Document Text |

Summary |

| It is with especial joy and pride that I welcome you all to this, our first conference. It is only recently that women have waked up to the importance of meeting in council and great as has been the advantage to women generally, and important as it is and has been that they should confer, the necessity has not been nearly so great, matters at stake not nearly so vital, as that we, bearing peculiar blunders, suffering under especial hardships, enduring peculiar privations, should meet for a “good talk” among ourselves.

(…) |

Welcome to our first conference. It is important for us, as Black women, to meet to discuss the issues that are important to us. |

| The reasons why we should confer are so apparent that it would seem hardly necessary to enumerate them, and yet there is none of them but demand our serious consideration. In the first place we need to feel the cheer and inspiration of meeting each other; we need to gain the courage and fresh life that comes from the mingling of congenial souls, of those working for the same ends. Next, we need to talk over not only those things which are of vital importance to us as women, but also the things that are of especial interest to us as colored women, the training of our children, openings for our boys and girls, how they can be prepared for occupations and occupations may be found or opened for them, what we especially can do in the moral education of the race with which we are identified, our mental elevation and physical development, the home training it is necessary to give our children in order to prepare them to meet the peculiar conditions in which they shall find themselves, how to make the most of our own, to some extent, limited opportunities, these are some of our own peculiar questions to be discussed.

(…) |

There are so many reasons for us to meet that it is almost impossible to count them. We need to celebrate being here together and discuss the issues that are important to the Black community. |

| I have left the strongest reason for our conferring together until the last. All over America there is to be found a large and growing class of earnest, intelligent, progressive colored women, women who, if not leading full, useful lives, are only waiting for the opportunity to do so, many of them warped and cramped for lack of opportunity, not only to do more but to be more; and yet, if an estimate of the colored women of America is called for, the inevitable reply, glibly given, is, “For the most part ignorant and immoral, some exceptions, of course, but these don’t count.”

(…) |

The most important reason for us to meet is to provide our fellow Black women with opportunities. |

| Our woman’s movement is woman’s movement in that it is led and directed by women for the good of women and men, for the benefit of all humanity, which is more than any one branch or section of it. We want, we ask the active interest of our men, and, too, we are not drawing the color line; we are women, American women, as intensely interested in all that pertains to us as such as all other American women; we are not alienating or withdrawing, we are only coming to the front, willing to join any others in the same work and cordially inviting and welcoming any others to join us. | Although this is a movement of Black women, we want to include people of all genders and races into this conversation. |

“Address of Josephine St. P. Ruffin, President of Conference,” Historical Records of Conventions of 1895-1896 of the Colored Women of America, 1902. University of Chicago.

Background

The years after the Civil War saw a significant increase in the number of social service clubs for women. These clubs, which were led by women, were designed to provide their members with opportunities to engage in community service, charitable work, and reform. Clubs met to discuss issues that were important to them, including education, healthcare, temperance, and voting rights. Members were predominantly wealthy and middle-class women, who had the time and financial ability to engage in this work. The movement started with clubs that were based in local communities. However, by the end of the 19th century, the movement gained so much momentum that national federations of clubs started to form.

Members of women’s clubs were predominantly white, and Black women were typically not allowed to join. Black women also recognized that the needs of the Black community were inherently different from the needs of white women. So Black women formed their own women’s clubs, often focusing on ending racial inequality and providing social services for Black communities. They built on the existing structure of white women’s clubs and adapted the model to their needs.

In 1895, members from Black women’s clubs met in Boston for the First National Conference of Colored Women. A Southern journalist, James Jacks, had slandered Ida B. Wells while she was on an anti-lynching tour in England. Black women felt the need to support her activism, which reflected their own views. There were 53 attendees representing clubs from 14 different states and Washington, D.C. Over three days, women discussed a wide variety of topics including voting rights, motherhood, and literature. On the fourth and final day of the conference, attendees established an official national federation of Black women’s clubs, the National Federation of Afro-American Women (NFAAW). The following year, the NFAAW merged with the National League of Colored Women, forming the National Association of Colored Women.

About the Document

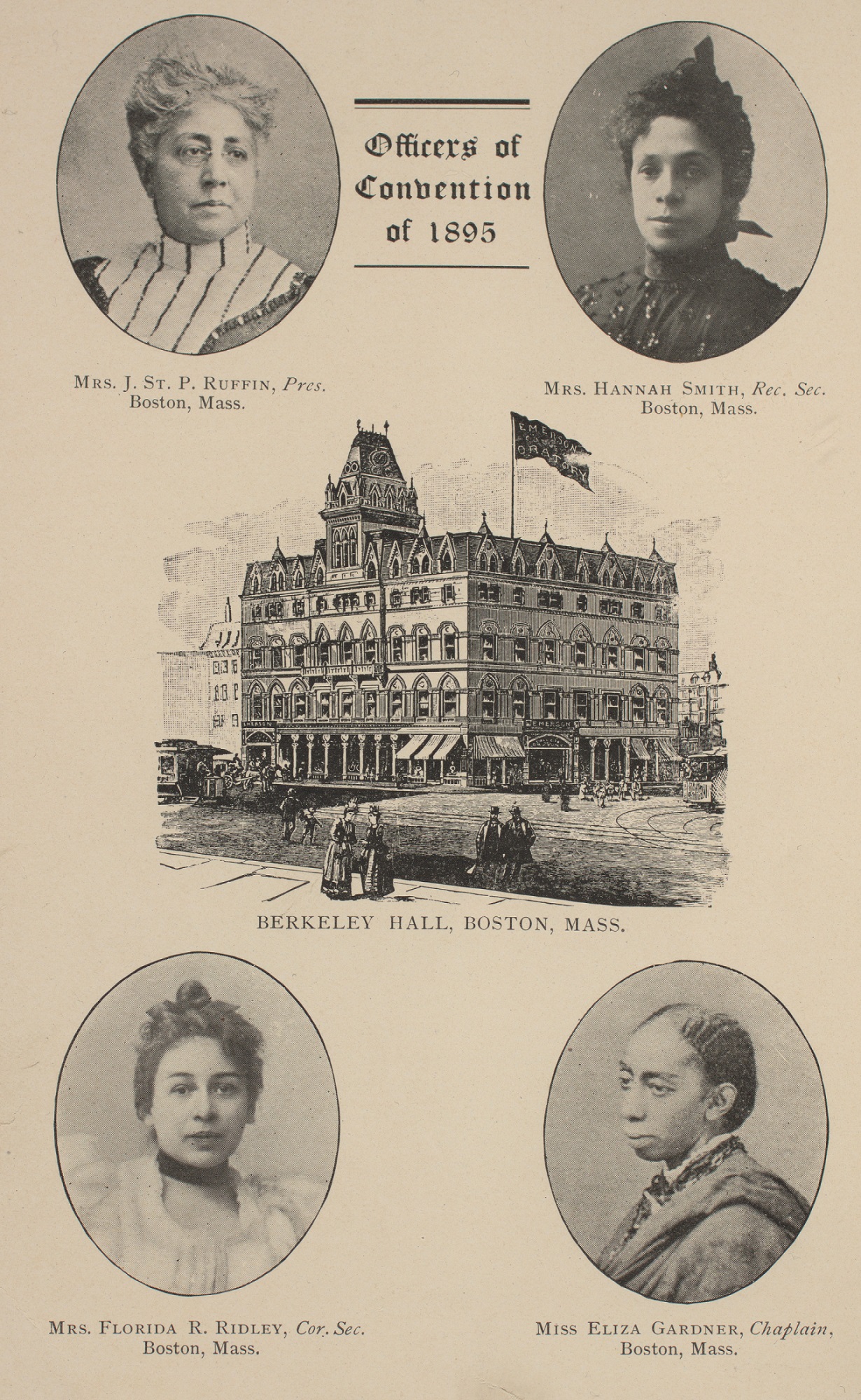

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, the editor of The Woman’s Era, the first publication for Black women, was the president of the conference. The poster depicts her and four other officers: Hannah Smith, Florida Ruffin Ridley, and Eliza Gardner. All four women were members of the Boston Woman’s Era Club, which was organized by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin.

In her welcome speech, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin stated that it was important for Black women to meet as a community. She expressed the hope that the conference would lead to new opportunities for Black women.

Vocabulary

- congenial: Pleasant or agreeable.

- cordially: In a friendly way.

- cramped: Feeling stuck.

- enumerate: To mention several things one by one.

- federations: Larger organizations of smaller, independent groups.

- glibly: In a fluent but insincere way.

- peculiar: Belonging exclusively to something specific.

- privations: Lack of basic human needs.

- progressive: Forward-looking.

- warped: Out of shape or strange.

Discussion Questions

- What were women’s clubs? Why did Black women want to organize their own women’s clubs?

- How does the poster portray the women who organized the conference? What does that indicate about members of Black women’s clubs?

- What goals did Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin express in her welcome speech?

- What challenges for Black women does Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin describe in her speech?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 6.11: Reform in the Gilded Age

- Pair this resource with the life story of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin.

- Read the article by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. What goals did white and Black women share as activists? How did their goals differ?

- Popular topics in discussions for Black women’s clubs were morality and the temperance movement. Combine this resource with the Comstock Act and the temperance movement to consider what morality and womanhood meant for members of Black women’s clubs.

- Explore Black women’s activism during this time period by combining this resource with Ida B. Wells’s article about Jim Crow and the life stories of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Lucy Parsons, and Edmonia Lewis.

- For a larger lesson on the experiences of Black women during this time period, combine this life story with resources about Black domestic workers, convict laborers, a strike at an Atlanta factory, images of Exodusters, Ida B. Wells’s article about Jim Crow, and the life stories of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Edmonia Lewis, Mary Ellen Pleasant, and Lucy Parsons.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE