This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Anna May Wong was born Wong Liu Tsong on January 3, 1905 in Los Angeles, California. She was the second of her parents’ seven children. Anna’s family lived in the back of her parents’ laundry business just outside of Chinatown. Anna and her siblings worked for hours each day in the family laundry.

Anna’s mother was born in San Francisco and her father was born in a California gold mining town. But like most Asian Americans in this era, the Wong family was treated like outsiders. Anna’s parents owned a laundry because it was one of the few work options available to Chinese Americans. Anna and her older sister attended a predominantly white California Street public school. The students bullied them for being Chinese American. Students would push Anna, pull her hair, slap her face, and call her offensive names like “Chink” and “Chinaman.” Anna described it as torture.

Anna’s parents transferred the girls to the nearby Chinese Mission School in Chinatown. Anna’s classmates were all Chinese American, and she was not bullied. Anna studied English and Cantonese. She excelled at learning English, but her Cantonese was not as strong. Anna’s parents were disappointed their daughter spoke Cantonese with an American accent.

At a young age, Anna was fascinated with the movies. She used the tips she earned delivering laundry to buy movie tickets. She also frequently skipped school to watch movies being filmed on the streets of Chinatown. When Anna was 14, she got her first part in a movie. She was an extra in The Red Lantern. Although she had no lines and no official credit recognition, she decided it was the beginning of a big career.

Anna continued to take whatever roles she could find. By 1921, she dropped out of school to pursue acting full-time. It was around this time that she changed her name to Anna May Wong.

Anna’s big break came when she was 17. She played a lead character in the silent film The Toll of the Sea. From there, the jobs increased. Anna took on bigger and bigger roles and had a following of fans. But her parts were still limited. Anna faced three major hurdles. First, most audiences wanted to see Asian women portraying stereotypes, as either Butterflies—passive young women—or Dragon Ladies—murderous villainesses. Second, many states across the country had anti-miscegenation laws that prohibited interracial couples from appearing on screen. Anna could not play a character in love with a non-Asian actor. Third, it was common for white actresses to play Asian characters in yellowface. Anna often competed against non-Asian women for Asian parts.

Although Anna’s roles were limited, she became wildly popular with viewers of diverse backgrounds. Asian Americans were thrilled to see an Asian person on screen. White audiences saw her as an exotic “Oriental.” Even though she often played stereotypes, she also showed viewers that Asian women could be successful professionals.

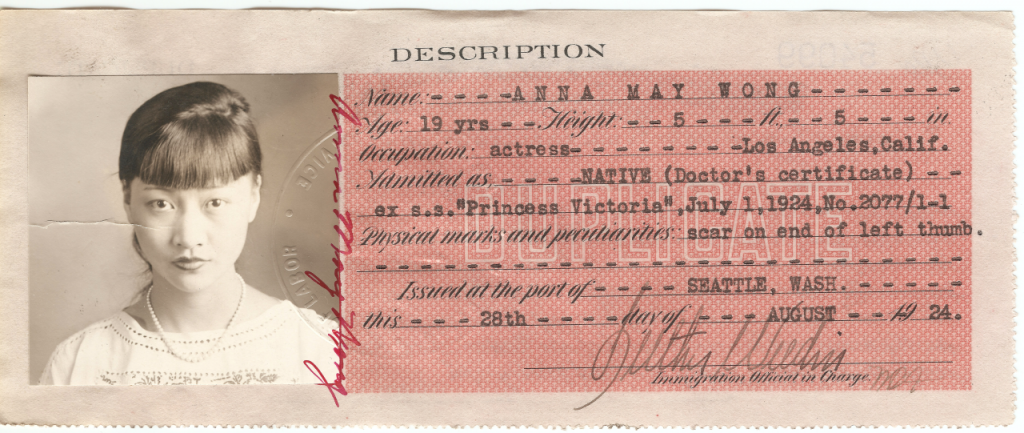

But being Chinese American in the United States was a challenge. Under the Chinese Exclusion Act, all people of Chinese descent had to carry identification papers proving they were allowed to be in the country. Even when Anna’s face was on billboards and movie screens across the country, she had to constantly prove her citizenship.

There seems little for me in Hollywood, because, rather than real Chinese, producers prefer Hungarians, Mexicans, American Indians for Chinese roles.

To fight off prejudice, Anna adopted a flapper lifestyle. She was independent, free spirited, and energetic. She posed for portraits that presented her as an all-American woman and a glamorous Hollywood starlet. But the fight to prove herself was exhausting.

In 1928, Anna accepted an offer to star in a movie in Berlin. She hoped that European audiences would be more open to an Asian movie star. When she left, she joked that she was moving to Europe because she was tired of playing innocent or evil characters who died.

Anna found success in Europe, working in Germany, France, and England. She appeared on the cover of magazines and interacted with other American artists living abroad, including Josephine Baker. She even learned to dance and sing on stage, something she had not done in the United States. Still, most of Anna’s roles were typecast. Anna was often asked to play generic “Oriental” characters that combined Asian stereotypes. In one of her most famous movies, Picacdilly, she performed a Siamese dance.

By the 1930s, Anna worked around the globe. She continued to find success in Europe, but often returned to Hollywood. In 1935, Anna auditioned for the film adaptation of Pearl Buck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book about Chinese farmers, The Good Earth. The book was a national best seller and the movie was expected to be a huge hit. But the part was given to Luise Rainer, a white actress in yellowface. Anna was devastated.

Motivated by this huge setback, Anna visited China for the first time in her life. Anna wanted to learn more about the home of her ancestors, but many Chinese people criticized her for playing racist roles on screen. Anna tried to mend relations with the people of China by becoming an advocate for the country. She arranged for her journey to be filmed so that American audiences could see China through her eyes. And during World War II, she raised money for Chinese refugees.

Anna’s career began to fade after the war. Tastes were changing, and Anna was no longer able to play the young Asian stereotypes that had brought her success in the past.

The next few decades were full of highs and lows. After years of struggle and little work, Anna was the first Asian American to star in her own television series. But the show was canceled after one season. Anna’s health also began to fail. Anna was drinking too much, and her liver and heart suffered.

In 1961, Anna hoped a role in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song would be her great comeback to the big screen. Unfortunately, she never made it to set. Anna became very sick, and doctors ordered her to stay in bed. On February 3, 1961, she died of a heart attack in her sleep.

Vocabulary

- Josephine Baker: An African American singer and dancer who escaped racism in the United States and found fame in France.

- miscegenation: The mixing of different racial groups through romantic and sexual relationships.

- Oriental: A general term for people or things from East Asia. It is widely considered offensive.

- Rodgers and Hammerstein: One of the most famous partnerships in musical theater writing and producing in the 1940s and ‘50s.

- Siamese: A person or thing from the country Siam (now Thailand).

- silent film: A film or movie without sound. All movies before 1927 were silent films.

- stereotype: A popular but oversimplified version of a type of person or thing. Stereotypes are often offensive and meant to mock the subject.

- typecast: Assigning someone to the same type of role, which is usually based on stereotypes and physical appearance.

- yellowface: A non-Asian actor portraying an Asian character in a movie or play.

Discussion Questions

- How was Anna’s life shaped by anti-Asian policies and attitudes?

- What types of discrimination did Anna face throughout her life, and what actions did she take to avoid such treatment?

- Why did Anna adopt a flapper lifestyle? What does this say about her personality and her goals?

- Anna had a semi-successful career in Hollywood in the 1920s. Why did she choose to move to Europe in 1928?

- Anna faced criticism in China. What did people dislike about her work? What counterarguments could she have made about her career choices?

Suggested Activities

- Learn more about the experiences of Chinese Americans by pairing this life story with the resources in Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion.

- Pair Anna May Wong’s life story with that of Edith Maude Eaton, who reported on the lives of Chinese Americans during the Progressive Era.

- Have students analyze the three different images of Anna presented here. How does each portray a different aspect of her life? Pair these images with others, include the flapper magazine covers and flapper photographs to deepen the conversation.

- Anna May Wong was not the only actress of color who played offensive roles in order to have a career. Encourage students to research Hattie MacDaniel, Lupe Velez, and Dolores del Rio to broaden the conversation. How did each actress pursue her career and deal with these challenges?

- Compare Anna May Wong’s life story with current discussions about Asian American actors today. Show students examples of the media surrounding Crazy Rich Asians or the yellowface controversy around the movie Aloha.

- Yellowface is not limited to the movies. After learning about this issue through Anna May Wong’s life story, encourage students to visit the website yellowface.org to learn how performing artists today are tackling yellowface in the performing arts.

Themes

AMERICAN CULTURE; AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP