This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Ona Judge Staines was born in April 1774. Her mother, Betty Davis, was an enslaved Black woman held by George and Martha Washington at their plantation, Mount Vernon, in Virginia. Her father, Andrew Judge, was a white indentured servant who worked on the same plantation. It is not known whether Betty and Andrew’s relationship was consensual.

Even though her father was a free white man, Virginia law stated that Ona inherited the status of enslaved person from her mother. As a young child, Ona assisted her mother and did small jobs around the plantation. She must have been a hard worker because when she was 12 years old Martha brought her into the main house and began training her as a housemaid. This was an improvement in status, but the work was still very difficult.

In 1789, George Washington was elected as the first president of the United States. Over the next eight years, he moved his household to New York City and then to Philadelphia. Sixteen-year-old Ona was one of only nine enslaved people chosen to move with the Washingtons to the presidential mansion. It must have been difficult for Ona to leave her mother and siblings behind, but she had no choice. George and Martha had complete control over her life.

In Philadelphia, Ona met a thriving community of free Black Americans. She learned about organized efforts to abolish slavery and how individuals emancipated themselves by running away to states where slavery was abolished. The possibility was exciting, but self-emancipating was dangerous. George Washington whipped and physically punished the people he enslaved when they disobeyed him. Enslaved people who repeatedly caused problems on his plantation or tried to self-emancipate were sold to plantations in the Caribbean. In the Caribbean, the work was especially hard and the life expectancy for enslaved people was very short. In 1793, Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Law, making it easier for enslavers to reclaim enslaved people who escaped to freedom. Ona listened, learned, and waited for almost seven years until she took action to free herself.

In that time, Ona became Martha’s most trusted enslaved person. She was assigned to be Martha’s personal maid. It was Ona’s job to care for Martha’s wardrobe and perform any chores or errands she required. She accompanied Martha on social visits around the city. She also became someone Martha trusted with all her worries and cares. Being Martha’s maid meant Ona was constantly in the presence of her enslaver and had very little time for herself.

Ona’s life changed forever in March 1796 when Martha’s beloved grandchild, Eliza Custis, married Thomas Law. Martha was originally very unhappy with the marriage. Thomas was a former British government officer who had lived in India. He brought two half-Indian children to the marriage. Martha probably told Ona that she feared her new grandson-in-law was a man who took advantage of women of color.

Martha announced that she planned to give Ona to Eliza so Eliza would have the support of an outstanding maid while starting her new household. Once again, Ona had no choice in the matter. Eliza had a reputation as a demanding woman with a bad temper. Ona was not interested in being given to someone who would treat her poorly. Ona was probably also worried that Thomas would assault her based on Martha’s concerns. So Ona decided it was time to take her own freedom.

In Philadelphia, Ona met a thriving community of free Black Americans.

With the help of the free Black community of Philadelphia, Ona made her escape. She left the presidential mansion on May 21, 1796, when the Washingtons were eating dinner. It was too dangerous for her to stay in Philadelphia, so she soon boarded a ship headed to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. It is likely the captain of the ship was a known ally of the free Black community in Philadelphia because otherwise, someone would have reported seeing a Black woman traveling alone to the authorities.

When Ona arrived in Portsmouth, she was taken in by a free Black family who helped her find work as a domestic servant. The work was more difficult than what she had done as Martha’s maid, but she was paid for it and could make her own life. In January 1797, Ona married a free Black sailor named Jack Staines. They set up a home together, and soon after Ona gave birth to a baby girl. But both Ona and her daughter were still technically the property of the Washingtons, which was a constant threat to their safety and happiness.

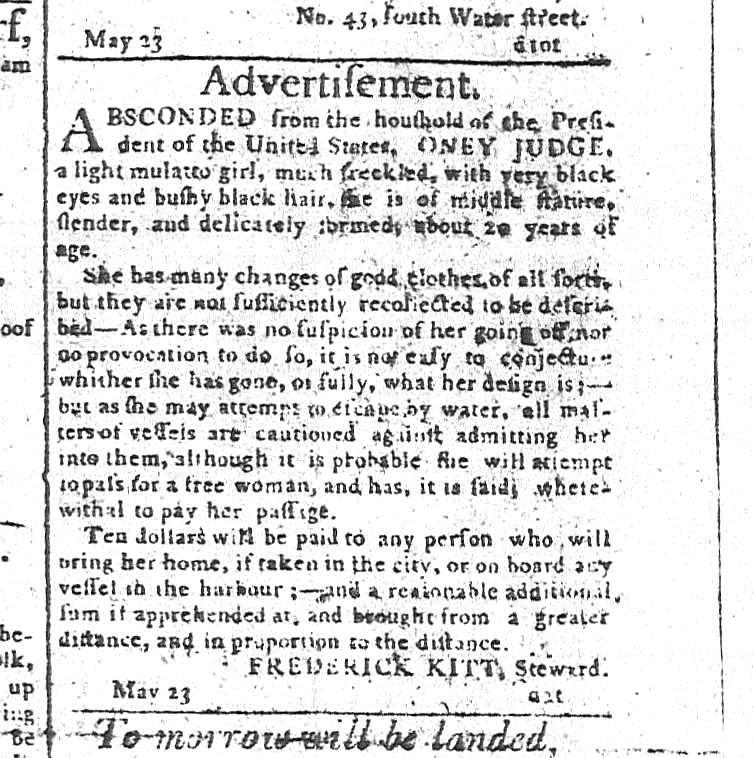

The Washingtons were furious when they discovered Ona had taken her own freedom. Two days after she left, they put an advertisement in the local paper offering a $10 reward for her return. The advertisement claimed she had no good reason for running away. This small detail reveals that George and Martha refused to acknowledge how oppressive enslavement was for the people they “owned.”

Word that an enslaved woman who had escaped from the President of the United States traveled quickly. By September, George knew Ona was living in Portsmouth. He could have used the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 to get her back, but he did not want to go to the courts because it would generate too much publicity. Instead, George used his presidential influence to make a government official in New Hampshire investigate the matter. The official met with Ona and tried to convince her to return to the Washingtons. Ona refused. George told the official to capture her and send her back, but the man declined.

In 1799, after he retired from the presidency, George sent his nephew to Portsmouth to try again. The nephew first tried to convince her to return. When she refused, he made a plan to kidnap her. He shared his plans with Senator John Langdon, who sent a message to Ona warning her to hide. The nephew was forced to return to Virginia.

George died in December of 1799, and no one ever again tried to recapture Ona. She gave birth to two more children and lived with her husband until his death in 1803. She moved in with friends and continued to work hard to support her children. Both of her daughters died in the 1830s, and there is no record of what became of her son. Towards the end of her life, Ona committed herself to work for her church. She also became involved in the growing abolitionist movement. In the 1840s, she gave two interviews to abolitionist newspapers detailing her life and escape from slavery, which is how so much of her story is known today.

Vocabulary

- abolish: To end.

- domestic servant: A person who does household work like laundry and cleaning.

- indentured servant: A person who’s under contract to work for another person for a definite period of time without pay, usually in exchange for transport to a new place or training.

- self-emancipation: To take one’s own freedom.

Discussion Questions

- What do the incidents of Ona’s enslavement teach us about the lives of enslaved people in the Federal period?

- What circumstances helped Ona in her bid for freedom? What do her experiences as a freewoman teach us about the challenges enslaved people who considered taking their freedom faced?

- How does Ona’s story change our perception of George and Martha Washington? Why is it important to know about these parts of their lives?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 3.10: Shaping a New Republic

- Invite students to read Ona’s accounts of her life. What does she have to say about the Washingtons? Why were these interviews published in the 1840s? Why is it important to read primary sources in addition to secondary sources when learning about a historical figure?

- Teach Ona Judge Staines’s life story in conjunction with lessons about Washington’s presidency, and ask students to reflect on how this story changes their perceptions of that time.

- To create a larger lesson about the lives of enslaved and free Black women in the Federal period, use any of the following: Abolition Loopholes, Life Story: Sukey, Free Black Americans, Life Story: Jarena Lee, and Life Story: Sally Hemings.

- To learn more about Black women’s role in the abolition movement, read The Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS