Eleanor Roosevelt was born on October 11, 1884 in New York City. She was the oldest of her parents’ three children. Her father, Elliott Roosevelt, was the younger brother of President Theodore Roosevelt. Her mother, Anna Hall Roosevelt, was a descendent of a wealthy New York family who expected her children to live up to upper-class society’s high standards. She often criticized her shy and socially awkward daughter for not being more outgoing and naturally beautiful.

By the age of 10, both of Eleanor’s parents had died. Anna died of diphtheria in 1892. Elliott died of health complications related to drug and alcohol addiction less than two years later. Eleanor lived with her grandmother.

Eleanor received the best possible education. When she was 15 years old, she moved to England to attend the Allenswood School. There, her teachers noticed that the reserved Eleanor was highly intelligent. They encouraged her to use her mind and ignore criticisms like those she had received from her mother.

By the time Eleanor returned to New York three years later, she was a more confident young woman. Although she agreed to participate in balls, teas, and other events expected of young women in high society, she also dedicated time to helping the wider New York City community. She volunteered with the Junior League and the Rivington Street Settlement House. While many members of elite New York donated money to charity, Eleanor felt it was important to donate time and energy. She wanted to meet the people she was helping and offer her knowledge and skills.

Eleanor married her fifth cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, on March 17, 1905. Eleanor’s uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt, walked her down the aisle. Eleanor felt she fulfilled her duty as a young lady through the marriage. Franklin was a promising young political figure and member of the New York elite.

The next decade of Eleanor’s life was primarily focused on married life. She had six children, took care of the house, and supported her husband’s career. Her commitment to family was so strong and her domestic duties so intense that she put her volunteer and activism work aside.

In 1918, Eleanor was heartbroken when she discovered that Franklin had an affair with her social secretary, Lucy Mercer. Eleanor confronted Franklin, but once again fulfilled her social duty by agreeing to stay married to him. Although they remained together, their relationship changed. They supported one another, but did not have the same emotional connection.

Franklin’s betrayal, along with volunteer experiences during World War I, motivated Eleanor to re-prioritize her life. She found time to return to her personal passions. She developed a close circle of friends and advisors equally interested in social reform. Together, they raised awareness on issues of child labor, tenement conditions, education reform, and civil rights.

In the summer of 1921, Franklin contracted polio. Although he survived, he was paralyzed in his legs and required use of a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Franklin thought his political career was over, but Eleanor refused to allow him to give up. She encouraged him to continue working and used her own growing political network to bolster his career.

By the end of the 1920s, Eleanor believed not only that women needed to regularly vote, but also that they needed to involve themselves in politics and social reform. According to her, women had a duty to fight for their own rights. They could not assume equal rights would be offered to them by men in power. Women needed to be leaders.

In 1928, Franklin was elected governor of New York. Just four years later, in 1932, he was elected president of the United States. Eleanor was reluctant about her new role as first lady. She did not want to live a public life, nor did she want to sacrifice her role as an activist. But soon Eleanor realized that she could use her role to make a difference. The nation was suffering under the Great Depression and her husband had a tremendous task ahead of him. Eleanor had been a vital support to Franklin earlier in his career, and she could do it again as first lady.

Franklin’s schedule and physical disability limited his traveling. But Eleanor had few formal obligations and no major physical impediments. This allowed her to become Franklin’s eyes and ears beyond the White House. She traveled across the country, meeting with men, women, and children in need. She visited factories, tenements, mines, and agricultural fields. She provided a smile and a message of encouragement to those who hoped for change.

Although Eleanor was eager to work and serve her country, holding such a high-profile position did not come easily to her. Her relationship with Franklin was more professional than personal, so Eleanor sought support from others. In the 1930s, one of her closest relationships was with newspaper reporter Lorena Alice Hickok, who was often called “Hick.” Eleanor and Hick were close companions who confided in one another through long, personal letters. Hick encouraged Eleanor to hold regular press conferences and to start a weekly column called My Day. Although it is impossible to know how they interacted in private, many historians agree that their letters strongly suggest a romantic relationship. Regardless, Hick played a critical role in Eleanor’s transition from private citizen to national public advocate.

Through My Day and other columns, Eleanor shared what she experienced with a wider audience. She encouraged Americans to write to her. She received hundreds of thousands of letters, and she did her best to respond to as many as possible.

Constituents were smart to seek Eleanor’s attention because she had the president’s ear. Eleanor knew Franklin longer than almost any of his advisors. As his wife, she could say things to him that others could not. She told him what she saw while traveling and what she read in letters she received. She talked to him about her work as a grassroots activist and settlement worker. Her ideas had significant influence on his New Deal policies.

Eleanor was an advocate for women in government. She reminded Franklin that women were capable of incredible social reform, and encouraged him to hire women from across the country to work in the federal government.

The basis of success in a Democracy is really laid down by the people. It will progress only as their own personal development goes forward.

The role of first lady brought Eleanor in contact with people who had not been part of her world as New York socialite and housewife. Eleanor quickly became an advocate for the African American community. She supported the formation of an informal Black cabinet and recruited Black activists (and friends) like Mary McLeod Bethune for high-ranking positions within the federal government. She traveled across the country and attended civil rights conventions. In 1939, she famously canceled her membership to the Daughters of American Revolution (DAR) after the DAR refused to allow African American opera singer Marian Anderson to perform in their theater because of her race. Although she was not always able to bring about change, Eleanor gained the respect of civil rights leaders through her intelligence and willingness to listen.

Eleanor’s commitment to the public and to human rights continued during World War II. Even before the United States entered the war, she spoke out against fascism and brought attention to the plight of Jewish people in Europe. She opposed the internment of Japanese Americans and declared her husband’s policy a violation of basic human rights. Once again, Eleanor served as Franklin’s eyes and ears as she traveled to both Europe and the South Pacific. She observed conditions on the front and offered encouragement to Americans serving overseas.

Franklin died unexpectedly on April 12, 1945. Eleanor announced that she would step down from public life now that she was no longer first lady. That lasted only a few months. President Harry S. Truman appointed Eleanor as a delegate to the newly formed United Nations General Assembly.

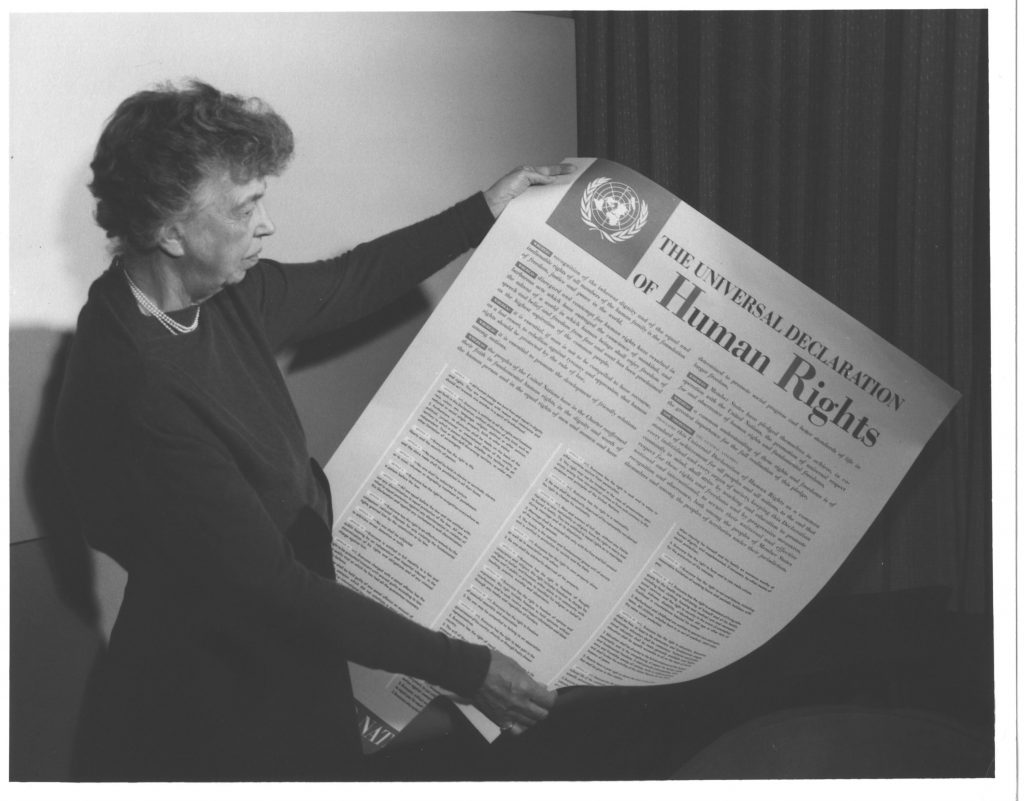

Eleanor did not feel qualified for such an immense position, but the world disagreed. Many already described her as “First Lady to the World.” Eleanor accepted an invitation to serve as chair of the United Nations’ Human Rights Commission. The commission’s task was to draft a document that would define basic human rights. Eleanor was uniquely suited for this work. She knew how to work with men in power and convince them to see alternative perspectives. She had experience fighting for and talking about human rights. She was smart, persuasive, and patient. She believed in equality.

Under her leadership, the commission worked together to create the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They aimed to create a document that all nations could agree upon and that articulated an idealized view of the post-war world. On December 10, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the document. Eleanor described it as one of the greatest achievements of her life.

Eleanor remained involved in the United Nations and other government projects in official and voluntary positions for the rest of her life. Her final appointment came in 1961, when President John F. Kennedy asked her to chair the new President’s Commission on the Status of Women.

On November 7, 1962, Eleanor died in New York City. At the time of her death, she was still writing her weekly column, My Day, and traveling the country speaking about the importance of human rights. Today, she is considered one of the most influential and important people in twentieth-century American history.

Vocabulary

- Black Cabinet: A group of African American activists who advised President Roosevelt on policies relating to Black citizens.

- bolster: Support, strengthen, or reinforce.

- Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR): A social and education membership organization specifically for women directly descended from a person who was involved in the American Revolution.

- diphtheria: A highly contagious bacterial infection.

- fascism: A political philosophy and form of government that promotes a dictatorship and values racial and national unity over individuality and diversity.

- Human Rights Commission: A United Nations committee charged with investigating and defining those human rights that all member nations agree to uphold.

- internment: The state of being confined as a prisoner for political or military reasons.

- Junior League: A charitable organization for young women who wish to volunteer their time and money for social reform issues.

- Marian Anderson: One of the most famous African American singers of the twentieth century.

- New Deal: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s national program for stimulating the American economy during the Great Depression. Included employment, housing, and social service support systems.

- polio: An infectious disease that affects the nervous system and can result in paralysis.

- settlement house: An organization that provided a range of social services to the local community; typically found in poor urban areas.

- social secretary: A person who arranges the social activities and calendar for a person or organization.

- socialite: A person who is active in upper-class or fashionable society. Often refers to a young, single woman in high society.

- United Nations: An international organization formed in 1945. Designed toward the end of World War II to foster cooperation across member countries.

Discussion Questions

- Eleanor was born into a privileged, high-profile family. How did her upbringing shape the rest of her life? What opportunities did she have? What challenges did she face?

- How did Eleanor first become involved in social activism? Why was working in a settlement house significant? How was it different from what was expected of her in society?

- Describe Eleanor’s relationship with her husband, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Why was her marriage so important to her life and career?

- How did Eleanor see her role as first lady? What did she do and why?

- What were some of the issues Eleanor cared most about? What was she able to do to help as first lady?

- Why do you think Eleanor was uniquely qualified to work with the Human Rights Commission? Why do you think she considered it one of her greatest achievements?

- Eleanor is considered one of the most important figures in American history. Why do you think this is the case? What was special about her life and career?

Suggested Activities

- AP Government Connections:

- 2.4: Roles and the powers of the president

- 2.6: Expansion of Presidential Power

- 4.10: Ideology & Social Policy

- 5.3: Political Parties

- Lesson Plan: In this lesson designed for kindergarten through second grade, students will learn about global citizens and the rights they protect. They will use Eleanor Roosevelt’s work on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as an example of global citizenship.

- Lesson Plan: In this lesson designed for eighth grade, students will learn about Eleanor Roosevelt and develop an appreciation for the study of individuals’ lives.

- Lesson Plan: In this lesson designed for eighth grade, students will learn about the formation of the United Nations and the writing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights following World War II. Note: This lesson is designed to build off of the lesson introducing students to Eleanor Roosevelt’s life.

- Both Eleanor and Pauli Murray sought to define what human rights could and should look like in the post-war period. Read both of their life stories and consider how their approaches and philosophies intersected.

- Dive deeper into Eleanor’s work with the UN. Access the full text of the Declaration of Human Rights and listen to an audio clip of Eleanor reading an excerpt aloud on the United Nations’ website here. Also check out the teacher resource Fundamental Freedoms: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Facing History and Ourselves here.

- Eleanor interacted with so many of the women featured in WAMS! Connect her life story to those of Mary McLeod Bethune, Pauli Murray, Dorothea Lange, and Ellen Woodward.

- Eleanor’s life spanned many time periods. Connect this life story to resources in Modernizing America: 1889—1920 to explore her life during the Progressive Era. Also connect her to the Jazz Age, Great Depression, and World War II sections of this unit.

- Eleanor was a longtime opponent of the ERA, although she was often careful not to make her feelings known publicly. Read more about the ERA and consider why she might have taken this stance by reviewing the ERA broadside and ERA pamphlet.

- Eleanor refused to allow the title of first lady to limit her activism and political power. Compare her life story with that of an earlier first lady who also defined the role, Dolley Madison. How did each woman affect change and exercise their roles as unofficial politicians?

- Eleanor started her activist career as a volunteer in a settlement house. Learn more about the settlement house movement by reading Jane Addams’s life story.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; POWER AND POLITICS; AMERICA IN THE WORLD