Document Text |

Summary |

| I long to hear that you have declared an independency — and by the way in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation. |

I can’t wait until you declare independence from England. I guess you’ll need to write a constitution for the new country. Please write better laws for women. Don’t give men unlimited power over their wives. Men can be bullies, and women need to be able to protect themselves. If you don’t write better laws for women, we’ll have our own revolution. We won’t submit to a government that does not let us have a say. |

| That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your sex. Regard us then as beings placed by providence under your protection and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness. |

Everyone knows men are bullies, and that it is only good men who choose to treat their wives and daughters fairly. Why would you write laws that give men the power to treat women badly without consequences? Smart men hate that women are treated inferior to men. Instead, think of us as people that God wants you to protect, and use your power to give us better lives. |

“Abigail Adams to John Adams,” March 31, 1776. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Document Text |

Summary |

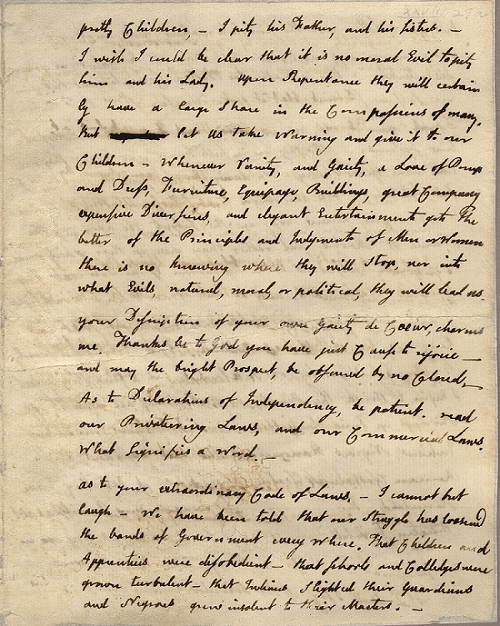

| As to your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our struggle has loosened the bands of Government everywhere. That children and apprentices were disobedient — that schools and colleges were grown turbulent — that Indians slighted their guardians and negroes grew insolent to their masters. | Your idea to make the laws fairer to women made me laugh. We’re heard that the revolution has inspired many people to rise up against unfairness. Children don’t listen to their parents. Apprentices don’t obey their masters. Students at schools and colleges are wild. Indigenous people are ignoring white governors, and enslaved people are rebelling against their enslavers. |

| But your letter was the first intimation that another tribe more numerous and powerful than all the rest were grown discontented. — This is rather too coarse a compliment, but you are so saucy, I won’t blot it out. | But your letter is the first time I heard that women are planning to rebel too. I’m being very rude, but your letter was so saucy I won’t cross it out. |

| Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory. We dare not exert our power in its full latitude. We are obliged to go fair, and softly, and in practice you know we are the subjects. We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave heroes would fight. I am sure every good politician would plot, as long as he would against despotism, empire, monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy, or ochlocracy. — a fine story indeed. I begin to think the ministry as deep as they are wicked. After stirring up Tories, Landjobbers, Trimmers, Bigots, Canadians, Indians, Negroes, Hanoverians, Hessians, Russians, Irish Roman Catholics, Scotch Renegades, at last they have stimulated the ladies to demand new privileges and threaten to rebel. | We know better than to give women more power. You know men aren’t really in charge, even if the law says so. We have to follow what women say already. If women try to fight for more equality, I hope George Washington and the army would fight back. Every politician would too. I wonder if this is part of a British plot. Now that they’ve turned every other group against us, they are getting women to rebel too. |

“John Adams to Abigail Adams,” April 14, 1776. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Document Text |

Summary |

| I cannot say that I think you very generous to the ladies, for whilst you are proclaiming peace and good will to men, emancipating all nations, you insist upon retaining an absolute power over wives. But you must remember that arbitrary power is like most other things which are very hard, very liable to be broken — and notwithstanding all your wise laws and maxims we have it in our power not only to free ourselves but to subdue our masters, and without violence throw both your natural and legal authority at our feet. | I don’t think you are treating women well. You talk about the ideals of liberty, but you insist on keeping women subordinate to men. But remember, absolute power is easily overthrown. Your wise laws will not protect you if we decide to rebel and subdue you instead. |

“Abigail Adams to John Adams,” May 7-May 9, 1776. Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Background

In 1774, Massachusetts politician John Adams was selected to attend the newly formed Continental Congress in Philadelphia as one of four delegates from his state. He would play a critical role in forming the United States of America and its government. Like many men who were swept up in the events of the American Revolution, he left his wife, Abigail, to manage their farm, tend their home, and raise their five young children. Abigail also found time to follow all the unfolding events of the revolution. She wrote her husband long letters that contained a mix of news about her home life as well as her thoughts on the political crisis.

In the spring of 1776, Abigail knew that John and the Congress were planning to declare independence from England. She frequently asked for news of their progress and shared her thoughts on how the Congress should move forward.

About the Document

These documents are three excerpts from Abigail and John Adams’s correspondence in 1776. They show that Abigail viewed the formation of a new nation as a chance to free women from the limitations of coverture. Her request that John “remember the ladies” was not a demand for suffrage or political rights. She wanted the new government to give women some autonomy so that they were not under the legal control of their husbands and fathers. John’s patronizing dismissal of her concerns is typical of male attitudes towards women’s ideas and desires in the Federal period.

Vocabulary

- Continental Congress: The legislative assembly that oversaw the government of the colonies and the execution of the war effort during the American Revolution.

- coverture: A common law practice where women fell under the legal and economic oversight of their husbands upon marriage.

- suffrage: The right to vote.

Discussion Questions

- Why does Abigail want John to seize this opportunity to change women’s legal standing?

- How does John respond to Abigail? How does this make you feel? How do you think Abigail felt reading it?

- What is Abigail’s warning to John? What does this reveal about her feelings?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.4: Philosophical Foundations of the American Revolution

- Ask students to read Growing Frustration and write a paper linking Abigail’s warning to John with the Virginia Freewoman’s frustrations in 1829.

- The Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution did not specifically mention women. To learn more about how the legal status of women evolved in the Federal period read Reaffirming Coverture and New Jersey’s Suffrage Experiment.

- For a larger lesson about how women’s legal rights were deliberately limited by the U.S. government, pair this document with The Other Thirteenth Amendment.

- To help students understand how coverture could be a detriment to women in the United States, use:

Coverture, Life Story: Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas, All Bound Up Together, Life Story: Dolley Madison, Life Story: Eliza Brock, Expanding Women’s Roles and Fighting Public Evils, Waged Work and Protective Laws, Together for Home and Family, Married Women and Work, and Ruling to Protect Women.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; POWER AND POLITICS