Home / Early Encounters, 1492-1734 / Dutch Colonies / Life Story: Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1715)

Resource

Life Story: Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1715)

Scientist and Adventurer

The story of the first woman to make a journey to the Americas for scientific purposes.

- About

-

Curriculum

- Introduction

-

Units

- 1492–1734Early Encounters

- 1692-1783Settler Colonialism and the Revolution

- 1783-1828Building a New Nation

- 1828-1869Expansions and Inequalities

- 1832-1877A Nation Divided

- 1866-1898Industry and Empire

- 1889-1920Modernizing America

- 1920–1948Confidence and Crises

- 1948-1977Growth and Turmoil

- 1977-2001End of the Twentieth Century

- Discover

-

Search

Maria Sibylla Merian was born in 1647 in Frankfurt am Main, a city in what is now Germany. She was raised in a family of famous publishers and artists that had connections all over Europe.

Maria Sibylla enjoyed a very privileged childhood. Along with the traditional girl’s education of reading, writing, and household tasks, she learned painting and printmaking alongside her brothers. But when her brothers were allowed to travel around Europe to finish their artistic education, Maria Sibylla was held back because girls of her social standing were not allowed that kind of freedom.

Instead, Maria Sibylla found inspiration in her own backyard. At the age of thirteen, she began to collect and study insects. She was fascinated by the metamorphosis, or change, that insects undergo over the course of their lives. Her first serious study was a collection of drawings and descriptions of the life cycle of silkworms. She was able to acquire many silkworm samples because her uncle was a silk manufacturer. Her family was a bit confused by her love of insects, but they were impressed by her artwork and encouraged her studies.

In 1665, when Maria Sibylla was eighteen years old, she married her stepfather’s apprentice, John Andreas Graff. Three years later, she gave birth to their first daughter, Johanna. In 1670 the small family moved to John’s hometown, the city of Nuremberg. Maria Sibylla’s reputation as an artist spread quickly in her new city, and she started teaching other young women how to paint and draw. She also studied the plant and insect life of Nuremberg, and continued to create her art. In 1675 her husband published Maria Sibylla’s first book, a collection of flower and plant illustrations intended to be used as models and patterns for works of art and embroidery. A woman publishing a book was a major accomplishment, but Maria Sibylla was already hard at work preparing something much more ambitious.

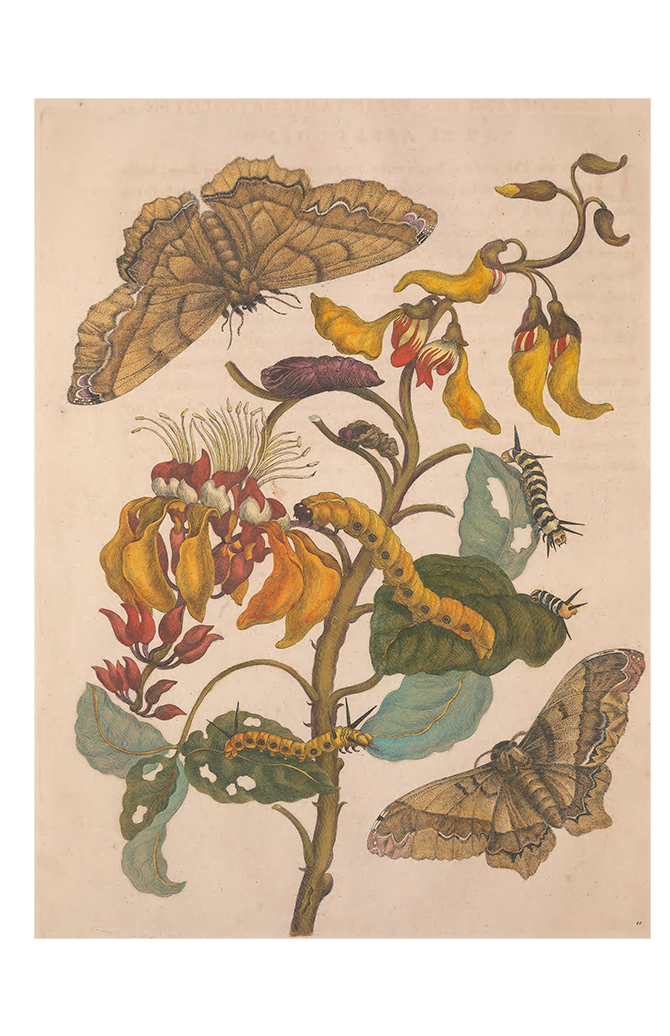

In 1679, just a year after the birth of her second daughter Dorothea, Maria Sibylla published her first scientific book, The Wonderful Transformation and Singular Flower Food of Caterpillars … Painted from Life and Engraved in Copper. In each illustration, Maria Sibylla painted the entire life cycle of her subject: from egg to larva (caterpillar) to pupa (chrysalis) to butterfly or moth. She painted all of these different stages around the plant that was the subject’s main source of food and wrote short texts describing her observations. This was not just a book of illustrations, but a book intended to share what she had learned with others. Her work impressed the scientific community and established Maria Sibylla as an important new voice in the growing field of entomology, the study of insects.

Maria Sibylla is remembered today as one of the most important woman scientists of the Enlightenment.

In 1685 Maria Sibylla left her husband and took her daughters to join a radical Christian community. Her husband chose to divorce her rather than join them. Maria Sibylla and her daughters lived with the community for six years, but eventually she grew frustrated that the community did not value education and scientific exploration. She moved to Amsterdam and began the process of building a new life.

Amsterdam in the 1690s was one of the intellectual capitals of Europe, and Maria Sibylla quickly re-established herself as an important artist and entomologist. She made money to support her family by teaching and selling her works of art. When her eldest daughter married a merchant, she used his trade connections to collect insect specimens from the Americas. Eventually, Maria Sibylla grew tired of studying the long-dead specimens that were available in Amsterdam. She wanted to observe the entire life cycle of her subjects, to understand how they interacted with the world around them. In 1699 she sold her entire stock of art and specimens and used the funds to buy passage to the Dutch colony of Suriname on the northeast coast of South America. This decision was remarkable for two reasons: it was unheard of for a woman to take such a journey without the support of a male family member, and it was unprecedented for a scientist to fund their own excursion.

In Suriname, Maria Sibylla and her youngest daughter took daily trips into the nearby jungle to observe and collect insect specimens for study. News of her work spread quickly, and the enslaved Indigenous people in the city began to bring her interesting plants and insects and to share with her what they knew about them. Maria Sibylla later said she learned more from the Indigenous people than she ever learned from the white colonists.

After two years in Suriname, Maria Sibylla returned to Amsterdam, where she began work on a new book about her findings. For the next four years, she wrote in her spare time and worked hard as a teacher and specimen dealer to make the money to publish her book. In 1705 Maria Sibylla self-published her most important work, The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam. Her book allowed European scientists to learn about an entirely different ecosystem without having to travel across the Atlantic Ocean, and it solidified Maria Sibylla’s status as one of the most important scientists in Amsterdam.

For the rest of Maria Sibylla’s life, people came from all over Europe to buy her art and learn her techniques. When she passed away in 1715, her daughters took up her work and continued her legacy. She is remembered today as one of the most important scientists of the Enlightenment.

Vocabulary

- Amsterdam: The capital of the Netherlands.

- apprentice: A person who learns a trade from a more skilled employer.

- Christian: A person who believes in and follows the teachings of Jesus Christ.

- embroidery: The art of decorating fabric with designs created with a needle and thread.

- Enlightenment: A European intellectual movement of the 1600s and 1700s.

- entomology: The scientific study of insects.

- metamorphosis: The change from immature to adult form that many insects and animals undergo. For example, the change from a caterpillar to a butterfly.

- privileged: Having many advantages.

- specimen: An example of a plant, animal, or insect collected for scientific study.

- Suriname: A Dutch colony on the Northeast coast of South America. Also spelled “Surinam.”

Discussion Questions

- How did Maria Sibylla Merian’s education differ from that of her brothers? Why was it different?

- What made Maria Sibylla Merian unique among her peers in the scientific community?

- What life circumstances allowed Maria Sibylla Merian to follow her own path?

- Why is Maria Sibylla Merian’s story important to the history of the Enlightenment?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connections:

- 2.5 Interactions between Native Americans and Europeans

- 2.7 Colonial Society and Culture

- Include this life story in a lesson about the Enlightenment to show students that female scientists made important contributions to science during this era.

- Trace Maria Sibylla Merian’s life journey on a world map to demonstrate the worldwide mobility available to a Dutch person of means in the 1600s.

- Maria Sibylla Merian’s scientific colleagues would have studied her artwork closely for clues about the ecology of the New World. Invite your students to do the same. They can cut up and lay out the different stages of the life cycle of the moth provided as an illustration for the life story and examine the image of the plant for evidence of the ways the moth interacts with it. Then invite students to write a scientific description of the specimen.

- After reading the life story together, conduct a close reading of the portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian. Look specifically for clues the artist left to tell her life story.

- Combine this life story with the following for a lesson on the role of women and innovation in the colonial era:

- Maria Sibylla Merian was one of many women in Europe and the Americas who made important contributions to the Enlightenment. Combine her story with the resources below for a lesson about women and the Enlightenment in the New World:

- Create a lesson about the contributions of female scientists across different eras. Combine this life story with the following:

- Explore the life and work of Maria Sibylla Merian through the creation of watercolor illustrations based on students’ field sketches of local flora and fauna. Students will experience the process of sketching from life and then translating their observations into a painting with elements that make a strong composition.

Themes

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND MEDICINE