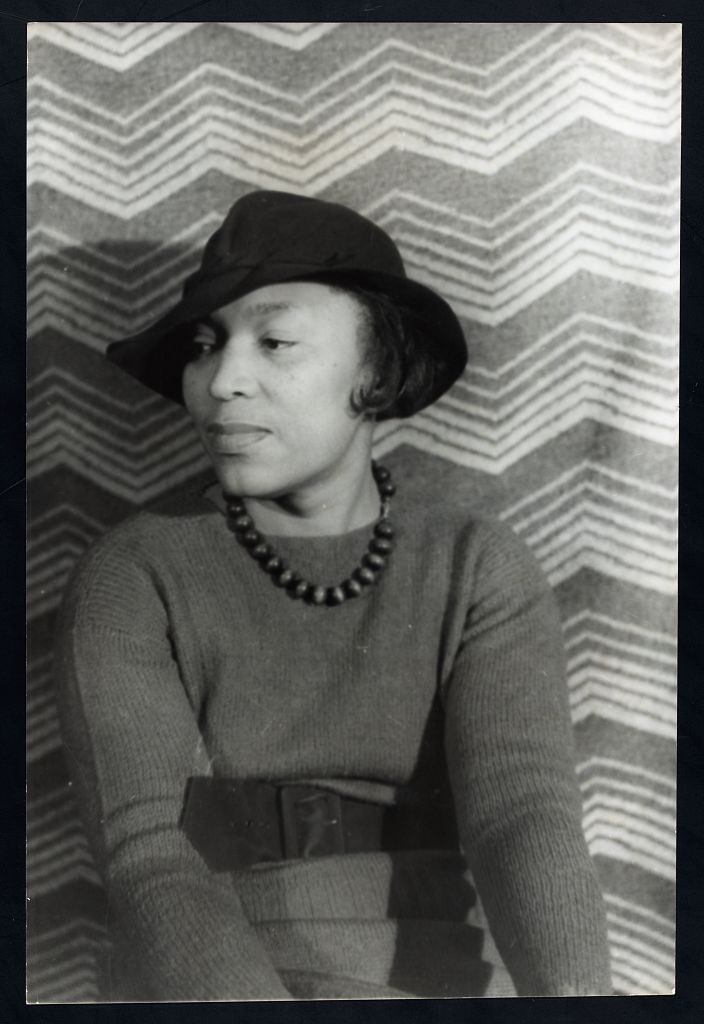

Zora Neale Hurston was born on January 7, 1891 in Eatonville, Florida. Eatonville was one of the first towns in the United States founded by Black citizens. Zora’s father was a minister who served three terms as Eatonville’s mayor. Zora attended the town’s school, where she studied the teachings of Booker T. Washington. She was greatly influenced by the philosophy that education, hard work, and perseverance could improve the lives of Black Americans.

Zora’s mother died in 1904. Her father remarried and sent her to live with relatives. Frustrated by her situation, Zora took a job as a maid for a musical theater troupe in 1916. She traveled the country, learned about theater, and continued her studies by borrowing books from the performers.

After eighteen months of life on the road, Zora quit her job to finish high school in Baltimore. She then enrolled at Howard University, one of the most famous Black colleges in the country. Life at Howard was about more than attending class. Zora was an active participant in campus life. She helped publish the inaugural issue of the school newspaper in 1924 and joined the Howard literary club. Her first two short stories were published in the club’s magazine, The Stylus. Money was a frequent concern for Zora, who paid for school by working as a manicurist at night.

Zora’s big break came in 1925. Opportunity, a Harlem-based magazine, presented her with a literary award for her short story “Spunk.” Zora was thrown into the heart of the Harlem Renaissance. She left Howard University and moved to Harlem. She quickly built a network of colleagues and supporters who recognized her name from Opportunity. That network helped her earn a scholarship to study English and Anthropology at women-only Barnard College. At Barnard, Zora studied under famous anthropologist Franz Boas. Boas encouraged Zora to pursue her interest in African American culture and folklore. Her early fieldwork in Harlem opened doors to travel.

Zora’s creative efforts mirrored her academic studies. She embodied the Harlem Renaissance. She was creative, educated, energetic, and committed to celebrating Black culture. In 1926, she collaborated with other writers to start a magazine called Fire! Some people criticized the magazine for downplaying white supremacy. But Zora and her colleagues felt that there needed to be a place for Black Americans to celebrate their culture without fear.

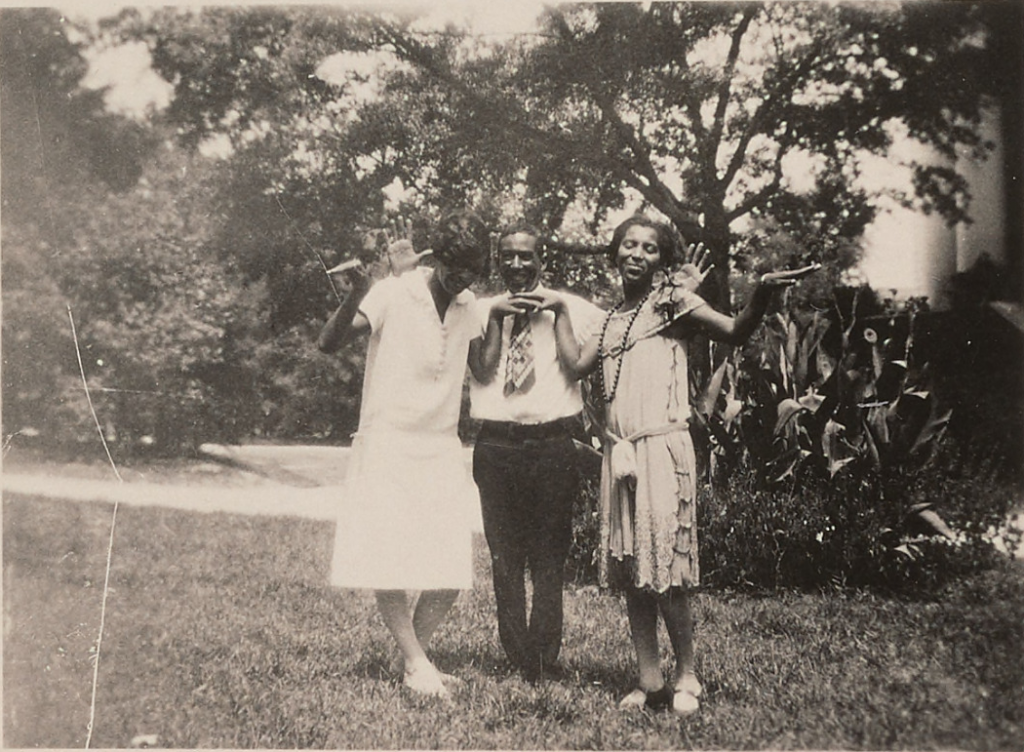

In 1927, Zora met Charlotte Osgood Mason, a white philanthropist who offered to fund Zora’s work. Zora used the funds to plan an elaborate road trip through the American South. During her travels, she conducted interviews, recorded folklore, and collected objects of cultural significance. She spent the spring and summer in Florida. Then she traveled to Alabama to interview the last known living man to be born in Africa and enslaved in America.

While in Alabama, Zora ran into friend and Harlem Renaissance luminary Langston Hughes. Langston and Zora traveled back to New York together, stopping at several cities along the way. They visited the Tuskegee Institute, which was founded by Booker T. Washington. Then, they took a detour to Macon, Georgia, to see Bessie Smith, the “Empress of the Blues,” perform. That evening, they ran into her in their hotel and spent the evening swapping stories of life on the road.

Zora knew that traveling as a single Black woman in the American South was risky. But she considered the South, particularly Florida, her true home, and did not allow her fear to deter her. She felt that her research was too important to give up. Someone needed to document the Black experience for the future.

Using funds from her patron, Zora traveled to Florida and New Orleans to continue her studies in 1928. That same year she earned her undergraduate degree from Barnard.

Now, women forget all those things they don’t want to remember, and remember everything they don’t want to forget. The dream is the truth. Then they act and do things accordingly.

Their Eyes Were Watching God

Although Zora spent much of her time and money on anthropology studies, she did not give up her love of writing. Instead, she used her new knowledge to continue writing plays, short stories, and novels.

In 1930, Zora and Langston Hughes co-wrote a play called Mule Bone. When they disagreed on how much credit each was to receive, the project and their friendship ended. Years later, scholars would argue that the play was a true collaboration by two great talents of the Harlem Renaissance.

Zora survived the Great Depression by publishing fiction while working. She taught theater at the historically Black colleges Bethune Cookman College and Fisk University, and worked as a drama coach for the Works Progress Administration. Zora earned a Guggenheim fellowship to study in Jamaica and Haiti. In 1934, she published Of Mules and Men, an anthropological study of the folklore she gathered during travels through Florida and New Orleans.

At the same time, Zora continued to write fiction. She published her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine, in 1934. In 1937, she published what would become her most famous novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. In both books, Zora explored the lives of Black Americans in the South. Their Eyes Were Watching God was particularly important because it provided insight into the experiences of Southern Black women. She relied on her research to incorporate local dialects and folklore into the novel. Her hope was to create a socially and emotionally realistic depiction of life in her home state of Florida.

Zora’s work in both anthropology and fiction was considered controversial. Some felt that Zora glossed over the violent racism and suppression Black Americans faced. They also worried that her portrayal of Southern Black dialects and folkways out of context furthered racist stereotypes. Others did not like that Zora often created violent characters in her plays and novels who were also sympathetic. As an author and social scientist, Zora sought to present the world as she saw it. She did not believe it was her role to pass judgment.

The 1940s and ’50s were a challenge for Zora. She published an unsuccessful novel and a popular autobiography. However, none of her writing brought much financial success. Zora resorted to taking odd jobs as a maid, teacher, journalist, and clerk to pay her bills. As the Black civil rights movement expanded in the United States, new generations of activists questioned her work. Her publications were often dismissed as too traditional and narrow by new generations of Black activists.

In 1959, Zora suffered a stroke. She had very little money and moved into the St. Lucie County Welfare Home in Florida. On January 28, 1960, she died of heart complications and was buried in an unmarked grave. Although relatively unknown at her death, Zora was an important female voice in the largely male literary world of the Harlem Renaissance. Her work inspired—and continues to inspire—future generations of artists, authors, and anthropologists.

Vocabulary

- anthropology: The scientific study of human society and culture.

- Bessie Smith: A famous African American singer known as the “Empress of the Blues.” See her life story for more.

- fellowship: A temporary job associated with a college or other academic organization. Fellowships often give individuals times to conduct research or create new work without limitations while being paid.

- folklore: Traditional beliefs, customs, and stories. Often passed through families and communities by word of mouth.

- Franz Boaz: A German American anthropologist who worked at Columbia University. Often called the “Father of Modern Anthropology.”

- Harlem Renaissance: A term used to describe the intellectual, artistic, and creative output of African Americans in Harlem in the 1920s.

- inaugural: The first or beginning of something.

- Langston Hughes: A famous Harlem Renaissance poet, novelist, playwright, and activist.

- literary club: A club or group that studies and writes literature and poetry.

- manicurist: Someone who gives manicures and pedicures in a salon or barbershop.

- philanthropist: A wealthy person who donates significant amounts of money to charity.

- Tuskeegee Institute: An African American school for higher education and job training. One of the first of its kind. Founded by activist Booker T. Washington in Alabama in 1881.

- white supremacy: The racist belief that white people are superior to people of color.

Discussion Questions

- How was Zora’s career and view of the world shaped by her childhood? What was special about Eatonville and its school?

- What was the Harlem Renaissance and how did Zora contribute to this important moment in American history?

- Despite being a luminary of the Harlem Renaissance, Zora was relatively unknown and very poor when she died. Why do you think she fell out of the spotlight so quickly?

- Why was Zora’s work considered controversial? What does this tell you about the state of race and culture in America in this era?

Suggested Activities

- Zora was influenced by the teachings of Booker T. Washington at an early age. Encourage students to research his philosophy and consider how it may have shaped Zora’s life.

- Zora was one of thousands of women to relocate to Harlem from the South. Learn more about women’s experiences using the photographs of the Great Migration.

- Compare Zora’s life to that of Bessie Smith. Both women were born in the South and traveled extensively. They even met once! How were their lives similar and different, and how do they each exemplify life in the Jazz Age?

- Consider Zora’s life—and death—within the broader context of race relations in the 1920s. Combine this life story with the Great Migration photographs, the WKKK document, and the life story of Bessie Smith to go deeper.

- Deepen your understanding of this history by exploring the Harlem resources in our Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow curriculum.

- Compare Zora’s life with that of Pauli Murray. Both women studied at Howard University. What were their experiences like? Why was it important for them to attend a historically Black school?

Themes

AMERICAN CULTURE