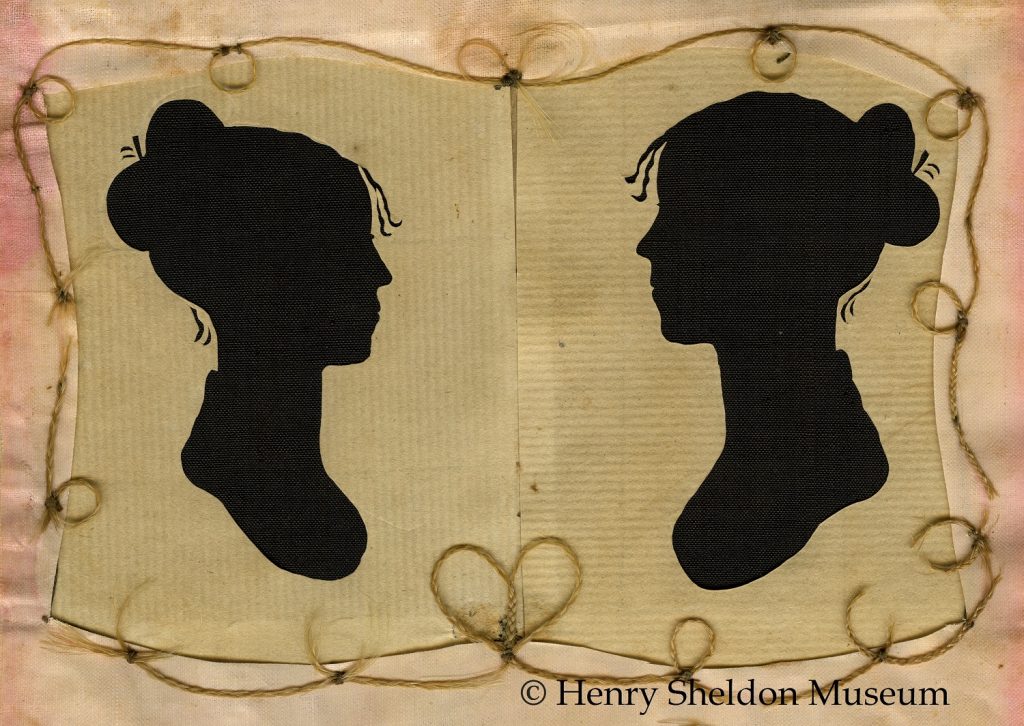

Double silhouette of Sylvia Drake and Charity Bryant with braided human hair.

This video was created by the New-York Historical Society Teen Leaders in collaboration with the Untold project.

Charity Bryant was born in North Bridgewater, Massachusetts, on May 22, 1777. Her mother died only a month after she was born, leaving behind ten children and a husband. Charity’s father remarried, but his new wife was not fond of her stepchildren. She and Charity had a particularly tense relationship. Charity hated housework, preferring to spend her time studying and writing. She also did not follow the rules that dictated women’s behavior at the time. Many people who knew Charity noted that she spoke and walked like a man. She also refused to get married, something that left her family anxious about her future.

In 1797, Charity left home to become a teacher. She did not particularly like teaching, but it was one of the only respectable ways she could earn a living and still have time to study and write. Teaching also allowed her to meet other young women who shared her interests. Charity threw herself into this new community of like-minded women and formed very close relationships with many fellow teachers. Some of the relationships may have developed into something more than friendship.

Studying historical same-sex relationships is challenging. For the majority of human history, such relationships have been illegal. This doesn’t mean that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people did not exist. It just means that people who loved people of the same gender had to be careful to hide their relationships. There is evidence that Charity and her particular friends routinely destroyed anything that might arouse suspicion concerning the nature of their relationship. But there are also lots of clues that these relationships were both romantic and sexual in the records that survive. For example, Charity’s friend Lydia wrote about how she hoped they would be able to share a bed for the rest of their lives. Maybe she just really liked sleepovers, but it seems more likely that something more was going on.

Perhaps the most concrete evidence that these relationships were more than friendships is the way the women’s families and communities responded to them. For 10 years, Charity was driven from town to town by the vicious rumors that circulated about her relationships with women. The primary concern was that Charity had no intention to get married, and the women who became her “friends” did not want to marry either. She was labeled a corrupting influence. The shame she experienced made her severely ill. Even the love and support of her favorite brother and sister could not keep her safe from the harmful judgments of her community. Finally, in the spring of 1807, she decided to escape the pressure by accepting an invitation to visit her friends Polly and Asaph Hayward in the new settlement of Weybridge, Vermont.

Charity’s life changed forever when she met Polly’s younger sister Sylvia Drake. Like Charity, Sylvia had lived a hard life. She was born on October 31, 1784, the youngest of eight children. Her father went bankrupt when she was only four years old, and her siblings were all sent away to work for a living. Sylvia and her mother eventually followed her older brother to Weybridge, where the small community and abundant land gave them a chance to start over. Sylvia wanted to go to school, but her family could not afford it. She worked at home instead. Men far outnumbered women in Weybridge. Sylvia had many offers of marriage before she met Charity, but she turned them all down. This upset her mother and siblings, who feared that Sylvia would become a burden on the family as she got older.

Charity started working as a tailor soon after she arrived in Weybridge. This indicates that she was planning to turn her visit into a long-term stay. This may be because she fell in love with Sylvia. There was so much work that Charity was soon able to rent a place to live. She invited Sylvia to move in with her, claiming she needed Sylvia to help run her business. Sylvia’s family approved the plan, relieved that she would have a way to support herself. Sylvia moved in with Charity on July 3, 1807. For the rest of their lives, Charity and Sylvia celebrated July 3 as the anniversary of their lifelong commitment to each other. They did not spend a night apart for the next 44 years.

Charity and Sylvia were recognized as a married couple in Weybridge and eventually celebrated as models of lifelong companionship.

Life was not easy for Charity and Sylvia. On top of all the traditional women’s work necessary to keep a home running, they had to work long hours to make enough money from their tailoring business. Sylvia’s mother and some of her siblings soon realized that the women were more than work colleagues. Some refused to visit their home for years. Both women also struggled with the fact that their love for one another was condemned by the church they attended.

Over time, their love and persistence paid off. They were recognized as a married couple in Weybridge and eventually celebrated as models of lifelong companionship. They were able to build their own home and expand it over time. They became beloved aunts to the dozens of nieces and nephews their siblings raised. They were also respected mentors and employers for local women who wanted to enter the tailoring trade. Sylvia even ran the local Sunday school for many years. In 1843, their relationship was immortalized by Charity’s nephew William Cullen Bryant, who published a beautiful tribute to them in the New-York Evening Post.

Historians attribute their success to two important factors. The first is that Charity and Sylvia lived in a new settlement where every member contributed to the success of the community. The people of Weybridge may have been willing to overlook their unusual relationship because both women contributed to the town’s success. Second, Charity and Sylvia were careful to keep their relationship a very open secret. There was only one bed in the home they occupied, but they never spoke openly about the nature of their relationship. This allowed their family, friends, and neighbors to conveniently ignore the exact nature of their relationship and instead focus on everything they contributed.

Charity passed away in 1851. The community at Weybridge mourned her passing, not just because she was a pillar of the community, but because they knew what her loss meant for Sylvia. When Sylvia died 17 years later, her nieces and nephews ensured that she was buried next to Charity and that both women were commemorated on a single gravestone. That way, they could spend the rest of eternity united as they were in life.

Vocabulary

- bisexual: A person who is sexually attracted to both men and women.

- gay: A man who is sexually attracted to men.

- lesbian: A woman who is sexually attracted to women.

- tailor: A person who makes clothing

Discussion Questions

- What challenges did Charity and Sylvia face in their lifetimes?

- What attributed to Charity and Sylvia’s acceptance in the town of Weybridge, Vermont?

- Why is it important to research LGBTQ+ histories and include them in historical narratives?

Suggested Activities

- When the state of Vermont was debating whether to legalize same-sex marriage, supporters cited Charity and Sylvia as evidence that same-sex marriage has always been a part of the fabric of the state. Ask students to write a reflection on how Charity and Sylvia’s story can be a powerful tool for advancing same-sex marriage equality.

- To help students understand the social and legal limitations that governed Charity and Sylvia’s lives, see Republican Motherhood and Reaffirming Coverture.

- To learn more about how life in new settlements gave women freedom to defy social and legal expectations, see White Settler Women and Settling Texas.

Themes

DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY; AMERICAN CULTURE