Anita Hill’s testimony

Thomas Second Hearing Day 1, Part 2. October 11, 1991. C-Span Archives.

Video Transcript |

| SENATOR BIDEN: Professor, do you swear the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so help you God?

PROFESSOR HILL: I do. SENATOR BIDEN: Thank you. Professor Hill, please make whatever statement you wish to make to the committee. PROFESSOR HILL: Mr. Chairman, Senator Thurmond, members of the committee. My name is Anita F. Hill, and I am a professor of law at the University of Oklahoma. I was born on a farm in Okmulgee County, Oklahoma, in 1956. I am the youngest of 13 children. I had my early education in Okmulgee County. My father, Albert Hill, is a farmer in that area. My mother’s name is Irma Hill. She is also a farmer and a housewife. My childhood was one of a lot of hard work and not much money, but it was one of solid family affection, as represented by my parents. I was reared in a religious atmosphere in the Baptist faith, and I have been a member of the Antioch Baptist Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma, since 1983. (…) I graduated from the university with academic honors and proceeded to the Yale Law School, where I received my JD degree in 1980. (…) During this period at the Department of Education, my working relationship with Judge Thomas was positive. I had a good deal of responsibility and independence. I thought he respected my work and that he trusted my judgment. After approximately three months of working there, he asked me to go out socially with him. What happened next and telling the world about it are the two most difficult things — experiences of my life. It is only after a great deal of agonizing consideration and sleepless number — a great number of sleepless nights — that I am able to talk of these unpleasant matters to anyone but my close friends. I declined the invitation to go out socially with him and explained to him that I thought it would jeopardize at what at the time I considered to be a very good working relationship. I had a normal social life with other men outside of the office. I believed then, as now, that having a social relationship with a person who was supervising my work would be ill-advised. I was very uncomfortable with the idea and told him so. I thought that by saying no and explaining my reasons my employer would abandon his social suggestions. However, to my regret, in the following few weeks, he continued to ask me out on several occasions. He pressed me to justify my reasons for saying no to him. These incidents took place in his office or mine. They were in the form of private conversations which not, would not have been overheard by anyone else. My working relationship became even more strained when Judge Thomas began to use work situations to discuss sex. On these occasions, he would call me into his office for reports on education issues and projects, or he might suggest that, because of the time pressures of his schedule, we go to lunch to a government cafeteria. After a brief discussion of work, he would turn the conversation to a discussion of sexual matters. His conversations were very vivid. (…) On several occasions, Thomas told me graphically of his own sexual prowess. Because I was extremely uncomfortable talking about sex with him at all, and particularly in such a graphic way, I told him that I did not want to talk about these subjects. I would also try to change the subject to education matters or to nonsexual personal matters such as his background or his beliefs. My efforts to change the subject were rarely successful. Throughout the period of these conversations, he also, from time to time, asked me for social engagements. My reaction to these conversations was to avoid them by eliminating opportunities for us to engage in extended conversations. This was difficult because at the time I was his only assistant at the Office of Education — or Office for Civil Rights. During the latter part of my time at the Department of Education, the social pressures and any conversation of his offensive behavior ended. I began both to believe and hope that our working relationship could be a proper, cordial, and professional one. When Judge Thomas was made chair of the EEOC, I needed to face the question of whether to go with him. I was asked to do so, and I did. The work itself was interesting, and at that time it appeared that the sexual overtures which had so troubled me had ended. I also faced the realistic fact that I had no alternative job. While I might have gone back to private practice, perhaps in my old firm or at another, I was dedicated to civil rights work, and my first choice was to be in that field. Moreover, the Department of Education itself was a dubious venture. President Reagan was seeking to abolish the entire department. For my first months at the EEOC, where I continued to be an assistant to Judge Thomas, there were no sexual conversations or overtures. However, during the fall and winter of 1982, these began again. The comments were random and ranged from pressing me about why I didn’t go out with him to remarks about my personal appearance. I remember his saying that some day I would have to tell him the real reason that I wouldn’t go out with him. He began to show displeasure in his tone and voice and his demeanor and his continued pressure for an explanation. He commented on what I was wearing in terms of whether it made me more or less sexually attractive. The incidents occurred in his inner office at the EEOC. |

Background

President George H.W. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court in 1991. Shortly after the announcement, rumors spread that he might have engaged in sexual harassment against one of his employees, Anita Hill, while he was the chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). He made comments about sex and repeatedly asked her out, even after she refused his advances.

The EEOC was established through the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to investigate accusations of discrimination in the workplace. Based on the growing number of women reporting incidents of sex discrimination, the EEOC established new guidelines regarding sexual harassment in 1980. The guidelines challenged the idea that sexually explicit jokes and pornographic materials were acceptable forms of flirting. In the case Meritor Savings v. Vinson from 1986, the Supreme Court ruled that sexual harassment was a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Ironically, this was the exact type of behavior Anita Hill was hesitant to report as an employee of the EEOC.

Anita Hill was reluctant to participate in the hearings. The Senate Judiciary Committee subpoenaed her to testify.

About the Document

The video is an excerpt of Anita Hill testifying in the confirmation hearings for Clarence Thomas. She was a law professor at the University of Oklahoma at the time. The Judiciary Committee, chaired by then-Senator Joe Biden, consisted of only white men. There were only two female senators in 1991. The senators questioned Anita Hill’s integrity and asked her personal questions, even asking her if she was a “scorned woman.” Conservative senators were particularly harsh, as they were determined to have the deeply conservative judge confirmed to the nation’s highest court. Clarence Thomas defended himself by claiming Anita Hill’s testimony was an example of racism against Black men. The Senate confirmed his nomination to the Supreme Court, where he is seated until this day.

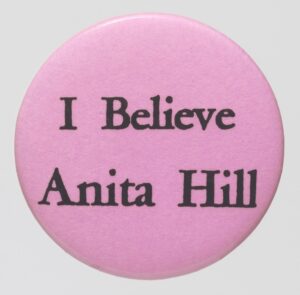

The pin-back button was worn to show support for Anita Hill. 86 percent of Americans watched at least part of the hearings and six in ten Americans supported Anita Hill. Her testimony led to discussions of sexual harassment and the treatment women received in the workplace. Many women recognized that they had encountered the behavior Anita Hill described themselves. After a conservative backlash against feminism had generated momentum throughout the 1980s, the confirmation hearings inspired renewed support for the feminist movement.

Vocabulary

- Judiciary Committee: Committee of senators that oversees the Department of Justice. One of their responsibilities is to conduct hearings for nominated judges and justices.

- sexual harassment: The behavior of repeated and unwelcome sexual comments and behavior in the workplace. The Supreme Court established two dimensions of sexual harassment: quid pro quo (direct) and hostile work environment.

- subpoena: To legally require someone to testify in a legal proceeding.

Discussion Questions

- Why does Anita Hill focus on her religion and family background at the start of her testimony? Why does she apologize for describing Clarence Thomas’ behavior?

- How do you think her identity as a Black woman affected her perception by the Senators in the room? How did it affect the average American viewer?

- How did Anita Hill’s testimony inspire other women to challenge the sexual harassment they experienced in the workplace?

- What does her testimony say about how victims of sexual harassment are judged by the public? Do you think this has changed since 1991?

Suggested Activities

- AP Government Connection: 2.11: Checks on the Judicial branch

- Compare the testimony of Anita Hill in 1991 to the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford in the confirmation hearings for Brett Kavanaugh in 2018. How were both women treated by the senators and the public? What impacts might the #MeToo movement have had?

- When Anita Hill testified, there were only two female senators. Pair this resource with images of newly elected female senators the following year to consider the impact her testimony had on American politics.

- Consider the challenges professional women faced in the workplace by combining this resource with images of power suits.

- For a larger lesson on the contributions of Black women during this period, combine this resource with the first female hip hop MC, feminist zines and music, and the life stories of Audre Lorde, Lois Curtis, Barbara Lee, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy.

- Consider the role of women in politics during this period by combining this resource with Maxine Waters speaking on the Rodney King verdict, a testimony about music censorship, the Year of the Woman, Geraldine Ferraro’s acceptance speech, Hillary Clinton’s speech, and the life stories of Sandra Day O’Connor and Barbara Lee.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; POWER AND POLITICS