“The President Again”

James Callender, “The President Again,” September 1, 1802, The Recorder, or Lady’s and Gentleman’s Miscellany. Vol. 2, no. 61. Virginia Chronicle.com, Library of Virginia.

This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Sally Hemings was born in the year 1773. She was the daughter of an enslaved woman named Elizabeth Hemings and her white enslaver. Sally was three-quarters white and had very light skin. But under Virginia law, she inherited her mother’s enslaved status. Sally had five siblings who were also born enslaved. She also had five half-siblings who were born free because they were the children of her father and his white wives.

Sally’s father died the same year Sally was born. In his will, he left Sally, her mother, and her enslaved siblings to Sally’s half-sister Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. Martha moved the whole family to Monticello, the plantation owned by her husband Thomas Jefferson. When Martha died in 1782, Sally and her enslaved family became the property of Thomas Jefferson.

Like most enslaved people, Sally started working when she was very young. She took care of Thomas and Martha’s daughter Maria. Maria was only five years younger than Sally, and technically Sally was Maria’s aunt. Even still, she was expected to serve Maria and obey her every command. Sally was probably trained to do fine sewing and other advanced domestic arts so that when Maria grew up, she could be her lady’s maid.

When Sally was 14 years old, she traveled to Paris with Maria, where Thomas was serving as the U.S. Minister to France. While there, Sally worked as a lady’s maid for Maria and her older sister Martha. At some point during her two years in Paris, Thomas started a sexual relationship with Sally. Like her mother before her, Sally had no choice in submitting to a sexual relationship with her enslaver.

We have no way of knowing how Sally felt about her sexual relationship with Thomas. What we do know is that Sally was able to negotiate an extraordinary agreement with Thomas when he sent her back to Virginia in 1789. At the time, Sally was just 16 years old. Her son later reported that she was pregnant at this time, but no other record of this pregnancy exists. Sally lived in Paris long enough to know that according to French law, she could petition the government to stay in France and live as a free woman. She told Thomas that she would return to Virginia if he promised to free any children they had together when they reached adulthood. Thomas agreed, and Sally traveled back to Monticello. It is difficult to understand why Sally might have given up this chance at freedom, but her entire family still lived and worked at Monticello. It may be that she was unwilling to say goodbye to her family and community.

Sally had no choice in submitting to a sexual relationship with her enslaver.

Back at Monticello, Sally continued to work as Maria’s maid and companion. Her relationship with Thomas also continued. Between 1795 and 1808, Sally gave birth to six children, four of whom survived to adulthood. In accordance with their agreement, all four of Sally and Thomas’s children were enslaved while they were young. Her daughter, Harriet, was trained to spin thread in Thomas’ textile factory. Her three sons, Beverly, Madison, and Easton, were all trained as carpenters. It is possible that Thomas had his enslaved children trained in these trades so that they could support themselves when they were given their freedom. But there is no other evidence that Sally and her children were given special treatment at Monticello.

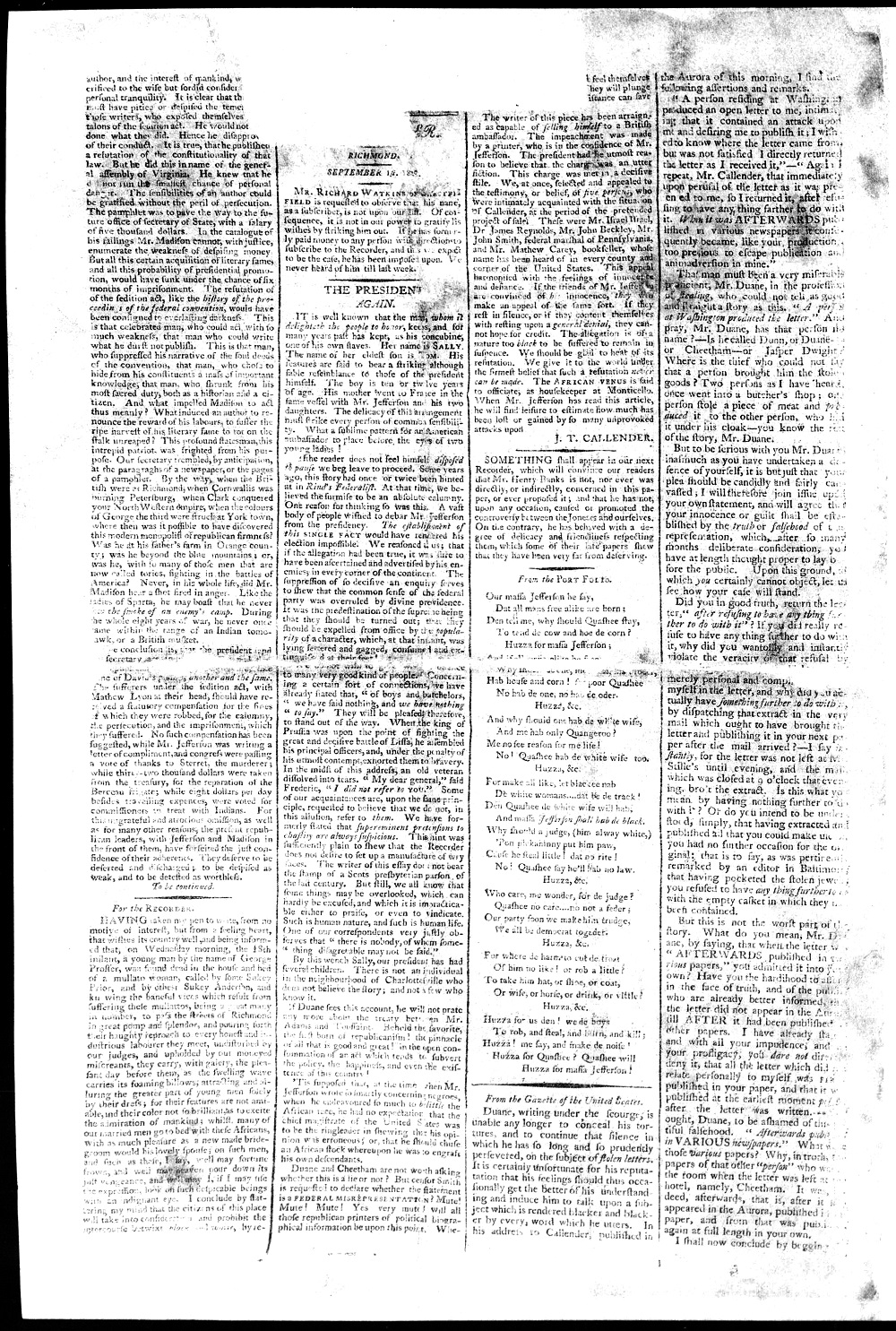

Sally’s relationship with Thomas did not go unnoticed. The community near Monticello and in the surrounding towns was aware, as were many of Thomas’s friends and political colleagues, of his relationship with Sally. In 1802, a scathing newspaper article informed the general public that Sally was Thomas’s concubine. However, sexual relationships between white men and enslaved women were very common in the early 1800s. Society was willing to ignore them if the man was discreet. Thomas Jefferson never acknowledged the rumors, publicly or privately, and so he was able to continue the relationship seemingly unaffected by the scandal.

In 1822, Thomas upheld his part of their agreement and allowed Sally’s two oldest children, Harriet and Beverly, to leave Monticello. All of Sally and Thomas’s children were seven-eighths white with light skin. Harriet and Beverly did not want to live with the stigma of being Black and formerly enslaved people. They started their new lives by moving to places where no one knew them, and they identified as white people. According to their brother Madison, neither was ever discovered.

When Thomas died in 1826, he freed Madison and Easton in his will, finally fulfilling the promise he had made to Sally nearly 30 years earlier. Sally was never officially emancipated. Instead, Thomas’s daughter Martha allowed her to leave the plantation with her younger sons. They moved to the nearby city of Charlottesville, Virginia. In 1830, all three self-identified as white for the U.S. Census. But three years later, during a special census, Sally identified as a free mulatto. These conflicting reports reveal that Sally had not settled on what racial identity she wanted to embrace as a free woman. Sally lived with her sons in Charlottesville until her death in 1835.

After their mother’s death, both Madison and Easton moved to Ohio. Both men made a point of publicizing that Thomas Jefferson was their father. In the 1850s, Easton changed his last name to Jefferson, to signify their familial relationship. In 1873, Madison gave an interview to an Ohio newspaper. In the interview, he asserted Jefferson was his father and gave details about his family’s life in Monticello. Most of what historians know about Sally’s life comes from this interview.

For decades, historians dismissed the story told by Sally Hemings’s descendants. They refused to believe that a man who had written so beautifully about the ideals of the new nation was capable of sexually exploiting a woman he owned. But Sally’s descendants never stopped telling her story. They wanted their ties to Thomas acknowledged and the country to reckon with the horrible hypocrisy of slavery in the founding era. In 1998, a DNA test showed that descendants of Easton and descendants of Thomas’s white children shared a common Jefferson ancestor. Some people still try to argue that it was Thomas’s brother or another close relative who fathered Sally’s children. But the most logical explanation is that Thomas was the father. Today, Sally’s story is included as an important chapter in Thomas Jefferson’s life. It reminds us of the culture of exploitation and cruelty within the practice of slavery in the new nation.

Vocabulary

- apologist: A person who defends someone controversial.

- concubine: The 18th-century word for woman who has an ongoing sexual relationship with a man outside of marriage.

- descendants: People who are related to other people from the past.

- discreet: Not sharing private information.

- emancipated: Freed.

- Minister to France: Early name for the U.S. ambassador to France.

- textile: Cloth or woven fabric.

- will: A legal document where a person describes how they want their belongings distributed after their death.

Discussion Questions

- What does Sally Hemings’s story teach us about the lives of enslaved women in the Federal period?

- How did Sally exert agency in her life? What were the outcomes of her choices?

- The way historians talk about Sally Hemings has changed dramatically over the last 200 years. What does this teach us about the way history is recorded and retold?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 4.2: The Rise of Political Parties and the Era of Jefferson

- Teach Sally Hemings’s life story in conjunction with lessons about Thomas Jefferson’s career and presidency, and ask students to reflect on how this story changes their perceptions.

- After reading the life story, ask the students to read and analyze the 1802 newspaper article that exposed Sally’s relationship with Thomas. How does the writer characterize Sally? How does he characterize Thomas? What is the writer trying to accomplish? Then ask the students to rewrite the article based on what they’ve learned about Sally Hemings’s life. What do they think readers should know?

- For a lesson that takes a closer look at the experiences of people enslaved by early presidents, teach this life story together with Life Story: Oney Judge and Life Story: Sukey. Be sure to consider how each woman exerted her agency and shaped her life within the limitations of enslavement.

- To learn more about Federal period attitudes towards women who had sex outside of marriage, see Seduction Suits.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS