Mamie Carthan was born in 1921 in Mississippi. When she was two years old, her family moved to the outskirts of Chicago, Illinois. The Great Migration shaped Mamie’s life. In the summer, she visited family back in Mississippi. The rest of the year, her mother’s house was full of newly-arrived family members from the South seeking advice and a better life.

Shortly after graduating near the top of her high-school class, Mamie married Louis Till. Mamie and Louis had one son named Emmett. Louis turned out to be a violent man. When Emmett was just a few months old, Mamie filed a court order against her abusive husband. The judge made Louis choose between jail and the army. Louis chose the army.

In July 1945, Louis died. The army sent Mamie his only personal item: a ring with his initials. Mamie eventually learned that Louis was executed for rape and murder. From then on, she almost never spoke of him. But she saved the ring because she believed Louis would have wanted Emmett to have it.

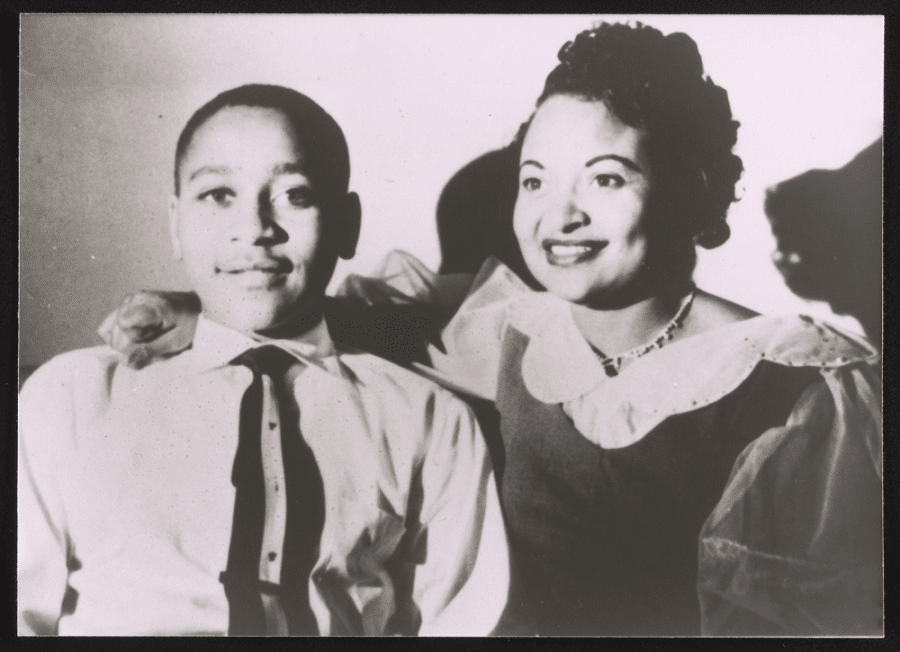

By 1954, Emmett was growing into a responsible teenager. Mamie worked long hours as a secretary, so Emmett cooked and cleaned for his family. That Christmas, Mamie gave Emmett a new suit, and the two posed for a family portrait.

The following summer, Mamie’s Uncle Moses invited Emmett to visit his Mississippi farm for two weeks. Mamie agreed but only after a serious talk. Mississippi was not Chicago. Even though racism existed in both places, the rules for Black people were stricter in the South. Mamie recommended Emmett avoid white people. Fourteen-year-old Emmett understood. He packed his father’s ring so he could show it to his cousins. At the train station, they hugged for such a long time that Emmett almost missed his train.

One week later, Mamie woke up to the phone ringing. It was her cousin. White men with guns had kidnapped Emmett in the middle of the night.

A few days earlier, Emmett and his cousins had visited a store to buy candy. The store was run by a white woman named Carolyn Bryant. While sitting on the porch, Emmett whistled. The whistle was not directed at anyone, but the boys fled before Carolyn could think otherwise. They were too afraid to tell any adults Emmett whistled. By now, Carolyn was claiming young Emmett did more than whistle. According to her, he asked her for a date and grabbed her waist. Emmett’s cousins insisted none of that happened.

Mamie and her family did everything they could to find Emmett. They contacted local newspapers, the NAACP, and even the White House via telegram. On Wednesday, another call came—Emmett’s body was found in a nearby river. He had been shot and beaten almost beyond recognition. His body was weighed down with a large fan and barbed wire. Uncle Moses identified the body. It was difficult to make out any facial features, but he recognized Emmett’s ring.

The local authorities wanted to bury Emmett right away. Mamie called a Black funeral home in Chicago to help. After negotiations that involved a Chicago Congressman, plans were finally made to bring Emmett home. At the funeral home, Mamie insisted she see Emmett’s horribly mangled face and body. The funeral director hesitated. The Mississippi authorities had agreed to send the body only if the casket stayed sealed. Mamie did not care. As she looked at her son, Mamie had one thought: “Let the people see what they did to my boy.” She ordered an open-casket viewing.

Nearly 100,000 people viewed Emmett’s body over four days. It felt like most of Black Chicago paid their respects. So many people could relate to Mamie. They too had come north. They too worried about the safety of their families in the South. They too felt powerless to protect their children.

Mamie granted a photographer from the national Black magazine Jet permission to photograph Emmett’s body and publish the pictures. Although every major newspaper in the country covered Emmett’s funeral, only Jet and a few other Black publications printed photographs of his body. Black Americans came to know those images well. The vast majority of white Americans did not.

Two men were arrested for Emmett’s murder: Carolyn’s husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, J.W. Milan. The fan tied to Emmett’s body came from J.W.’s property. Uncle Moses identified them as the men who came to his house looking for Emmett. But all of this evidence was unlikely to matter to an all-white jury in Mississippi.

I’ve been brokenhearted, but I still maintain an oversized capacity for love.

The public funeral brought extra attention to the trial. Reporters and civil rights activists from across the country descended on the tiny town. At the trial during her testimony, Mamie tried her best to impress the jury. For fear the jury might think she was aggressive, Mamie did not make eye contact with the defendants. She also did not cry because she did not want the jury to perceive her as weak. The defense attorney tried to poke holes in her statements. He suggested she incorrectly identified her son’s body. He criticized her for warning Emmett about Mississippi and suggested Emmett must have been a troublemaker. Mamie stayed calm during the questioning.

On Friday, September 23, 1955, the jury returned a verdict of “not guilty” after just over an hour of deliberations. Mamie was not present for the verdict, which she fully expected to be unjust. She was already on her way out of town and away from any possible retaliation.

Two days later, Mamie was on a stage before 10,000 people in Harlem. Civil rights leader A. Phillip Randolph organized the protest and spoke passionately about the injustice of the verdict. But Mamie’s moving speech was the highlight.

Mamie agreed to go on tour with the NAACP, which organized a series of events around Emmett’s story. In October, Mamie visited 33 cities in 19 states. She told the crowds she was no longer sad. She was “just plain angry.” Emmett’s death was going to wake up Black America to fight for change.

By the end of the month-long tour, Mamie was exhausted. The NAACP arranged for a second tour. Mamie asked if her father could join for moral support and if she could be paid more since she could not work and travel at the same time. The Executive Director of the NAACP was furious. He accused her of taking advantage of the situation. Mamie later sent a letter apologizing for any offense. She was not an activist but a mother wanting to help the cause. She said she would handle her own financial concerns. Mamie was ready to go. But, still, the NAACP said no.

Even though her speaking tour was cancelled, Mamie’s actions had already contributed to the growing civil rights movement. People of all races were outraged. Government officials across the country received angry letters demanding justice. In the years to come, people like Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lewis pointed to Emmett Till’s funeral as a turning point in the fight for racial justice in America.

Telling Emmett’s story helped Mamie process the tragedy. In 1956, she enrolled at Chicago Teachers College. The following year, she married her boyfriend, Gene Mobley. She graduated in 1960 and worked as a teacher until her retirement in 1983.

In the late 1980s, Emmett’s story was part of a major PBS documentary. For the first time, white America saw the images of Emmett’s battered body that Black America saw decades earlier. The public wanted to hear from Mamie. She contributed as much as she could. Mamie still believed her mission was to tell Emmett’s story.

Mamie Till-Mobley died of cancer in 2003. Her memoir was published the same year. In it, she admitted that she thought about Emmett every moment of every day.

Vocabulary

- casket: A coffin or box containing a dead person’s body.

- testify: To answer questions or give evidence in a court case.

- defendant: A person accused of something in a court case.

- lynching: The illegal execution of a person by a mob or group.

- migration: Movement from one place to another.

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): A civil rights organization that was founded in 1909 to oppose discrimination and still exists today.

Discussion Questions

- How did the Great Migration and family play a role in Mamie’s life?

- Why was Mamie concerned about Emmett traveling to Mississippi?

- What actions did Mamie take from the moment she learned about Emmett’s disappearance through the court case? What do these actions tell you about Mamie’s character?

- What do you learn about Emmett’s murder trial from this life story? What does this tell you about the legal system in Mississippi at the time of his death?

- How did Emmett’s death shape Black and white Americans’ lives differently? How did people learn about his story and when? Why is this significant? What does it tell you about history and memory in society?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connections:

- 8.2: Cold War from 1945-1980

- 8.6: Early Steps in the Civil Rights Movement (1940s & 1950s)

- The Great Migration played a significant role in Mamie Till-Mobley’s life. Learn more about family and motherhood in the Great Migration by pairing this life story with these Great Migration photographs, as well as other related resources in WAMS.

- Emmett Till was a victim of lynching. Learn more about this horrifying part of American history in the Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow curriculum guide.

- By holding an open casket funeral, Mamie took a stance against lynching in America. Compare her life story with that of another famous Black Chicagoan and anti-lynching crusader, Ida B. Wells.

- Women played a critical role in the African American struggle for civil rights in this era. Combine this document with other resources about women in the Civil Rights Movement, including the life stories of Ella Baker, Pauli Murray, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mary Church Terrell, and Dorothy Bolden, in addition to the resources on the Little Rock Nine, Loving v. Virginia, and Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony about voting rights.

- If you feel it is appropriate for your students, show them a photograph of Mamie with Emmet’s body, which is available here. (PLEASE NOTE: This link will take you directly to deeply disturbing and graphic content.) Ask students to discuss how their understanding of Mamie’s story changed or deepened after seeing this painful photograph.

- Most white Americans did not see Emmett Till’s body until the documentary Eyes on the Prize aired on national television in 1987. If you feel it is appropriate, show the section on Emmett Till part (Episode One, minutes 10:26-24:30, available for free through Facing History and Ourselves) and ask students to consider why this documentary was important and how Black Americans might have reacted to the shock white Americans faced over 30 years after Jet magazine published the same images. (PLEASE NOTE: The suggested clip includes graphic and disturbing images and potentially triggering information. We recommend viewing the entire clip before determining whether it is appropriate for your students.)

- In 2016, the Smithsonian’s National Museum for African American History and Culture opened with a permanent display space for Emmett’s casket. It was the first time the casket was displayed since Emmett’s funeral in 1955. Invite students to research this topic. How did the museum acquire the casket? Why did they want to put it on view? What does this tell students about the importance of history and commemoration? How does Mamie’s life factor into all of this.

- Mamie is just one of countless Black mothers who have lost their children to lynching and racial violence in the United States. Invite students to research other mothers who have faced similar tragedies, including Valerie Bell (mother of Sean Bell), Sybrina Fulton (mother of Trayvon Martin), Gwen Carr (mother of Eric Garner), Tanika Palmer (mother of Breonna Taylor), and many more.

- Mamie’s life speaks to the particular challenge Black mothers face in raising children under the threat of racial violence and white supremacy. Explore the lived experience of Black mothers in the 20th century by connecting Mamie’s life story to a photograph of the Atlanta Neighborhood Union, an article about Black suffrage that discusses juvenile justice reform, and the Panther Sister document that includes an image of a militant Black mother.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE