, not to declare what it should be. | The answer to this question is clear. The Constitution does not grant the right to vote to every citizen. Our job is to determine what the law is, not what it should be. |

| We have given this case the careful consideration its importance demands. If the law is wrong, it ought to be changed; but the power for that is not with us. The arguments addressed to us bearing upon such a view of the subject may perhaps be sufficient to induce those having the power, to make the alteration, but they ought not to be permitted to influence our judgment in determining the present rights of the parties now litigating before us. No argument as to woman’s need of suffrage can be considered. We can only act upon her rights as they exist. It is not for us to look at the hardship of withholding. Our duty is at an end if we find it is within the power of a State to withhold. | This is an important case and we have considered it carefully. If the law is unfair, it should be changed. But women do not have the right to vote under the current laws. |

| Being unanimously of the opinion that the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon any one, and that the constitutions and laws of the several States which commit that important trust to men alone are not necessarily void, we

AFFIRM THE JUDGMENT. |

We all agree that the Constitution does not give women the right to vote. |

Minor v. Happersett, 1874. Cornell Law School.

Background

The 14th Amendment guarantees everyone in the United States equal treatment under the law. The 15th Amendment gave voting rights to all male U.S. citizens. While it did not specifically say women could vote, it did not explicitly exclude women from the vote either. Following the ratification of these two post-Civil War amendments, suffragists used them to argue that their right to vote was guaranteed by the Constitution. Many of them believed that pointing to these amendments and using the court system was a strong strategy. They thought that the right case would force the courts to declare that denying women the right to vote was unconstitutional.

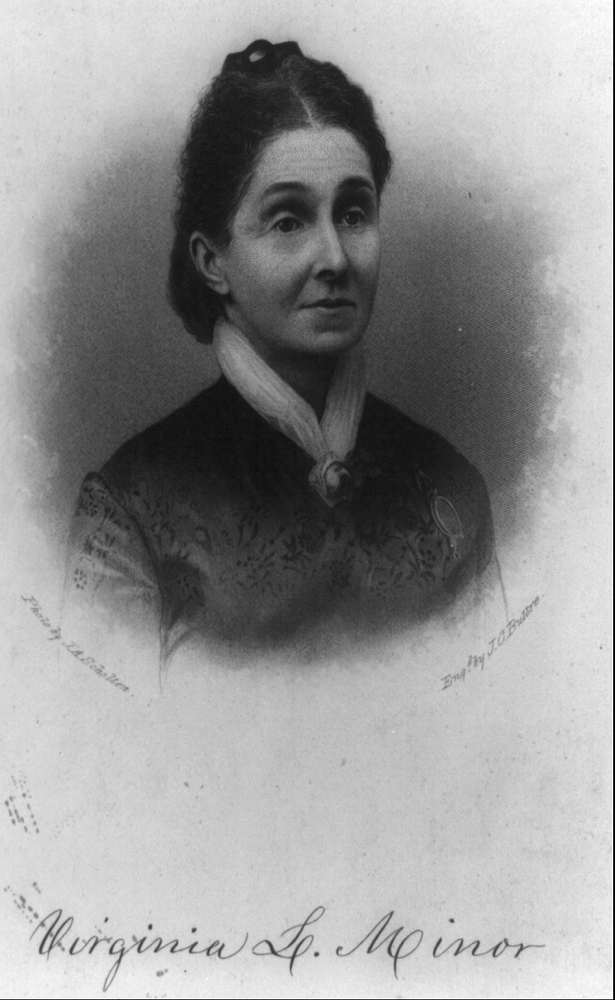

Virginia Minor was the president of the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri. In 1872, she tried to register to vote in St. Louis with the hope of taking her case to court. As predicted, the official refused to let her register. His name was Reese Happersett. In response to the refusal, Virginia and her husband sued the registrar for denying her “privileges and immunities of citizenship.” Virginia had to sue with her husband because Missouri law did not allow women to sue in court. The Minors lost the case in the local courts and appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

About the Document

This excerpt is from the majority opinion of the Minor v. Happersett Supreme Court case. It was written by Chief Justice Morrison R. Wait. The decision was unanimous. The court ruled that women were not allowed to vote under their interpretation of the Constitution. The justices believed that the rights to determine who could vote were to be determined by the states. Furthermore, they argued that if the writers of the Constitution would have wanted women to vote, they would have written it into the Constitution. Voting was a privilege, not a right, and therefore not all citizens were given the vote.

Because of this decision, women suffrage activists lost hope that the courts would extend voting rights to women. Since the Supreme Court ruled that the states had the power to determine who could vote, suffragists would have to secure the women’s vote with a constitutional amendment. For the next several decades, suffragists focused on this strategy. In 1920, the ratification of the 19th Amendment confirmed that the right to vote could not be denied based on gender.

Vocabulary

- affirm: To state that something is true.

- alteration: A change.

- coextensive: On the same level of importance.

- confine: To restrict something to a certain group.

- immunities: Freedoms from something bad.

- implication: A conclusion or consequence of something.

- jurisdiction: Area in which a particular court has authority.

- litigating: To take legal action; go to court.

- majority opinion: Explanation of the decision made by the majority of the justices in a Supreme Court case, written by one of the justices.

- privileges: Special rights or advantages belonging to a specific group of people.

- propriety: Something that is appropriate.

- province: Area of responsibility.

- provision: Making something available to people who want it.

- suffrage: The right to vote.

- unanimous: Fully in agreement.

- uniform: Standard.

- void: Invalid.

Discussion Questions

- What reasons does the Supreme Court provide for their decision in the Minor v. Happersett case?

- Virginia Minor knew that she would not be allowed to register to vote. Why did she try to do it anyway? How could this strategy be effective from the perspective of activists?

- All nine members of the Supreme Court were men during the Minor case. (Only in 1981, with the appointment of Sandra Day O’Connor, would the Supreme Court have its first female justice.) How do you think the gender makeup of the Supreme Court in 1874 influenced this decision?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 6.11: Reform in the Gilded Age

- Reflect on how the Supreme Court is influenced by changes in American Society. Read Section 1 from the Fourteenth Amendment and the Fifteenth Amendment. Ask students to write their own opinion in this case, based on these two amendments.

- Examine how the Supreme Court has affected women’s rights by pairing this resource with Muller v. Oregon, Goesaert v. Cleary, Loving v. Virginia, and Roe v. Wade.

- For a larger lesson on the fight for women’s suffrage during this time period, combine this life story with an article on suffrage by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a speech from the first Black women’s club convention, and the life stories of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Abigail Scott Duniway, and Victoria Woodhull.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE