Eliza Brock was a white woman born around the year 1779 in Pennsylvania. When she was about 14 years old, she worked as a domestic servant in Philadelphia. Domestic servants did the hard labor necessary to keep a home running. Eliza probably spent her days cleaning, doing laundry, and running errands for her employers. It was one of the only respectable paying jobs available to young women in the Federal period.

In the summer of 1793, Philadelphia suffered a severe outbreak of yellow fever. At the time, no one knew mosquitos carried the virus, so they had no way to protect themselves. About 5,000 of the city’s 45,000 residents died before the outbreak ended. White people who had money, including Eliza’s employers, fled the city. They left Eliza behind with their Black servants to take care of their home.

One day, while Eliza was out fetching water, she was called to the home of a neighbor named John Todd. John was ill with yellow fever. He asked Eliza to buy him some fruit at the local market so he would have something to eat. Eliza cared for him until the illness took his life. Shortly after he died, Eliza’s father arrived and took her out of the city to protect her from the virus.

While living in Susquehanna County, Eliza married her first husband. He died soon after, and she remarried a German immigrant named Frederick Brock. Frederick was a prosperous farmer and landowner. Eliza lived a comfortable, middle-class life and gave birth to a daughter and son. This happy period was marred by the death of her daughter in 1828.

Things became much more challenging for Eliza in her later years. Her adult son died of smallpox in 1841, leaving his wife and two children behind. Her daughter-in-law died a year later, leaving both children in Eliza and Frederick’s care. Unfortunately, Frederick died just one year later, leaving Eliza a widow with two small grandchildren.

When she was married, Eliza had no legal existence as a person separate from her husband.

Like all white American women, Eliza Brock’s life was governed by rules and customs of coverture. When she was married, Eliza had no legal existence as a person separate from her husband. Frederick was solely responsible for the family’s land and money. When he died, she inherited the property and all the debts he left behind. But without a living husband or son, she was forced to manage it all on her own. When Frederick’s debts proved too great to repay, she had no way to earn money while maintaining her status as a middle-class housewife.

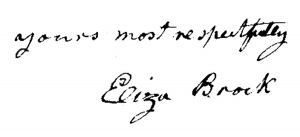

On February 21, 1844, Eliza took an unusual step to try to solve her financial troubles. She wrote a letter to Dolley Madison, the former First Lady and one of the most respected women in America. Eliza explained how challenging her life had become since the death of her husband and asked Dolley for help. She had reason to hope the former First Lady might take pity on her. John Todd, the man Eliza cared for while he died of yellow fever in 1793, was the father of Dolley’s first husband. This letter is why historians know so much about Eliza’s life.

Unfortunately, Dolley Madison was in no position to help Eliza. Her public reputation was still golden, but in private she was elderly, ill, and financially insecure. Dolley lost most of her former wealth paying off her son’s gambling debts. Just like Eliza, she was a widow who had no respectable way to earn money without losing her status. A few years before Eliza sent her letter, Dolley resorted to selling her enslaved people against her late husband’s wishes to make ends meet. The day before Eliza wrote her letter, Dolley wrote one herself, asking an unnamed person where she might borrow $200.

The last record of Eliza Brock appears in U.S. Census records of 1850. This was the first year women, children, and enslaved people were recorded in a U.S. census. According to the census, Eliza was 73. She was living on her farm with her 13-year-old grandson, 11-year-old granddaughter, and a woman in her twenties who may have been a servant or a boarder. There are no men listed who might have worked the farm. In response to one of the census questions, Eliza set the value of her property at $1,500. Among her close neighbors, she was neither the richest nor the poorest. Somehow, she managed to hold on to the family farm and her position as a middle-class woman.

Vocabulary

- census: An official count of a country’s population. The U.S. Census is taken every 10 years.

- coverture: A common law practice where women fell under the legal and economic oversight of their husbands upon marriage.

- Federal period: The early years of the United States, usually defined as 1790–1830.

- yellow fever: A deadly virus that affects the liver and kidneys.

Discussion Questions

- What challenges did Eliza face in her lifetime?

- Why did Eliza seek Dolley Madison’s help in 1844?

- What does this story reveal about the lives and experiences of middle-class white women in the Federal period?

Suggested Activities

- To help students better understand the social limitations Eliza Brock lived under, read Republican Motherhood.

- There is no record of whether Dolley Madison ever wrote back to Eliza Brock. Ask students to read Dolley’s life story, and then write how they imagine the former First Lady might have responded.

- Teach the following life stories together with Margaret’s story to create a more complicated picture of women in the early years of the nation’s capital: Life Story: Dolley Madison, Life Story: Margaret Bayard Smith, and Life Story: Sukey.

- For a larger lesson about the implications of coverture for women, teach this life story together with the following: Life Story: Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas, Coverture, The Will of Joseph Grover, Reaffirming Coverture, and Life Story: Dolley Madison.

Themes

DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- To learn more about Eliza Brock’s interactions with Dolley Madison, see Saving Washington: The New Republic and Early Reformers, 1790-1848.