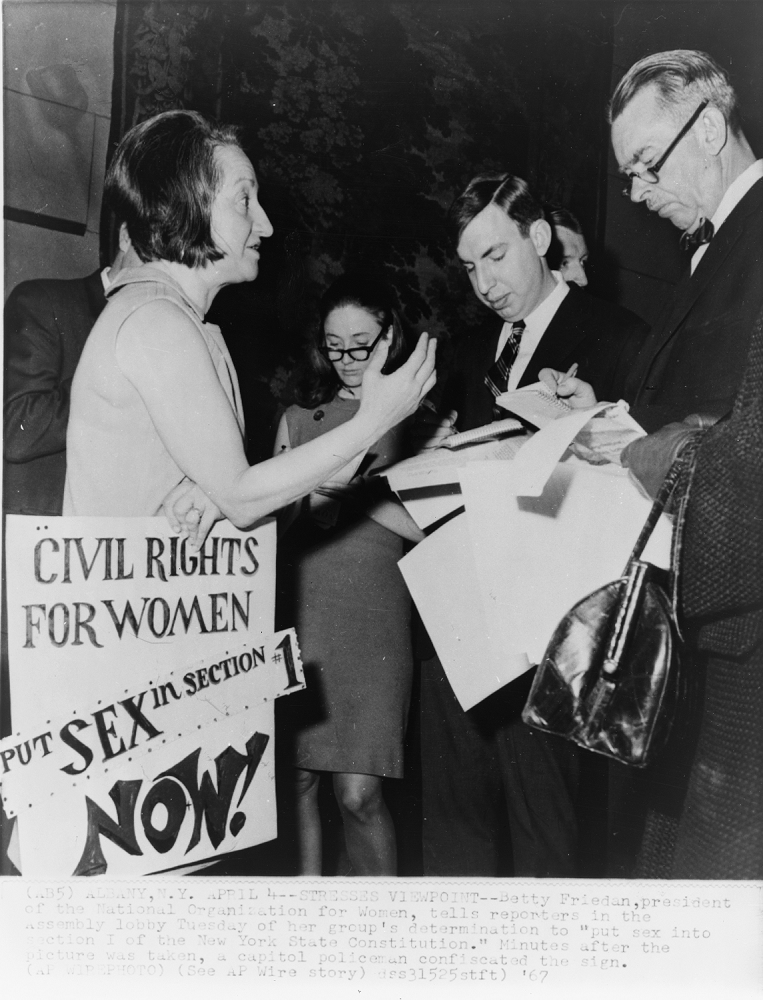

Betty Friedan, president of the National Organization for Women

Betty Friedan, president of the National Organization for Women, tells reporters in the New York State Assembly lobby of the groups intention to “put sex into section I of the New York constitution”, April 4, 1967. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., NYWT&S Collection, LC-USZ62-122632.

Bettye Goldstein was born on February 4, 1921, in Peoria, Illinois. Her father was a Russian immigrant who ran his own store. Her mother was a newspaper editor who gave up her career to raise three children and later acknowledged she missed working.

Bettye studied psychology at Smith College, a prestigious women’s school. As a senior, she served as the editor of Smith’s student newspaper. Under Bettye’s leadership, the newspaper took on more political topics. The articles explored America’s role in World War II, the threat of fascism, and the importance of unions. Many of Bettye’s classmates and teachers worried the paper was too radical. Bettye disagreed and saw these conversations as important to democracy. In 1942, she graduated with honors from Smith College.

The following year, Bettye accepted a research fellowship in psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. She also decided to drop the second “e” in her name. From then on, she was Betty, not Bettye.

After a year of research, Betty moved to New York City to work as a reporter for several labor union publications. Betty’s articles covered a range of issues. She was interested in the connections between labor organizing and communism, the unfair treatment of Jews and African Americans in the workplace, and the unique challenges women faced at work.

In 1947, Betty married Carl Friedan. At first, Betty continued to work while raising their first child. However, when her second child was born in 1953, her employer refused to let her take a second maternity leave. Betty was forced to leave her job. After that, she occasionally wrote articles for women’s magazines, but her career as a union journalist was over. She and Carl had a third child and moved from New York City to the suburbs.

Betty started to feel depressed. She loved her children and husband, but she questioned her purpose. She had been a star student at Smith, but she barely used her education as a housewife. Even writing a few articles for women’s magazines was unrewarding. She felt guilty about spending even a small amount of time on paid work. Something inside her said that her husband and children should come first.

Betty started to research the psychology behind these feelings and wondered if other women felt the same. In 1957, she sent out a survey to nearly 200 fellow Smith graduates. The survey included over 35 questions about the participants’ lives. Many of them focused on marriage and motherhood: Is your marriage satisfying? Do you enjoy being with your husband more than anyone else? Does your husband complain about your housework? Do you worry about money? Do you have a career ambition? If your main occupation is homemaker, do you find it totally fulfilling?

Betty was both relieved and disappointed with the responses. The good news was she was not alone. The bad news was that many married women reported feeling unfulfilled, depressed, and that they were unequal partners in their marriage. Betty repeated the survey with more graduates of women’s colleges and recognized a trend.

By 1963, she compiled her findings in a book, The Feminine Mystique. In it, she attacked what she saw as the myth of domestic happiness. She blamed educators, psychologists, advertisers, and the media for convincing women that their ultimate purpose was marriage and motherhood. She also believed that society taught women to think there was something wrong with them if they wanted a career or personal life outside the home. She described the deep depression many middle-class women felt as housewives. She complained about the way society encouraged women to see college not as a step toward a career but as a step toward finding a husband.

Betty concluded that this situation hurt all of American society. The unhappiness these women felt hurt their marriages and their children. Also, the women’s unwillingness or inability to contribute to the growing workforce outside the home hurt the economy. And their inactivity in the political realm prevented full gender equality.

It was . . . a sense of dissatisfaction. . . . As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children . . . she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—Is this all?

The Feminine Mystique was an immediate success, and Betty was an instant celebrity. Women and men across the country read and discussed it. For many suburban housewives, the book served as a wake-up call and reminder that they were not alone. For many middle-class women who were not housewives, it was confirmation that they were not failures. For an even broader audience, the book brought attention to the dangers of treating women as second-class citizens in any environment—suburban or not.

Betty’s instant fame came at a cost. Many of her friends uninvited her and her children to dinner parties and playdates. Betty and Carl divorced a few years later.

Betty knew that writing about the inequality women faced was only the first step. In 1966, she attended a government-sponsored conference about women. Like many of the attendees, she was frustrated by the event. The government refused to acknowledge the participants’ demands, which included equal employment opportunities for men and women.

Betty invited nearly 20 conference attendees to meet in her hotel room. As the night wore on, everyone was in agreement. Women needed an organization that would fight on their behalf. By the next day, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was formed. A few months later, 300 men and women signed on as NOW’s first members. They elected Betty as their president.

NOW fought for protections against job discrimination, improved child care, free and legal abortions, and the passage of an Equal Rights Amendment. In 1970, NOW organized the Women’s Strike for Equality. Women across the country and the world participated in marches, conferences, and events to honor the 50th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment. In New York City, Betty led a march of over 10,000 women representing a wide range of feminist organizations.

But Betty’s relationship with the growing feminist movement was becoming increasingly problematic. Her research and writing continued to focus on white, middle-class, and college-educated women. She often spoke as if all women had the same needs. She rarely acknowledged or discussed the different needs and experiences of women of color, women from lower income levels, and LGBTQ women.

Betty also believed younger, more radical activists were jeopardizing the women’s movement. She wanted to keep the focus on issues of employment and child care. She was particularly concerned about the role of lesbians, whom she described as a “lavender menace.” She believed lesbians hated men and placed too much emphasis on sex. As NOW embraced a diverse membership and welcomed lesbian members, Betty stepped down as president.

Betty’s ideas about women’s equality were transformative but limited. In the 1970s and 1980s, she continued to write and teach at universities around the country. She also held leadership roles within many important initiatives, including the National Women’s Political Caucus and the National Conference on Women’s Rights. However, she was seen as part of an older generation. People described her as a mother of the movement and not necessarily as its leader.

Betty died of cardiac arrest in 2006 on her 85th birthday. The Feminine Mystique is still considered one of the most important texts of the American feminist movement. Over three million copies have been sold in dozens of languages around the world.

Vocabulary

- abortion: A procedure to end a pregnancy.

- communism: A political system in which all goods and items of value are collectively owned and distributed to citizens equally.

- Equal Rights Amendment (ERA): A proposed amendment to the United States Constitution stating that rights may not be denied on the basis of a person’s sex.

- fascism: A political system that values the rights of the nation over the rights of individual citizens and is often led by a powerful and popular leader or dictator. Fascism often includes deciding who belongs in a nation by using racial or ethnic categories.

- feminine: Associated with being a woman.

- feminism: The belief that men and women are equal.

- mystique: A special or mysterious state of being.

- radical: Extreme.

Discussion Questions

- How do you think Betty’s early life shaped her later work as an author and feminist activist?

- Many scholars debate whether Betty actually fits the stereotype she wrote about. Based on what you have read, what do you think? To what extent was she the typical housewife? To what extent was she not?

- Betty was and is still criticized for focusing on middle-class suburban women in The Feminine Mystique and overlooking women of color, LGBTQ women, and working-class women. What do you think about this criticism?

- Despite its narrow focus, many scholars agree that The Feminine Mystique had a huge impact on popular culture, feminist activism, and American history. Why do you think her book mattered so much?

- How did Betty involve herself in the growing feminist movement after the publication of The Feminine Mystique? Where did she agree as well as disagree with other activists?

- Why did Betty step away from a leadership role in NOW in 1970? What does this tell you about her personality and beliefs and life in the United States at this time?

- Betty often excluded other women through her words and actions. What do you think about this? Do you think her story should still be told? Why or why not?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 8.11: The Civil Rights Movement Expands

- Invite students to conduct a close analysis of the two photos connected to this life story, as well as a photograph of Betty’s participation in the 1977 Conference on Women’s Rights. What details do they notice in each image? What do students learn about Betty’s life in each?

- Betty was one of the organizers of the Women’s March for Equality in 1970. Examine materials from that march and connect them to Betty’s life story. How did her work contribute to this growing movement? How did her personal opinions conflict with the various groups represented in these photographs?

- Betty was part of a powerful network of feminist activists in the 1960s and 1970s. Connect her to many of her colleagues by reading this life story in conjunction with the life stories of Bella Abzug and Pauli Murray, the interview with Shirley Chisholm, and the article by Gloria Steinem.

- The Feminine Mystique and Betty’s subsequent activism was a direct critique of suburban life. Invite students to study the photographs of Glasgow Village, the film of the suburban shopping mall, the photographs of kitchen appliances, and the transcript of the Kitchen Debates to understand the ideal Betty rejected.

Themes

AMERICAN CULTURE; ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY