Document Text |

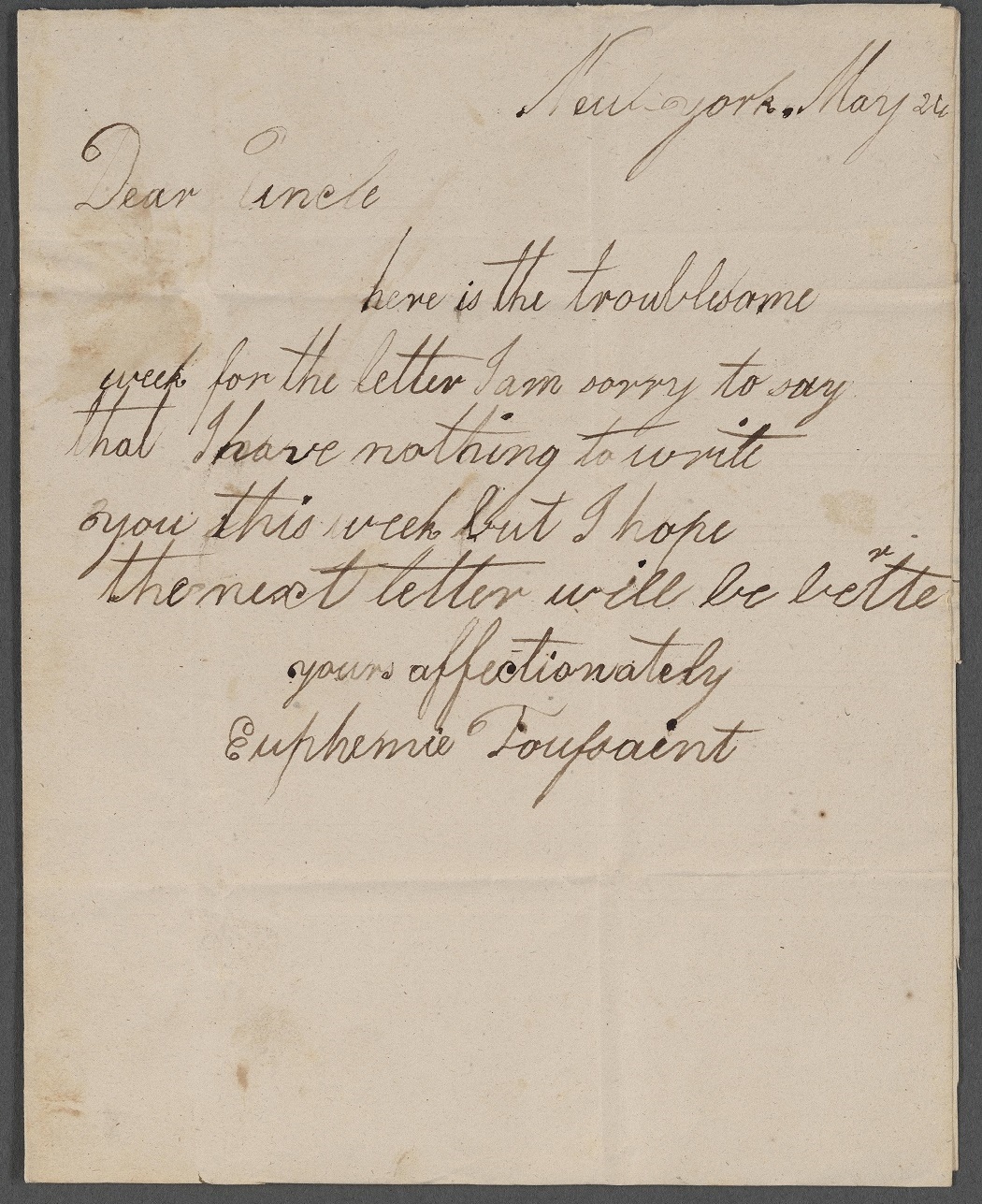

| New-York, May 26

Dear Uncle, Here is the troublesome week for the letter. I am sorry to say that I have nothing to write you this week but I hope the next letter will be better. Yours affectionately, Euphemie Toussaint |

“Euphemia Toussaint to Pierre Toussaint,” May 26, 18??. Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

Document Text |

Summary |

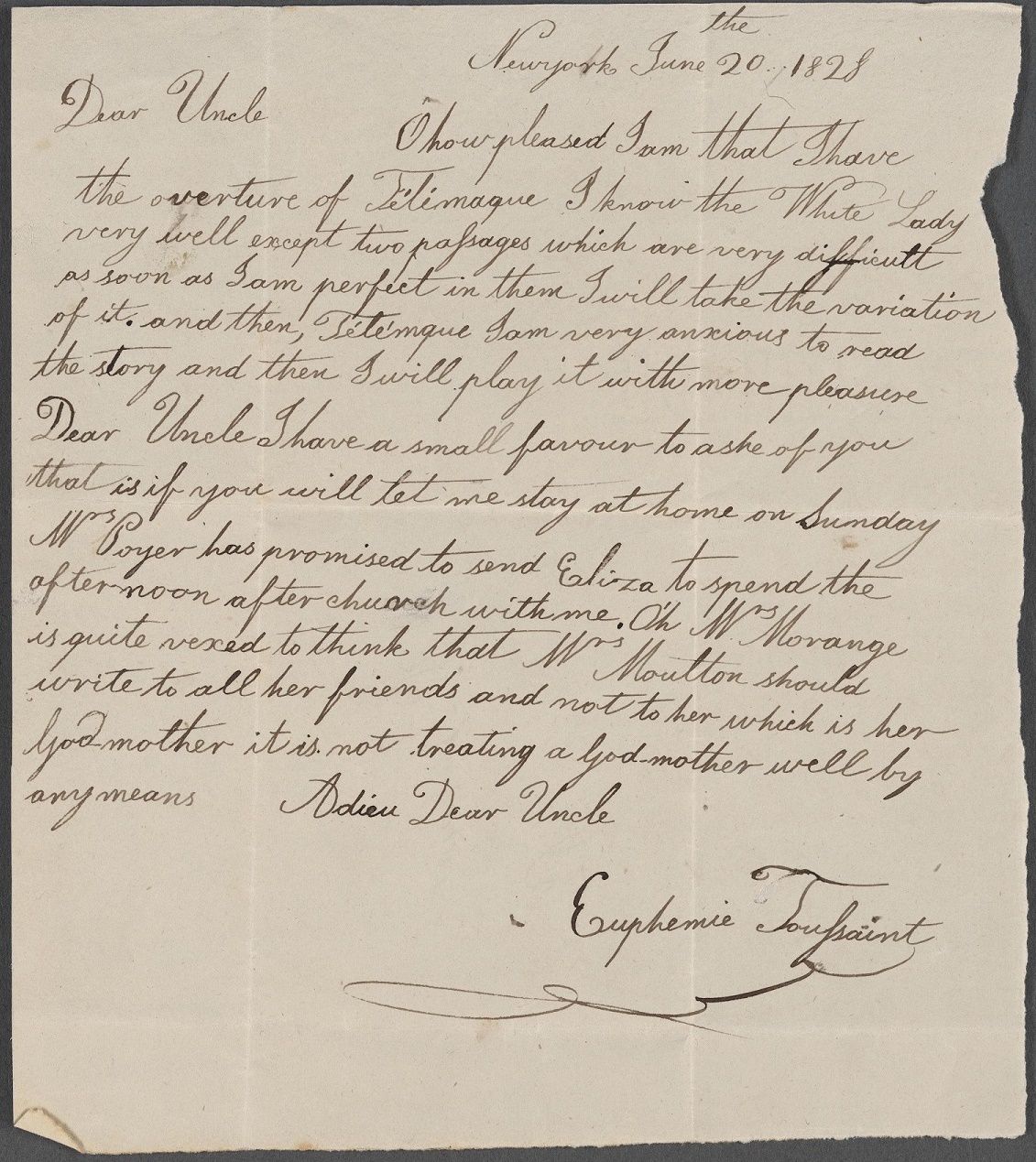

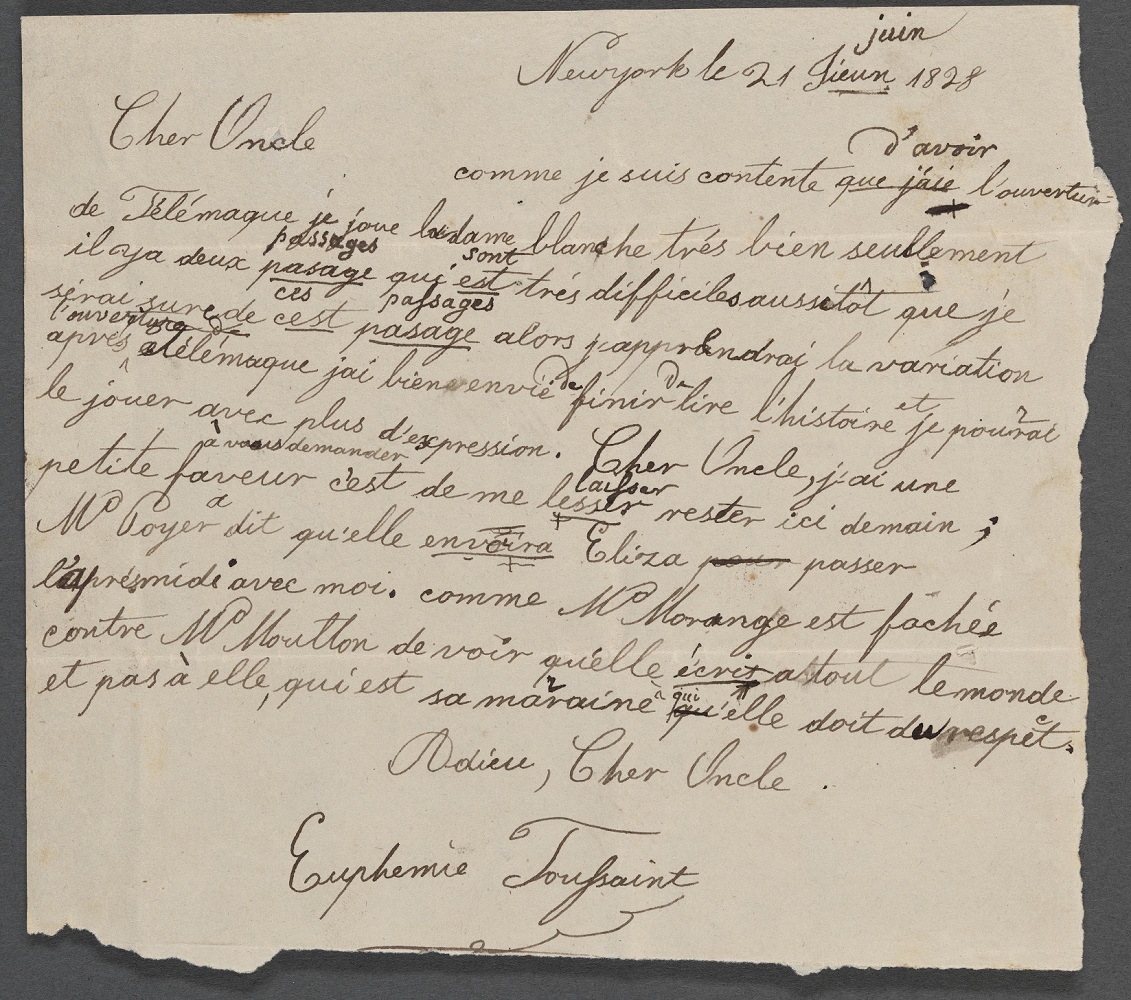

| New York June the 20, 1828

Dear Uncle, |

|

| Oh how pleased I am that I have the overture of Télémaque. I know the White Lady very well except two passages which are very difficult . As soon as I am perfect in them I will take the variation of its and then, Télémaque. I am very anxious to read the story and then I will play it with more pleasure. | I am so happy to have a new piece of music to learn. I have a little more to learn in my current piece and then I can start the new one. I’m going to read the story of the piece so I enjoy it more. |

| Dear Uncle, I have a small favor to ask of you. That is if you will let me stay at home on Sunday. Mrs. Boyer has promised to send Eliza to spend the afternoon after church with me. Oh Mrs. Morange is quite vexed to think that Mrs. Moulton should write to all her friends and not to her which is her god mother. It is not treating a god mother well by any means.

Adieu Dear Uncle, Euphemie Toussaint |

I have a favor to ask. Can I stay home on Sunday? My friend is going to come over. Mrs. Morange is very mad that her goddaughter did not write her a letter. I think she is right. |

“Euphemia Toussaint to Pierre Toussaint,” June 20, 1828. Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

Background

Throughout the Federal period, free Black Americans were subject to discriminatory laws and oppressive social restrictions that prevented them from achieving equity with white Americans. Even so, they persisted in asserting their dignity. Free Black Americans came together all over the United States to form communities to support one another. They donated resources to build Black churches and schools and established businesses to serve their communities when white businesses would not. They were also the backbone of the national grassroots movement to abolish slavery in the U.S.

About the Image

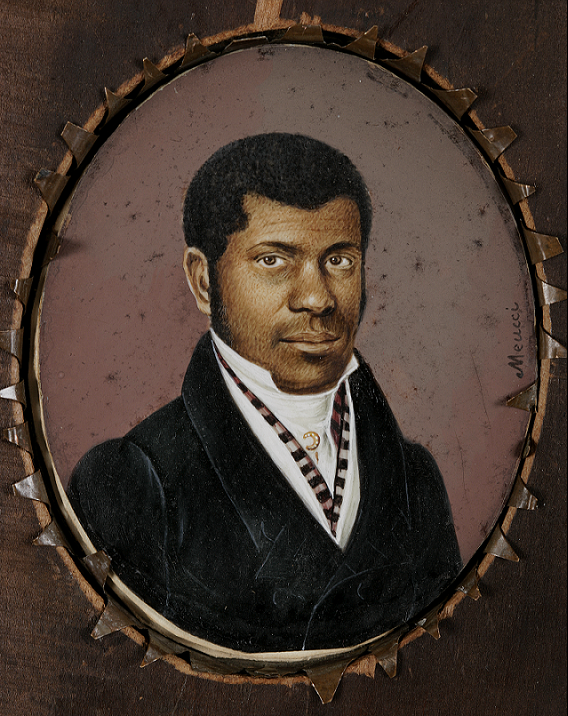

These portraits depict the three members of the Toussaint family, one of the most successful and generous free Black families in New York City during the Federal period. Husband Pierre Toussaint began his life enslaved on a plantation in Haiti and was brought to New York by his enslavers in 1787. He was trained as a hairdresser and, through hard work, became a huge success. Pierre voluntarily used his earnings to support his enslavers. He was granted his freedom when the last member of the family passed away in 1807.

Pierre’s hairdressing business continued to thrive. In 1811, he used his earnings to purchase the freedom of Juliette Noel, the woman he loved. The two married and adopted and freed Pierre’s niece, Euphemia. The Toussaint family opened their home to Black orphans, established a credit union and employment agency for Black workers, and funded the building of Old Saint Patrick’s Cathedral.

These portraits, painted on ivory, are more than just family mementos. They are important visual symbols of the success of free Black Americans at a time when racial oppression was the norm. Miniatures like these were expensive, so their existence is a testament to the financial achievements of the Toussaint family. The family is all dressed in the latest fashions, which assert both their personal dignity and their equality with white Americans. Juliette wears a tignon, a fashionable Federal period headdress that has its roots in Black women’s resistance to oppressive sumptuary laws.

Pierre and Juliette hired tutors to teach Euphemia. Every week, Euphemia wrote a letter to Pierre to show him how much she had learned. She often wrote the same letter in both French and English. It is clear from these examples that Euphemia found French more challenging and sometimes found the task boring. Euphemia’s letters are rare windows into the daily life of a free Black girl during the Federal period.

Vocabulary

- credit union: A financial institution similar to a bank but owned by the members who contribute to it.

- Federal period: The early years of the United States, usually defined as 1790–1830.

- tignon: A cloth wrapping that covered the hair. Free Black women in colonial Louisiana were required to wear a tignon beginning in 1786.

Discussion Questions

- What do the details in these portraits tell us about the Toussaint family?

- Why are portraits of Black Americans in the Federal period rare? What does the existence of these portraits tell us about the Toussaint family

- What do Euphemia’s letters reveal about her daily life?

- Why is it important to know the history of free Black Americans?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 4.12 African Americans in the Early Republic

- Combine Juliette Toussaint’s portrait with the following resources for a lesson about the ways women used fashion to project political and social ideologies in the Federal period: Fashion and Politics, Life Story: Dolley Madison, and Fashionable Rebellion.

- To learn more about the education Euphemia Toussaint received in the Toussaint household, see Educating American Women.

- Use any of the following to learn more about the lives of enslaved and free Black Americans in the Federal period: Abolition Loopholes, Life Story: Oney Judge, Life Story: Sukey, Educating American Women, Life Story: Jarena Lee, Life Story: Sally Hemings, and Life Story: Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley.

- Pierre Toussaint has been nominated for Catholic sainthood, but Juliette has received no such honor. Ask students to learn more about Juliette’s life and work by reading Pierre Toussaint’s memoir and suggest a way to honor her contributions to Black history.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP; AMERICAN CULTURE