Document Text |

Summary |

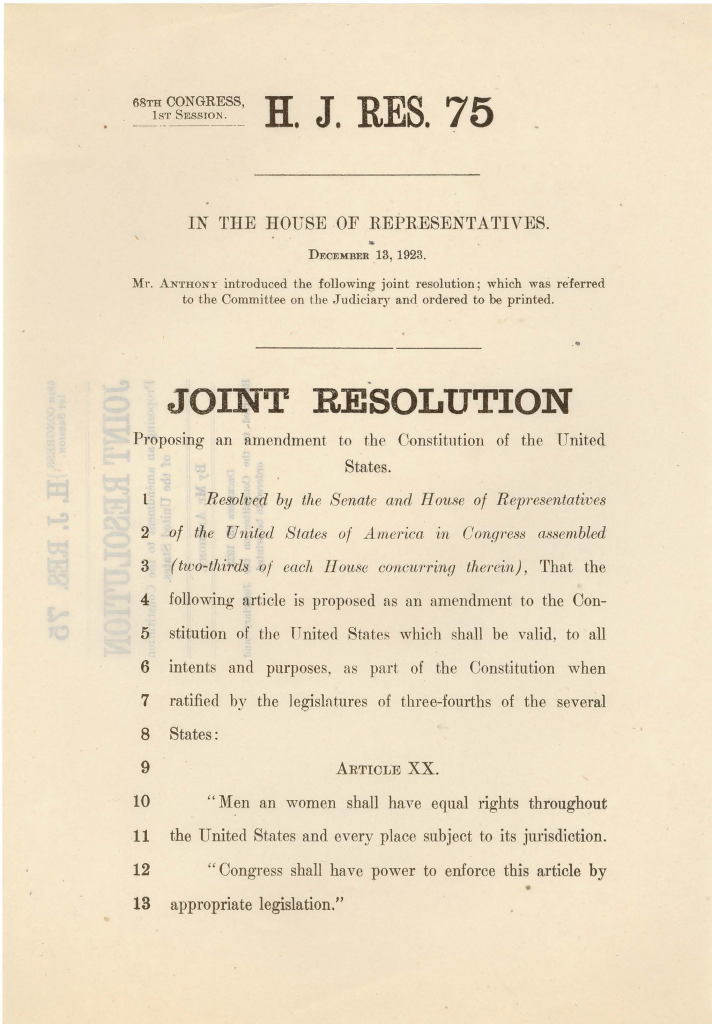

| JOINT RESOLUTION

Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States |

This document is a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States. |

| Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled (two-thirds of each House concurring therein), That the following article is proposed as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the Constitution when ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States: | This document is presented to the Senate and the House of Representatives. The proposed amendment will only be part of the Constitution if three-fourths of legislators in both the Senate and the House vote in favor of it. |

| ARTICLE XX. | |

| “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” |

Men and women will have equal rights across the country and in its territories. |

| “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” | Congress will enforce these equal rights with laws. |

“Proposing an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution,” December 13, 1923, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, 1789 – 2015 Series. National Archives and Records Administration.

The Equal Rights Amendment and Protective Legislation: Will the Equal Rights Amendment Affect Protective Legislation for Women?, pg. 1

National Woman’s Party, “The Equal Rights Amendment and Protective Legislation: Will the Equal Rights Amendment Affect Protective Legislation for Women?,” ca. 1923. University of Virginia Library.

The Equal Rights Amendment and Protective Legislation: Will the Equal Rights Amendment Affect Protective Legislation for Women?, pg. 2

National Woman’s Party, “The Equal Rights Amendment and Protective Legislation: Will the Equal Rights Amendment Affect Protective Legislation for Women?,” ca. 1923. University of Virginia Library.

Document Text |

Summary |

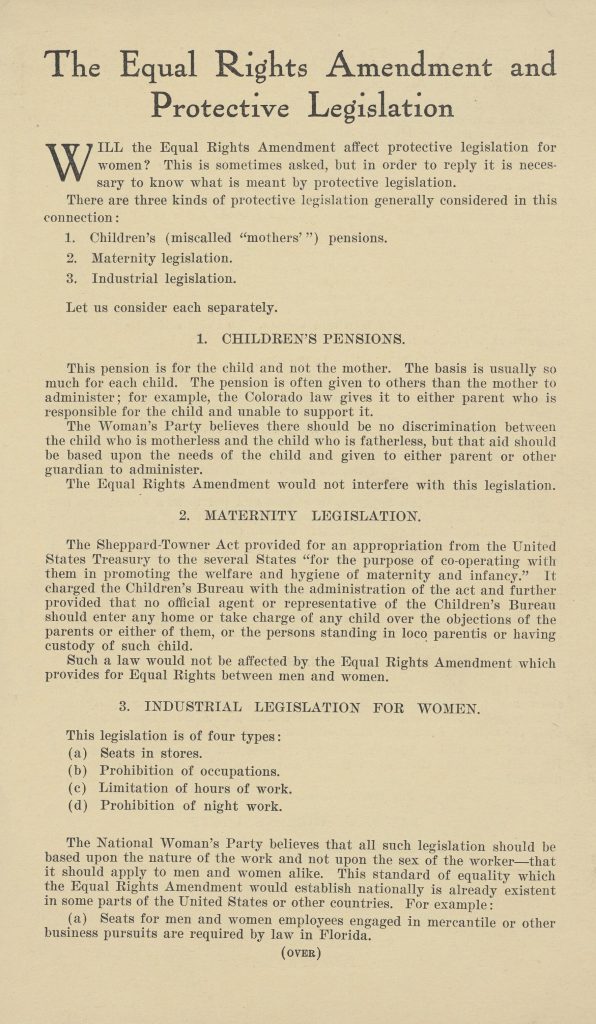

| The Equal Rights Amendment and Protective Legislation Will the Equal Rights Amendment affect protective legislation for women? This is sometimes asked, but in order to reply it is necessary to know what is meant by protective legislation. |

This document is about the connections between the Equal Rights Amendment and protective legislation. |

| There are three kinds of protective legislation generally considered in this connection: 1. Children’s (miscalled “mothers’”) pensions. 2. Maternity legislation. 3. Industrial legislation. Let us consider each separately. |

There are three kinds of protective legislation. First, children’s pensions. Second, maternity legislation. Third, industrial legislation. |

| 1. CHILDREN’S PENSIONS. | |

| This pension is for the child and not the mother. The basis is usually so much for each child. The pension is often given to others than the mother to administer; for example, the Colorado law gives it to either parents who is responsible for the child and unable to support it. | Children’s pensions provide a certain amount of money to parents who need additional financial support. |

| The Woman’s Party believes there should be no discrimination between the child who is motherless and the child who is fatherless, but that aid should be based upon the needs of the child and given to either parent or other guardian to administer. | The Woman’s Party supports children’s pensions and likes that pensions can be given to mothers, fathers, or other guardians. |

| The Equal Rights Amendment would not interfere with this legislation. |

The Equal Rights Amendment would not affect children’s pensions. |

| 2. MATERNITY LEGISLATION |

|

| The Sheppard-Towner Act provided for an appropriation from the United States Treasury to the several States “for the purpose of co-operating with them in promoting the welfare and hygiene of maternity and infancy.” It provided that no official agent or representative of the Children’s Bureau should enter any home or take charge of any child over the objections of the parents or either of them, or the persons standing in loco parentis or having custody of such child. | The Sheppard-Towner Act was a law that provided financial support for mothers and babies in need. It also ensured that babies in need would stay with their families. |

| Such a law would not be affected by the Equal Rights Amendment which provides for Equal Rights between men and women. |

Laws that protect mothers, fathers and babies would not be affected by the Equal Rights Amendment. |

| 3. INDUSTRIAL LEGISLATION FOR WOMEN | |

| This legislation is of four types: (a) Seats in stores. (b) Prohibition of occupations. (c) Limitations of hours of work. (d) Prohibition of night work. |

Industrial legislation protects workers in multiple ways, including limiting work hours and creating safe work environments. |

| The National Woman’s Party believes that all such legislation should be based upon the nature of the work and not upon the sex of the worker – that it should apply to men and women alike. This standard of equality which that Equal Rights Amendment would establish nationally is already existent in some parts of the United States or other countries. For example: |

The National Women’s party believes that protective legislation should be in place for both men and women. There are many examples in the states of laws that promote this type of equality.

Some examples are described below. |

| (a) Seats for men and women employees engaged in mercantile or other business pursuits are required by law in Florida. | In Florida, businesses are required to provide seats for both men and women workers. |

| (b) That no one should be disqualified on account of sex from entering into or pursuing any lawful business, vocation, or profession is provided in the constitution of California. | In California, businesses cannot refuse to hire someone based on their sex. |

| (c) A ten-hour law for all persons, men and women alike, in mills, factories and manufacturing establishments, is found in Oregon. Mississippi and Georgia have ten-hour laws for all persons, men and women alike, in manufacturing industries. Eight-hour laws for persons, men and women alike, in certain specified occupations, are found in over thirty States. | In Oregon, mills, factories, and manufacturing plants must maintain ten-hour workdays for men and women employees. In Mississippi and Georgia, manufacturing plants must maintain ten-hour workdays for men and women employees. Over thirty states have eight-hour workday laws for men and women. |

| The demand for a shorter work-day is based upon the need of leisure, health, recreation, and the fulfilling one’s duties to society. These needs bear no relation to sex and the laws which provide for a shorter work-day should therefore be regardless of sex. |

A shorter workday is important for men and women. There is no reason for such laws to target only one sex. |

| (d) While the regulation of night work has been applied to men and women alike in some places, as Norway, in sixteen of the United States it applies to women only. The arguments of the Attorney-General upholding the New York night-work law were based on extensive investigations, both here and in Europe. The law applies to women only, but the arguments and investigations apply to both men and women. To summarize, they declared night work injurious because – (1) Artificial light is injurious to the eyes. (2) Sleep in the daytime is more broken than at night. (3) It tends toward greater smoking, drinking, and swearing. (4) Lack of sunshine tends to anemia and tuberculosis and weakens the procreative power of men as well as the generative functions of women. |

Sixteen states have laws preventing night work for women. But the reasons for barring women from night work can also be applied to men. Night work is dangerous to employees’ eyes. Sleeping during the day less restful. People who work at night are more likely to smoke, drink, and swear. Not getting enough sunlight can lead to health problems. |

| The Equal Rights Amendment would require that all these industrial laws be made to apply to men and women alike, but the standards adopted would be left to the States. | The Equal Rights Amendment would require that all industrial laws be applied to men and women. |

| Industrial laws when applying to women and not to men are among the gravest discriminations against women. They close many doors of opportunity to women seeking employment. Women thrown out of work by their passage are invariably forced into harder, more poorly paid work, as scrubbing floors, for which they must compete with one another. |

Industrial laws directed only at women are discriminatory. It limits women’s employment options. Many women lose their jobs when such laws are passed. |

| This legislation, with its linking of women with children instead of with adults, began years ago in the transition stage of women’s much protested invasion of industry. Today when women are an established and increasingly important part of our economic life, justice requires that legislation concerning them be on the same basis as that for their male competitors. |

Such laws treat women more like children than adults. Women are an important part of the economy and deserve fair treatment. |

| CONCLUSION. |

|

| The Equal Rights Amendment would not interfere with children’s pensions nor with legislation, such as the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act. It would, however, required that all industrial laws be based upon the nature of the work and not upon the sex of the worker. |

The Equal Rights Amendment will not change children’s pensions or maternity legislation. It will require industrial laws to change, but those changes will be for the better. |

| The Equal Rights Amendment reads: “Men and women shall have Equal Rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” |

The Equal Rights Amendment declares men and women shall have equal rights in the United States. |

| For further information apply to NATIONAL WOMAN’S PARTY Alva Belmont House, Washington, D.C. |

This document was written by the National Woman’s Party. |

National Woman’s Party, “The Equal Rights Amendment and Protective Legislation: Will the Equal Rights Amendment Affect Protective Legislation for Women?,” ca. 1923. University of Virginia Library.

Background

After passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, women activists were divided on where to focus their efforts. The League of Women Voters led voter registration and education. The National Woman’s Party (NWP) drafted legislation and promoted women candidates. The NWP’s primary goal was securing an amendment to the Constitution that declared men and women equal under the law. In 1923, NWP President Alice Paul drafted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

The ERA was controversial from the beginning. Many of the nation’s most ambitious women activists worried that the NWP went too far. They argued that the ERA was unrealistic and a threat to important protective legislation. Protective legislation included limits on the number of hours women worked and bans on night work. Such laws provided important supports for women, particularly lower-class mothers and workers.

There were two major types of opponents to the ERA. The first were traditionalists who genuinely did not believe men and women were equal. They argued biological differences proved that social roles for men and women should be different. The second group of opponents believed in equality, but argued the ERA did not address the needs of real women who needed government intervention. Fighting for full equality was a privilege most women could not afford. NWP members, however, believed that protective legislation was demeaning to women and that workplace and other protections should not be based on gender but on need. They argued it was better to secure equal status under the law and then fight for improved social services and revised protections. This debate would continue for decades.

The extreme division among activists prevented the ERA from gaining momentum in 1923. Although the concept never fully disappeared, it would return to a major stage in the 1970s. And, even then, it would prove to be a controversial idea.

About the Document

The first document is the Equal Rights Amendment drafted by Alice Paul, a suffrage leader who founded the National Women’s Party. This draft was presented to Congress by Representative Daniel Anthony of Kansas in December 1923.

The second document is a broadside printed by the NWP and explains why members believe the ERA benefits women and does not destroy the benefits of protective laws.

Vocabulary

- amendment: A change or addition.

- candidate: A person running for office.

- demeaning: Insulting or humiliating.

- Equal Rights Amendment (ERA): A proposed amendment to the United States Constitution stating that rights may not be denied on the basis of a person’s sex.

- League of Women Voters: An activist group that was founded in 1920. Prior to 1920, it was known as the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

- National Woman’s Party: An activist group and political party founded by Alice Paul and other suffragists who separated from the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1916.

- protective legislation: Laws that are intended to protect a specific group of people from dangers, abuse, or mistreatment.

- voter registration: The process an eligible person must complete in order to vote in an election.

Discussion Questions

- What does the Equal Rights Amendment say? What do you make of the fact that the amendment is two sentences long?

- Why was protective legislation the biggest factor in the debate over the Equal Rights Amendment?

- How does the National Woman’s Party explain its position in the second document? How do they define protective legislation? Why do they believe the Equal Rights Amendment will not destroy the benefits of protective legislation?

- How might an Equal Rights Amendment opponent feel about the NWP document? What counterarguments could they make?

- Women activists were divided on whether it was better to push for the principle of equal rights (through a Constitutional amendment) or to have unequal but effective laws (protective legislation). What do you think about this debate? Can you think of other examples from American history where activists had to choose between fighting for full equality and achieving small steps via compromise?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 7.8: 1920s: Cultural & Political Controversies

- AP Government Connections:

- 1.7: Relationship between the states and the federal government

- 4.7: Ideologies of Political Parties

- 4.10: Ideology & Social Policy

- Compare the activities of the two largest women activist organizations of the decade by looking at these documents alongside the League of Women Voters’ posters.

- Deepen your understanding of this debate by reading about Progressive Era protective legislation and the Muller v. Oregon decision.

- Consider how working class women might have felt about the debate over the Equal Rights Amendment. Read Ella May Wiggins’s life story. How do you think this working mother would have felt about the National Woman’s Party’s argument?

- Consider how African American activists might have felt about this debate. Read the life stories of Mary McLeod Bethune, Mary Church Terrell, and Ida B. Wells. How do you think these women might have felt about the ideals of the Equal Rights Amendment?

Themes

ACTIVISM, VOTING, POLITICS & GOVERNMENT, CIVIL RIGHTS